Revisiting ‘Satellite Dreaming’

A personal account of the process of making this website, by Tony Dowmunt

‘…there’s a wonderful quote […] attributed to a collective Aboriginal voice […] in the 1970s […] It says if you have come over here to help me, you’re wasting your time, but if you have come here because your liberation is bound up with mine, then we can work together.’ (Sam Burch, in Burch et al 2020, 119)

The development of this website project, and of the original TV programme that prompted it, is partly a personal story – one in which I recognise and acknowledge how my own 'liberation' (as a UK based media activist and academic) 'is bound up with' my involvement with Australian Indigenous media.

I first became aware of this area of work in the mid-1980s. I had been engaged for the previous decade with activist and community media projects in London, UK. We attempted to work within and alongside groups of people whom we identified at the time as being excluded from mainstream media - working class, youth, Black, Gay and Lesbian and Disabled people. We worked to enable them to be able to represent themselves, in media they were in control of [1]. These projects, and others like them throughout the UK (together with the community and identity politics that sustained them), had begun to lose public funding and support by the middle of the decade, declining further during the ascendancy of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in the UK. The Falklands/Malvinas war in 1982, the defeat of the Miners’ Strike in 1984, and the abolition of the (mostly Labour) Metropolitan Councils, all contributed to a growing feeling of demoralisation and defeat in our sector, and many others on the Left.

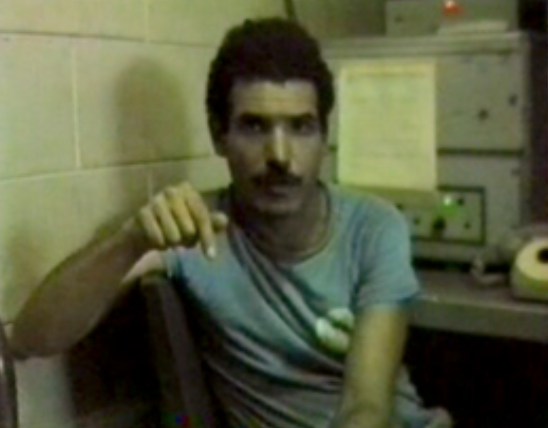

Still from Satellite Dreaming

It was in this atmosphere that I heard of an inspiring development on the other side of the world: the (eventually successful) campaign by the indigenous media organisation CAAMA to win the television license for the AUSSAT Central Australian footprint, against considerable mainstream opposition [2]. This could enable Indigenous communities to control how television was used and seen within this footprint: an apparent victory against European ‘cultural imperialism’, in favour of locally controlled ‘cultural maintenance’. This fascinated me because of the way it chimed with the ideas behind our community media projects, and our work with groups who we identified as being excluded from mainstream media. The difference was that in Alice Springs it sounded as though the ‘excluded’ had won an enormous amount of power: David had slain the Goliath of mainstream ‘whitefella’ media.

In 1986 I was visiting Australia with my partner at the time, who was Australian and had family in Melbourne. I persuaded her to drive with me for the 1400 miles (2256 km) to Alice Springs, the last 200 km or so on dirt roads, as the Stuart Highway hadn’t yet been paved all the way to Alice. I wanted to meet people from CAAMA to find out more about the (by that time, victorious) AUSSAT campaign, and I spent a fascinating afternoon in CAAMA’s offices, talking with Philip Batty.

By the end of the 1980s and back in the UK, my focus had shifted away from working in community-based media. With two filmmaker friends, I set up a small production company (APT Film & Television) to make programmes commissioned by Channel 4. Some of our work was for the Independent Film & Video Department, which, in the words of Rod Stoneman – a Commissioning Editor in the Department – “took risks and developed programming that gave voice to the marginalised” (Stoneman 2020). We made a programme for the Channel in 1989 called Remote Control, which argued the case for community media and increased access in the context of broadcasting legislation in the UK. Then, in the early 1990s, we worked on a season of programmes called Channels of Resistance for which, as well as co-producing Satellite Dreaming, we made Tactical TV, looking at a range international experiments in community-based and oppositional TV and video.

When we were first commissioned to work on the Channels of Resistance series, I had been keen to have a programme about indigenous video and TV in Australia in it, largely because of my conversation with Philip Batty in 1986. Channel 4 agreed and we contacted CAAMA and asked them to collaborate with us. We brought around half of the budget from Channel 4 to the project, and Ivo Burum, the Executive producer of CAAMA Productions at the time, raised the rest.

I travelled to Alice Springs early in 1991 to co-produce the programme with Ivo. I had submitted early, rough treatments of the programme to CAAMA, but most of the work of fleshing out the content and schedule had been done by the time I arrived In Alice Springs. So, my role was relatively minor during the shoot – principally involving discussions with Ivo and Nicolas Lee (the editor) during the production and early stages of the edit, as well as conducting many of the interviews during the shoot. I was happy with this limited role, because, as a ‘whitefella’ from the UK, my knowledge of Australia as a whole, and my experience of Alice and the bush were limited to my brief visit in 1986.

Francis Kelly and myself (at the back) in Yuendumu, 1991

So, I had enough time in those two months or so in early 1991, to savour a range of experiences which were a fascinating mixture of the familiar and the strange. To give three, small examples: I knew something about the routines and conventions of television production from my work up until then, but was completely unused to conducting them in temperatures of over 45 Celsius; I’d been in many video editing suites, but none up to then with spiders that looked to me as big as tarantulas crawling around the air-conditioning machines; and on the shoot in Yuendumu I found myself comparing notes with Francis Jupurrurla Kelly on the early black and white video recorders (portapaks) we had both worked with earlier in our working lives: me in South London, him in remote communities in the Tanami Desert.

But what struck me most forcibly were my encounters in the remoter communities with a culture wholly different from my own. When we were working with EVTV I was walking through the settlement with Neil Turner, quenching my thirst in the searing heat with a can of Fanta orange. We were approached by an older man who clearly knew Neil well. I was puzzled when Neil introduced me to him as ‘Kunmanara’ (not ‘Tony’), and more so when the old man - without asking – reached for my Fanta and drank half of it down. Neil later explained that he was unable to use my name ‘Tony’ because it was also the name of a recently deceased person in the community, so taboo; and, because I was with him (Neil) I was automatically in a kin relationship with the older man (as Neil was), and he was therefore fully entitled to share my drink without explanation.

We spent two or three days shooting the Kuruala trip, which deeply affected many of us involved in the production. We were forced to go at the pace of the ceremony, and so time slowed down, at least in comparison with the speed at which films are ‘normally’ shot (time being money on conventional productions, of course). We waited for something to happen, and eventually it did. Neil Turner remembers it as the ‘magic moment on the Satellite Dreaming shoot - everyone having come together […] to revive that song from Ooldea, and perform the dance for it’; and Topsy Walter described in Satellite Dreaming how:

Topsy Walter in Satellite Dreaming

'We went far away to Kuruala, the other side of Pipalyatjara. Many women were sitting together, singing at that beautiful place. We were performing Nyiru and the Seven Sisters. Men, women and children were singing together. Men were stamping their feet in an absolutely beautiful dance, and we ignorant ones were listening to that song. Others that knew it were singing the song – the men were stamping really beautifully…'

Ivo Burum remembered the event too :

‘…then the men did this dance and the ground shook. It was a dance that hadn’t been done for 30 years and we could feel the ground shaking. And in an instant, really, in an instant this whole Indigenous connection to this world, to this ground became apparent. It’s stuff that we can’t really even rationalize…’

Nicolas Lee, who wasn’t on the shoot - so experienced it only when he was editing the footage back in Alice Springs - felt it was ‘spine tingling. It would have been more so to be there. But even in the edit suite it was spine tingling.’

We had come all the way to Kuruala originally to shoot a sequence about the Seven Sisters songline. The Ooldea song was an unexpected bonus, and it’s still unclear how it was re-discovered by the participants.

Singing the Ooldea song at Kuruala - still from Satellite Dreaming

Ooldea is hundreds of kilometres southeast of Kuruala, on the other side of the desert where the British tested nuclear bombs in the 1950s at Maralinga (Tynan 2016). Somehow the participants remembered the song and began singing. In 2020 Neil Turner told me that it was:

‘as much a mystery to me as it was to you, perhaps as to where it sprang from and how that came about. But… they told me that, you know, that hadn't been performed for 40 years. […] for this old song to have been kind of revitalised just by people being together on a shoot…’

I wondered at the time whether the customary oral transmission of the song (traditionally communicated by people travelling overland) had been interrupted by the contamination and the ‘terrible harms caused to the Indigenous peoples of the Maralinga lands’ (Tynan 2016: 199) by the nuclear tests. I had the (probably naïve) hope that our filming had in some way contributed to this cultural revitalisation across the poisoned landscape.

In any case for me, sitting on the ground with the singers, feeling the reverberating thuds of the sticks as they beat out the rhythm, was a deeply memorable experience.

The Kuruala sequence, positioned as it is as the climax of the film, was also one of the factors that shaped Satellite Dreaming’s overall points of view and underlying assumptions. With the benefit of hindsight I think these can be categorised under three main headings:

A tendency to favour work in the centre of Australia, rather than in the coastal cities, perhaps inevitably given CAAMA’s being based in Alice Springs.

A particular validation of work in the remoter communities in the centre (especially the Warlpiri Media Association (WMA) and EVTV). My opinion at the time was ‘the further from cities and towns the work is, the more the initiative remains in Aboriginal hands […] In modern media economies, the wider your audience reach, the greater the constraints on production’ (Dowmunt 1991: 45)

Allied to the point about 'initiative' above, a focus on the importance of the idea and practice of ‘self-determination’ in relation to indigenous media work.

I’ll return to the implications of the first two of these later in this essay, but for now I’ll just say a little more about the last point. In the early 1990s the policy of self-determination was still in the ascendant, so in 1993 Philip Batty and Tom O’Regan were able to conclude:

For many Aboriginal broadcasters, self-determination in Aboriginal television is an important component of the broader struggle for the power and right to determine Aboriginal cultural, political and economic futures.

With political and legal recognition inching towards formal recognition of the special claims of indigenous people, and with greater acceptance of Aboriginal economic and cultural self-determination amongst the broader population, the possibility of a number of kinds of Aboriginal autonomy within an overarching Australian territorial state is an increasing possibility. Aboriginal television is inevitably moving in this direction too. (Batty & O’Regan 1993: 192)

The apparent inevitability of this ‘greater acceptance of Aboriginal […] self determination’ at the time was one (perhaps the major) cultural and political factor from the early 1990s that has been brought into question in subsequent decades - not least by Philip Batty himself, who writes about it in his essay on this site.

After the Channels of Resistance series went out (in 1993 in the UK), powerful memories of making Satellite Dreaming remained with me, and I kept in touch as much as I could with what was happening in Australia.

In 1997 I wrote an article (Heat from a Small Fire) that revealed my continuing loyalty to the assumptions outlined above. In it I described an encounter with a feature film production in Alice that I and some people from EVTV had while we were editing Satellite Dreaming, and the article is an expression of my identification with ‘small’, autonomous local media over its ‘mass’ alternatives.

During this period too I was teaching on an MA in ‘Video for Development’ in the UK, and relying heavily on the work of EVTV, WMA in Yuendumu and the writings of Eric Michaels, as exemplars of progressive, ‘bottom-up’, democratic media use – instances of ‘resistance’ to what I saw as the cultural uniformity and colonising tendencies of mass media, a clear binary and oppositional relationship between mainstream its local alternatives.

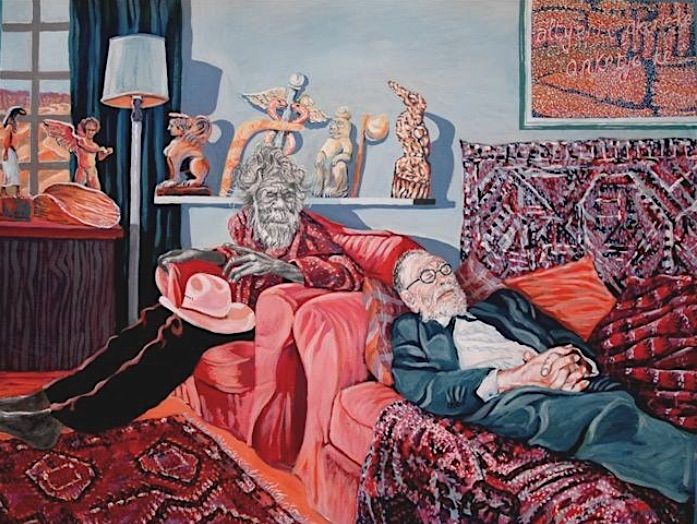

Eric Michaels, 1986

However, in the following years I was also made increasingly aware of the limitations of the binary assumptions behind this ‘resistance’ model, as well as of many forceful critiques of the work of Eric Michaels. This is a process I wrote about after the first few years of research for this site (in Will it Harm the Sheep? Dowmunt 2015), so I won’t go into much detail here, except to acknowledge my particular debt to the writings I cite in that essay by Philip Batty, Melinda Hinkson and Jennifer Deger.

In the early 2000s I was also one of the editors of a book about ‘alternative media’ (Coyer, Dowmunt & Fountain 2007), set principally in the UK. Here I was influenced by the work of the Colombian alternative media activist and academic, Clemencia Rodriguez, who argued against the

rigid categories of power and binary conceptions of domination and subordination that elude the fluidity and complexity of alternative media as a social, political, and cultural phenomenon. It’s like trying to capture the beauty of a dancer’s movements with one photograph. (Rodriguez 2001: 3-4).

This growing awareness of the restrictiveness of binaries in relation to both alternative and indigenous media was a major part of my wanting to return to the work we had explored in Satellite Dreaming. I began devising the Revisited project, both to satisfy my own curiosity, and to challenge my previous assumptions. I planned to revisit the people who had been involved in the programme, in front of and behind the camera, and to seek out others currently concerned with the issues we had dealt with. My aim was to give them all an opportunity to talk back to, disagree with, or add to the original programme.

In 2011 I began the research process by visiting Alice Springs, for the first time since co-producing Satellite Dreaming with CAAMA in 1991, a twenty-year time span. I called in at CAAMA’s office – now a smart building in the centre of town, rather than the collection of huts in the Gap that we worked in in 1991.

1991

2011

The CAAMA lobby, 2011

When I walked in the door I was startled to see and hear – on the large TV that dominated the lobby – a sequence from Satellite Dreaming.

I learned from the people I met at CAAMA that the programme was still widely shown and used, and that they had thought about up-dating or re-making it. CAAMA Productions and myself agreed that, during my stay in 2011, I would record some interviews in and around Alice Springs, and in the coastal cities. We contacted many people who had had roles in Satellite Dreaming both in front of and behind the camera – as well as others who would be able to comment on the issues raised by the programme.

I was interested in doing this work as a research project (I was on sabbatical from my job at Goldsmiths at the time), and CAAMA saw the project as generating pilot material for a potential re-make of the original programme.

In the end the re-make never happened: CAAMA, though they generated some interest in the idea, were unable to recruit an indigenous director, or raise enough money to get it made. I carried on filming interviews, and slowly formed the idea of building a website based on them. I’d acquired some experience of this way of working through collaborating on a site about activist video in London and the South East of the UK. It seemed an ideal way of presenting visual material, but as importantly, to explore issues ‘polyvocally’, enabling multiple and diverse voices to comment and contribute. This was important to me both because I was a white European from the other side of the globe, and because there are of course a range of different and sometimes conflicting viewpoints in the Australian indigenous media sector itself. A website – differently to more linear and heavily authored media – gives users more of an opportunity to navigate their way through a history or a debate, being able to some extent to structure their own experience of the material, albeit by using the links provided for them.

As I talked to people, I quickly came to understand that the situation in 2011 differed in many ways from the one I had encountered 20 years before. As I mentioned above, there had been a substantial contraction of the policies of ‘self-determination’ in relation to Aboriginal populations, compounded by the Northern Territory ‘Intervention’, which I also discussed in Will it Harm the Sheep?. In addition, the interests of indigenous media workers in remote communities and those in more urban and coastal areas had become more polarised in the early 2000s. Marcia Langton had made the point back in 1993 that ‘Aboriginal cultures are extremely diverse and pluralistic’, and pointed to ‘two broad regions’, the first being ‘‘settled’ Australia, stretching from Cairns round to Perth in a broad arc’ (Langton 1993:11) and the second ‘‘remote’ Australia where most of the tradition-oriented Aboriginal cultures are located’, emphasising how ‘these two regions are quite different. They are grounded in different cultural bases histories and socio-political conditions’ (12).

These differences became bitter divisions in the period 2005-10 when NITV (National Indigenous Television) was set up, a period one of the people I visited in 2011 described as ‘less Satellite Dreaming, more Satellite shitstorm’. The conflict, as I see it now, was caused in part by the way in which scarcity of resources forced a confrontation between NITV and the remote media sector represented by ICTV (Indigenous Community Television). Some of the flavour of the conflict from ICTV’s point of view can be gleaned from an article by Frank Rijavec, who described the way NITV was being set up as ‘careless, crude and unnecessary’ (Rijavec 2010). I’ll return to this issue and its more recent developments in the following discussion of the Revisited research interviews. This discussion will form the basis of the rest of this essay.

My first choice of interviewees for the site was based on wanting to speak to as many people as possible who had a direct involvement with Satellite Dreaming, in front of or behind the camera: those who were still alive, and whom I was able to contact and were willing to be interviewed. 18 out of a total of 24 were in this category. The remaining 6 were people who I judged had an important perspective on issues raised in Satellite Dreaming and the subsequent history of indigenous media.

The fact that the COVID Pandemic broke out a few months before my final projected research trip to Australia to do the final 11 or so interviews, had a couple of implications: I was forced to do many of the interviews remotely (zooming or skyping my questions in and employing local crews to shoot them), and in a few cases (Freda Glynn, Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, Lester Bostock and Pantjiti Tjiyangu) I decided to use interview material from other films, which, as a bonus, were almost certainly more revealing and intimate than I would have been able to achieve if I’d conducted them myself. The interviews were also recorded over a long time span - at least a decade (2011-2021).

All these factors meant that the interviews featured on the site are very different from each other. However, in all the ones I conducted myself, though they were influenced and structured by the interests and experience of the interviewees themselves, I also tried as well to cover two particular topics: their memories and impressions of Satellite Dreaming, and how they saw changes and developments in the field since 1991, from their particular points of view.

I learned a lot from the interviews about the impacts that Satellite Dreaming had had, both on participants in the film – in front of and behind the camera - and on others who hadn’t been involved in making the programme.

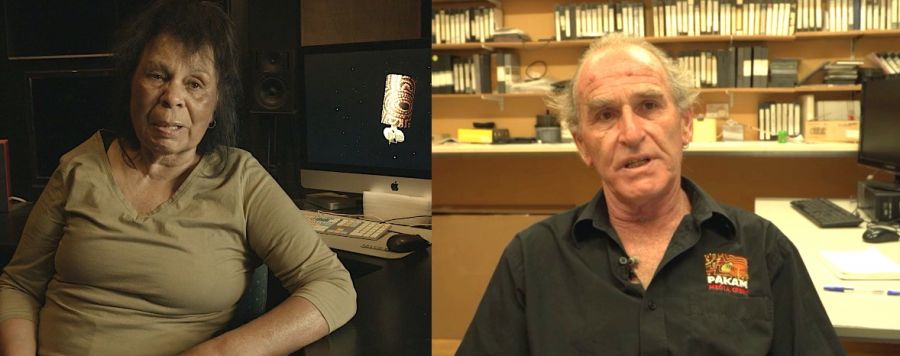

Warwick Thornton & Cilla Atkins

Two of the Aboriginal employees at CAAMA who worked on it – Warwick Thornton and Cilla Atkins – talked about how revealing the experience was. For Warwick:

‘It was interesting you know working at CAAMA, you know you spent a lot of time in the bush. […] and then suddenly going and doing Satellite Dreaming, and then standing right back and seeing the whole forest of what was happening in Australia at that time […] that was just was an incredible eye opener.’

And Cilla: ‘…you never kind of sit down and go back in history and say, well, how did it actually start? You know, how did you actually do this? So, you know, for me, who'd been working in the media for a while, it was it was so interesting to see how they came about developing Aboriginal media back in that day.’

Tanya Denning-Orman & Jennifer Deger

It was also exciting to learn of the programme’s impact on others who weren’t involved in the production. For Tanya Denning-Orman

'Satellite Dreaming was pretty much part of my university degree and education […] a recommended viewing was Satellite Dreaming. […], definitely a part of my foundation in the sense it gave me a bit more of an insight of the world that I was about to enter’.

Jennifer Deger came across the programme at University too:

'I decided to do a PhD in anthropology and became really interested in indigenous media as it was rolling out across the continent. And Satellite Dreaming was one of the first things I came across. And so, I sat down, kind of enthralled because there was a guide really to what was going on…'

The programme also attracted some detailed analysis and criticism, some of it from participants. Dion Weston thought it was ‘a very naive style documentary […] the production values were […] pretty loose, pretty crude. I think it could have been […] a bit more slick’. And Nicolas Lee, the editor, commented:

‘I don't mean to demean it all, but it was almost planned like a corporate video - like every … every interview was targeted. You knew exactly what you're going to ask them […] apart from one point. It was about eighty percent of the way through the film where there was a spontaneous song and dance [which] erupted or just happened before the cameras’.

This was the ‘spine tingling’ Kuruala sequence he commented on above.

Rosie Kumalie Riley & Neil Turner

For two other participants, Rosie Kumalie Riley and Neil Turner, being involved in the programme was complicated by the fact that their own filmmaking practice was so different from how we made Satellite Dreaming. For Rosie:

'…to me, as a language speaker and Language Coordinator […]at that time, it was like something different from what […] we're used to doing in our programmes in Nganampa Anwernekenhe. […]. With Satellite Dreaming, […] it wasn't a reality for me as an indigenous person.'

Neil contrasted his experience of filming the ‘Seven Sisters’ story, which EVTV repeated for Satellite Dreaming:

'I suppose in a purist sense, I preferred the recording that had been done at Kuruala the previous year, that was entirely directed by the participants […] Doing it again with a professional film crew […] I got some amusement out of the set-ups for convoy shots and so on, and Ivo waving the cars past. And these were things that we just simply didn't bother with in the, in the pure form of recording the story and song and dance and landscape for Pitjantjatjara people. So it was sort of interesting that some of those conventions of documentary and so on, were being applied on this second trip.'

In both these cases I think that the norms of mainstream, ‘whitefella’ documentary making (which we were following) were rubbing up against the filmmaking practices more common in remote communities.

For Tanya Denning-Orman it was clear that the programme

‘was created by a non-indigenous person.[…] And I do wonder what ‘Satellite Dreaming’ would have been like if it was created by […] an indigenous person, because the lens and how we're placed in the documentary, it would be different. So we're not ‘otherising’, we're not talking about indigenous people in a certain way. We're talking about the story and the experience and the observations from our perspective’.

Frances Peters-Little & Rhoda Roberts

Frances Peters-Little and Rhoda Roberts, both former Indigenous television professionals based on the East Coast, were conscious of the Central Australian bias in the programme. Rhoda asked:

Was ‘Satellite Dreaming’ too focused on Central Australia? Look, I think there's a couple of elements there. One was the fact that CAAMA had grown out of central Australia. […] that focus that you're not a real Aboriginal unless you come from the Central Areas - which is just a load of bollocks, but they did, I guess, romanticize….

For Frances

there seemed to be a sort of an idealization of that, that the ‘real’ Aboriginal television, the real, you know, purity of Aboriginal Film and Television making only came from Central Australia. And I think that's, you know that's …downright wrong. And I think it's also a little bit racist. I think it's …it's a bit ‘noble savage’ in my mind that, you know you have to only be a ‘real’ Aboriginal person to make ‘real’ Aboriginal films. I thought that was naive, and I think it was disrespectful to us. And we were working… we were ‘real’ too, you know, and it was because we were urban, and we were working for […] a national television broadcaster.

Frances expands on this critique of the ‘noble savage’ in her essay 'Nobles and Savages' on the Television on this site, where she also highlights the work of East Coast figures like Lester Bostock. The story he tells about his life and work in his interviews is one that I'm now sorry was not better represented in Satellite Dreaming.

Another effect of the Central Australian focus of Satellite Dreaming precursor of these divergent approaches to the television medium is evident in the way the CAAMA and the development of Imparja Television is dealt with in the programme. What we presented was a clear-cut conflict between commerce and cultural maintenance, a conflict that was clear from the beginning of the AUSSAT licensing process.

Philip Batty & Freda Glynn

As Philip Batty, Deputy Director of CAAMA at the time, put it to me in 2011:

'We just wanted access, but we were forced by the Government's change in direction to go for a complete licence - which meant running a commercial television service which is not what was the original intention at all. We're a community-based service specifically to develop programming – television, radio etc. - for Aboriginal people, not to run a commercial service.'

The problem was that

'Imparja had to make money from the production of local advertising, and the purchase of national advertising, on the one hand. On the other hand its facilities had to be used to make television programmes for Aboriginal people. Now, advertisers would buy lots of time on Dallas and the commercial news service and commercial programmes, but they'd buy almost no or none, no time at all on the Aboriginal programmes.'

For Philip and Freda Glynn (then Director of CAAMA)

'it just came to a head and we said 'Look what have we done? This was won on the basis on the promise of running Aboriginal services. Not only is the production equipment being used for commercial production, we're getting, we're getting squeezed for time more and more’…'

Dion Weston & Alastair Feehan

Ironically, Imparja was from the start an Aboriginal owned Company, run by an all Aboriginal Board. For Dion Weston, the (non-Aboriginal) General Manager of Imparja Television at the time, the priorities were clear:

'We had a task to do to fulfil the requirements that the shareholders of Imparja wanted, and that was that they wanted a…they wanted a television station that wasn't going to go broke.'

And on that basis the Board backed Dion rather than Philip and Freda, who said later:

'The Board had decided that Philip and I were no longer relevant to what was happening in the organization, so they asked us to finish up. So we did. I walked out the day that I got the information.'

These commercial pressures on Imparja have continued to inhibit Aboriginal programming. Alastair Feehan, the current CEO of Imparja, painted a very similar picture when I interviewed him in 2011:

'I just need to keep reminding the Board every so often, is that ‘Look, if you don't go down this path and you fail as a business, you're another failed Indigenous business’ - and sometimes the board would like to see more and more, say look ‘… we're an Aboriginal television station’. And my answer to that is […], ‘…no, we're a television station and we're owned by Aboriginal people. So, do you want to have a successful business that's owned by Aboriginal people, or do you want to have an Aboriginal television station, which really at the end of the day could go broke very quickly?’'

Despite the difficulties with Imparja, it remains true that that CAAMA's achievements in the indigenous media sector are impressive. As Philip Batty points out, there

is now, an extensive Indigenous media sector across Australia. This sector now contains a large group of talented Aboriginal filmmakers, broadcasters, script writers, directors, producers and other media workers who were entirely absent before CAAMA was established. (Batty 2021)

Over the years CAAMA has proved to be a highly successful training ground for Aboriginal people who want to make careers in the media. Cilla Atkins remarked how:

'a lot of our filmmakers are making, you know, huge feature films. We've gone up to the next level now. You know, we've done the short films, we've done the documentaries, we've done the television dramas. And now we're actually doing feature films with, you know, well recognised actors in it. So, you know, it's … a great place to be. And I can see it just growing even further.'

This is true in the television industry, as well as feature films. Rachel Perkins was another CAAMA graduate, and a successful writer and director with Blackfella Films, who have produced many successful films and TV programmes. These include the documentary series The First Australians, and Redfern Now (the first drama series written, directed and produced by Indigenous Australians).

Nicolas Lee also emphasises CAAMA’s

'remarkable history of training of, you know, some of the leading filmmakers in this country. I'm not saying Aboriginal leading filmmakers. I‘m saying leading filmmakers, the top award winners…'

Philip Batty remembered (at the time of CAAMA's successful AUSSAT bid) how Eric Michaels:

'was very critical at the time of Imparja……On one level he's turned out to be right. […] he was saying at the time that the focus in terms of funding should be on remote communities and small community groups and not on a big organization like Imparja. It will lead to a disaster, and he's absolutely right. And that did happen. So, we should have listened to ‘saint Eric’ on that score…'

I’ve mentioned above the many critiques of Michaels work, but as Jennifer Deger said he still ‘remains a kind of touchstone figure…’ in the sector, and a such was frequently mentioned in the interviews. For instance, Tanya Denning-Orman remembered how at University ‘there was the document called The Aboriginal Invention of Television’ , and Francis Jupurrurla Kelly talked about how

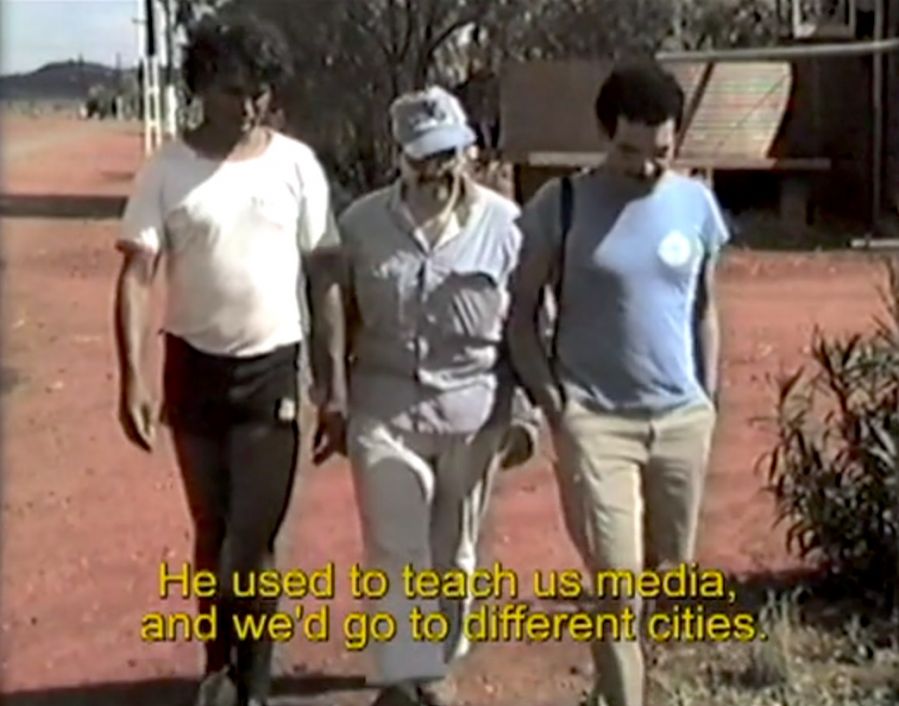

'An American man came to Yuendumu named Eric Michaels. He used to teach us media….'

For me, one of the most interesting of the critiques of Michaels is Melinda Hinkson’s ‘New Media Projects at Yuendumu’, reproduced and updated on this site. She questions

Michaels’ unproblematised deployment of the concepts of ‘cultural maintenance’ and ‘traditional modes of cultural production’. In his terms, a ‘cultural future’ will only be realised if the Warlpiri can ‘embed [video] production in traditional forms’ (Michaels & Kelly 1984: 34). There is a false dichotomy implicit in this statement—between traditional and modern, culture and lifestyle and, indeed, local and global—that assumes cultural reproduction to be a static process. In Michaels’ accounts ‘culture’ is reified as a set of aesthetic practices or ‘systems’ to be preserved…

Philip Batty confirmed this view of Michaels:

'…he had a real essentialist idea of Aboriginal culture. You know he - even though he denied absolutely you know - he saw Aboriginal culture as this sort of carved in stone, traditional thing […] the focus should be on Aboriginal men, you know people catching kangaroos and things like that…'

L-R: Francis Kelly, unknown, Eric Michaels (Still from Jupurrurla, Man of Media)

Melinda Hinkson also makes the point that

The Warlpiri Media Association portrayed in Michaels’ accounts was represented as an almost entirely Warlpiri affair […] Michaels revealed little of the role he himself played in shaping the early period of Yuendumu’s engagement with new media.

Yet his role was clearly one of very active ‘inter-cultural engagement’ as Francis Jupurrurla Kelly’s account of how ‘he used to teach us media…’ reveals:

'…we’d go to different cities, like Brisbane in Queensland and Canberra. We went to the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, where we looked at the Aboriginal artefacts. He was a good worker teaching us all of that.'

David Batty’s memories of Michaels’ arrival in the area confirm his active, interventionist role:

'…he kind of checked in to Yuendumu and he kind of thought “Wow this … is a bit bigger, this is something, these people here are slightly more worldly than other people around Central Australia. I could do something here”. […] So,…he … went to Canberra where he was based with the Institute of Aboriginal Studies, and he came back with this truck. And the truck was all decked out with all these monitors, and he had the latest little TV cameras and spent a whole chunk of his of his grant money or his budget, or whatever he had, to equip this Toyota with all this gear and stuff.'

Daniel Featherstone and David Batty

Michaels may have underplayed the ‘inter-cultural’ aspects of his work, but his influence on work in remote communities has certainly persisted. Daniel Featherstone acknowledges the importance, in his own work, of Michaels rejection of:

'this sort of pan-Aboriginalist model, of expecting all Aboriginal people to take on a sort of a similar identity, as compared with a cultural maintenance model which is very much about maintaining the intricacy, what is different and unique about a particular place and a particular cultural identity. And you know, my experience at working at Ngaanyatjarra Media has been very much along a similar line to what was established at Warlpiri Media and Ernabella Video and TV with that sort of cultural maintenance model.'

Key to Michaels vision of video’s role in cultural maintenance was his belief that, in Warlpiri hands, the camera reveals a ‘radically Yapa [Warlpiri] sense of mise-en-scène’ (Michaels 1994: 115). He was responding to the ‘recurrent camera movement […] during the otherwise even, long pans across the landscape’ that Francis Jupurrurla shot for ‘The Conistion Story’. Michaels wondered whether these movements were due to ‘a simple lack of mechanical skills’, but said that Jupurrurla denied this, and told him that the pans followed ‘movements of unseen characters – both of the Dreamtime and historical – which converge on this landscape’. (115)

However David Batty was dismissive of Michaels' ideas about a specifically Warlpiri style of filmmaking:

'I think it's a whitefella notion to be thinking that they are using this to do this thing in a particular way that that's really only, that's got to do with their perception of …reality or they're … I just think that's a bit of an academic wank myself…I don't think that's true, all that stuff, Eric made all that up, I think just so he could go to conferences and talk about that sort of stuff.'

Nevertheless for many people the idea of a specifically Aboriginal film aesthetic still has a powerful resonance. Freda Glynn echoed Michaels when she described affectionately how in CAAMA’s Nganampa Anwernekenhe series:

'People would sit for hours and do dreaming stories …just in the shade of a tree. And that's where the whole thing, the whole series would be listening to this old man telling a story. What did they used to call it? They called it the Nganampa pan – a slow pan across the country while they're telling the stories.'

And Warwick Thornton, now one of Australia’s best known indigenous filmmakers, believes:

'…being a blackfella I think we have a very unique perspective on storytelling. You know, we might use the same format and the same kind of composition and the same editing styles, but […] it boils down to something deeper than that, which I think comes from maintenance of who we are and where we come from[…] whether you…grew up in a very remote community, or you grew up in a city, you've got very different sort of connections to cinema or television in a sense - and that does dictate to you how you make a film, […] that sort of connection to country and community and how you show it…'

The potential cultural connection between city and remote Aboriginal communities that Warwick points to above, was severely tested by the conflicts around the establishment of NITV - the 'shitstorm' mentioned above. Divisions emerged between the urban and remote sectors in particular between those setting up NITV, and those associated with ICTV. The root of the conflict lay in their divergent visions of an indigenous television service, as well as the Government enforced competition for scarce resources. Both sides would have agreed with Tanya Denning-Orman from NITV that ‘we need a place, we deserve a place in the Australian media landscape because our communities need to see themselves…’ Tanya also argued that

'you've got a divided sector because there's only so much that is going around [..] the narrative of a divided sector […]played into what the federal government needed in order to not give indigenous media its …rightful place in Australian media landscape.'

Kim Dalton & Owen Cole

And Kim Dalton, who was Director of ABC TV at the time, felt too that scarcity of resources was the main problem, because in his view the sector needed

'substantial dedicated funding as in as in 10, 15, 20, 25 million dollars put into an Indigenous screen fund […] to be getting stuff up into prime time, into the mainstream. […] that's what it costs to run a TV station. It's an expensive medium. […]. I don't know what the NITV budget is, but it's tiny. It's absolutely tiny. And I, I just feel like what happens is it ends up being sidelined…'

Owen Cole, who was on the CAAMA Board but also part of the group that set up NITV, said he

'always tried to be the mediator, tried to get people to work together but it just didn't… work out and it became either/or…I think it came down to in the end that there was this notion that you know, NITV - even with its small budget - somehow was the quality end of production. And ICTV wasn't up to that standard. […] You know, it was a bit ‘elitist’ on both sides: one who thought they were ‘quality’ and one who thought there was… the ‘traditional’ versus ‘contemporary’ and so forth, and never the twain shall meet unfortunately.'

Daniel Featherstone (the Manager of remote media organisation Ngaanyatjarra Media at the time, so in the 'traditional' camp) thought that the problems originated from the fact that

'the government insisted that there be a single service and that everyone worked together. […] it left the programming model up to the board of NITV, […] which was very much a black SBS – a mainstream type model.'

And for Neil Turner (also involved with remote media and ICTV) this meant that

'we had to compete with other, more professional and commercially based video producers for commissioning dollars, which put us through a lot of hoops and paperwork and so on. We had to provide content to television 1/2 hours or quarter hours instead of our loose formatting of any duration goes.'

On the other side of the debate, Cilla Atkins, who was also part of the original group that planned NITV, pointed out that

'ICTV wanted to run, you know, two, three hour programmes. And we're like, well, you can't do that on a television station because you've got set time frames. […] NITV would be more of a, more structured like a normal national television.'

In the end these arguments have begun to be resolved by both ICTV and NITV being separately resourced. In Neil Turner’s view this happened,

'with the transfer of the NITV service to SBS, and I think perhaps, Government realising that there might be backlash on the cutting out of spectrum for community television, generously offered a subsidy for a full satellite channel […] where ICTV have now taken over their own playout and are funded fully for the service, including the satellite uplink costs. So, at last we had the full time channel back and we haven't looked back since.'

Jennifer Deger, while acknowledging that NITV ‘is a success…it's watched by a lot of people…’, now also sees the ICTV Channel as the

‘portal for much more community-based production [which] is a really important aspect not to leave out of the picture […]there's this whole other level of activity that's much, much less organized and, as a result, much more vital’.

Perhaps the most visible evidence of the subsequent healing of divisions in the sector came with the setting up of First Nations Media Australia, which became the ‘peak body’ for the whole of the indigenous media sector in 2016-2017. Tanya Denning-Orman has talked about how ‘one of the things I'm proud of is to be on First Nations Media Australia as well…’, and is pleased that NITV ‘has partnerships with remote media all over the country now […] we go direct because we're like, your indigenous media in different places want to work with us differently.’

Daniel Featherstone’s essay on this site also explains in detail how effective national organisation of the remote sector within this new ‘peak body’ has been.

Clearly the most dramatic change in media worldwide since 1991 (of course not referenced at all in Satellite Dreaming) has been this development of digital and web-based technologies (including social media and mobile phones).

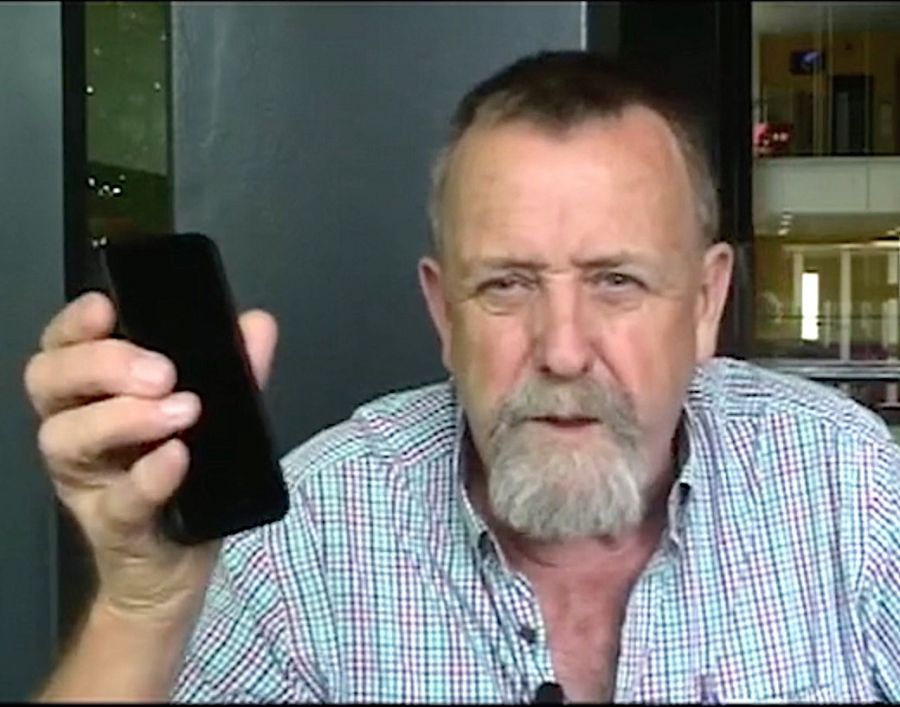

Clive Scollay, still from interview

In his 2017 interview Clive Scollay remembered how '…when I first started, we thought video was completely unique and a great production tool.’ Then he held up his mobile phone: ‘This is everything […] This is a production tool. This is everything in one. And I think understanding how to use that and social media nowadays is probably where things are headed.'

Indigenous media makers in Australia have made use of mobiles and the internet no less than those in any other media industry worldwide, but for their own particular reasons:

The uptake of media technologies by indigenous producers – from the old analog format of U-Matic widely used in the 1980s, to contemporary digital social media platforms such as YouTube and mobile phones – has often been motivated, at least initially, by a desire to “talk back” to structures of power that have erased or distorted indigenous interests and realities, and denied them access to dominant media outlets. (Ginsburg 2016: 582)

There is an enormous amount of writing on this issue, too much to describe in any detail here [3]. I have tried as much as possible to highlight the issue in Satellite Dreaming Revisited, both in the Sources pages and the Interviews, where in many of them, these digital transformations became a major theme.

For instance, Frances Peters-Little, who, when I spoke to her in 2018, was not working professionally in film or television, outlined how:

'…with the technology, with social media, I still, you know, do things. There was a time when, you know, I had a hip operation, and I wasn't I wasn't very mobile. And so I did a series of short films called From My Car. And I'd just use my phone. And you know, and I've been filming little short bits and pieces, a series from my car. And I thought, there's ways of being able to go on YouTube, or if you're disabled or if you're a certain age or if you have no technical experience or background, you have access. And it's open now, we can all make these films - they don't have to be for great big wide audiences, you don't have to walk down a red carpet.'

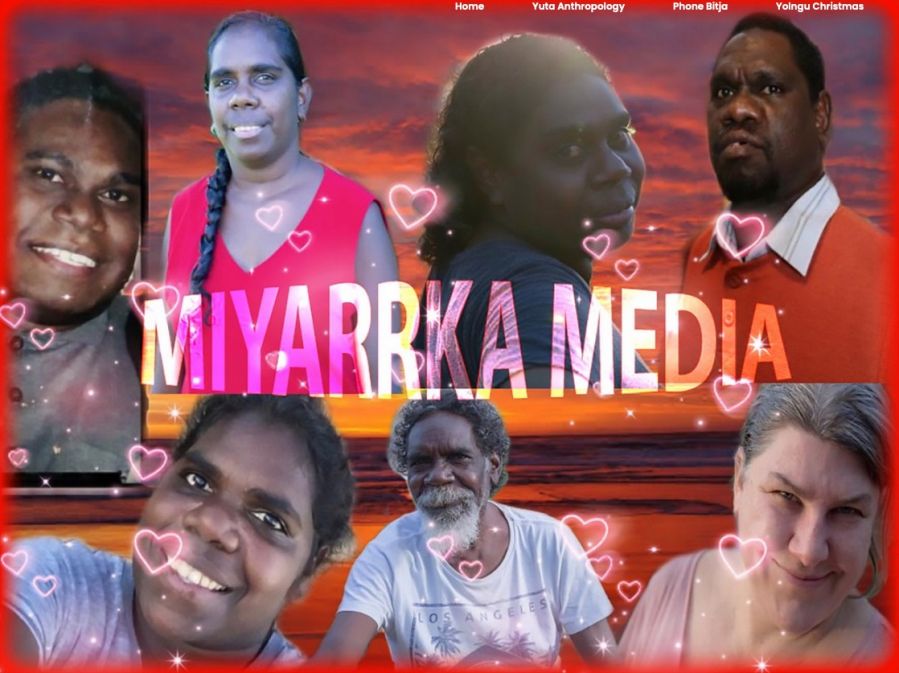

A still from Gapuwiyak Calling, an exhibition curated by Miyarrka Media

Jennifer Deger and Miyarrka Media, also make extensive use of mobile phones because they

'…gave people an opportunity to, to remediate their own culture […] It seems to me that, that mobile phones […] and the networks of connection that they enable, which are obviously of a very different order to any kind of broadcast - whether it's […] a national broadcaster or remote community broadcasting - have really challenged the model that was set up all those years ago.'

Ivo Burum has also challenged this model in his Mobile Journalism project:

'…for you know under a thousand dollars you can have a broadcast quality production kit, so you can have a number of them in the communities - all that's left to do is to teach people how to use it.'

In 2012 Ivo's project NT Mojo enabled young, indigenous mobile journalists from six remote communities in the Northern territory, to use mobile phones at a local level to create and publish their own stories.

Digital technologies are also in widespread use as cultural maintenance and archiving tools. For instance, First Nations Media Australia have set up their own Archiving Project, and since 1994 Aṟa Irititja has been archiving still and moving images from the Anangu lands. John Dallwitz was engaged by the Pitjantjatjara Council to develop this archive, which started with ‘some senior men coming down to Adelaide to have a look at the South Australian Museum and the State Library, which they knew had collections of photographs from the 1930s and 1940s’. They told him:

'…'we want them all back again’. So, of course that posed certain logistical problems because ‘back’ meant out to the desert where they were there were… no facilities… there was no air conditioning, there's dust,…that's where the computer came in, and computer technology was something where we could, we could reproduce things digitally, and we could present them out there…'

There are many other indigenous uses of the web. For instance AIFTV Research is a website, very similar to Satellite Dreaming Revisited, which also aims to be a 'platform for sharing knowledge, ideas and resources about Australian Indigenous film and television'. And IndigenousX is a '100% Indigenous owned media, consultancy and training organisation' with an online Newsfeed.

Clearly though, we should beware of celebrating all digital technologies and social media uncritically, particularly in remoter communities. To cite just two notes of caution, Melinda Hinkson makes the point that despite the

widespread take-up of mobile phones and related social media by those who live in the desert […], communication afforded by mobile phones differ[s] markedly from the dense bodily engaged sociality that is a requirement of human intimacy and vital to desert modes of interaction. (2021: 19)

And the book Internet on the Outstation (Rennie et al 2016) makes it clear that there is still a substantial and complex and damaging Digital Divide in remote Aboriginal communities. Nevertheless, from the evidence I’ve gathered in the process of making Satellite Dreaming Revisited, I'm with Faye Ginsburg:

While indigenous access to digital platforms is certainly uneven, we have ample evidence for the creative uptake of new technologies in indigenous communities on their own terms, furthering the development of political networks and the capacity to extend their traditional cultural worlds into new domains. (2016: 592)

I wrote ‘Will it Harm the Sheep?’ (Dowmunt 2015) in the few years immediately following my first research trip to Australia in 2011. That essay now seems to me to be an attempt to come to terms with how and why my hopes and expectations of untroubled progress in the field were not always met in the different realities that I was confronting during my research. I have a more rounded and optimistic view now than when I wrote it. I have been made aware of many exciting and substantial developments over the last few years of my research, both in the remoter communities and in the national media - and many of these are recorded on this site.

Nevertheless, some other interviewees’ assessments of the future of 'cultural maintenance' in remote communities are pessimistic. David Batty points out how

'…. everyone just watches TV like we all do now…I think there’s…a lot more consumerism. People want a lot more things of the, that the white men […]I think consumerism […] just had a huge impact on Aboriginal people. I think, I think it's just too much. […] I don't know whether things ever will improve.'

Black Lives Matter demonstration, Sydney 2020 (© ABC)

Philip Batty is now profoundly sceptical that ‘changing media will change much in the broader situation of people’, pointing out how

'the general position of Aboriginal people in Central Australia - for the worst off of that community, most underprivileged section of the community, which is the majority in Central Australia - are no better off than they were when we started this 30 years ago. They're worse off. I mean health, in the level of domestic violence, in levels of incarceration, poor educational levels, it's just as bad.'

He expands on these points in greater detail in his essay on this site. There are clearly hard, inescapable facts in relation to continuing indigenous impoverishment and exclusion, but these don't necessarily negate the global importance for all of us of the lessons of Australian indigenous media, or the ways in which our 'liberation is bound up with' theirs. Faye Ginsburg has written that indigenous media

…show how the medium can be reimagined to promote and develop the cultural resurgence of minoritized communities, providing a provocative case study around which the global impact of television can be re-examined and understood. (Ginsburg 2011: 245)

She also remarks how

Scholars and researchers have been attracted to indigenous television since the mid-1980s, seeking in it the empirical evidence for a kind of embedded cultural critique, and aesthetic and political alternative to mass media that is beholden to governmental or late-capitalist interests. (Ginsburg 2011: 247)

One of those 'scholars and researchers' was certainly Eric Michaels, who saw Aboriginal experiments with media as 'a test of and an analogy to questions posed within the modern Western tradition. Ultimately, I wanted to understand our, not their, media revolution.' (Michaels 1994: 22)

In that spirit, I'm interested in finishing this essay with a brief summary of some of the lessons from my research for this site, and particularly from the interviews. I do this from the perspective of someone who is as much of a UK media activist as a 'scholar and researcher', attempting to draw out how Indigenous media in Australia resonate resonate with ours, what the lessons might be for our 'media revolution'.

To return to the limitations of 'binarism' that I wrote above, I am now uncomfortable with the 'clear binary and oppositional relationship' between the national mainstream and its local, community-based alternatives, that I have previously championed. The extraordinary successes of indigenous people in Australian feature filmmaking and national television indicate that both the national and the local (or 'community') contribute to the Aboriginal 'media revolution'. (For this reason I also now question the focus on remote work at the expense of the more ‘mainstream’ or national work that Satellite Dreaming - the original programme - tended to exhibit). Any worthwhile 'media revolution' needs to involve both the 'marginal' and the 'mainstream'. Each has its own value, and shouldn't replace or surrender to the other.

The history of the fractious relationship between CAAMA & Imparja demonstrates above all else the necessity of substantial public funding for indigenous media, to curb the power of the global media marketplace. Imparja's failure as an 'Aboriginal TV station' committed to 'cultural maintenance' is attributable from the start to its commercial structure, and its consequent pressure on it to succeed as an 'Aboriginal business'.

The lack of substantial public funding available in the early stages of the founding of NITV was certainly also one of the factors that led to the NITV/ICTV split and to the divisions between ‘remote’ and 'settled' media-making communities that it exposed. The experiences of both Imparja and NITV underline the case for substantial public funding of all 'public service' and alternative media.

These divisions are of course as much cultural and geographical as they are economic. So, the NITV/ICTV debate points to the importance of the acknowledgement of difference within communities (ethnic, place-based or communities of interest), and of inclusivity over homogeneity in all forms of 'alternative media'. As Frances Peters-Little puts it, in the Australian context, 'we aren't going to be homogenized, we are going to continue to make Aboriginal films in our way, for whatever reason and wherever we are.' I'm hoping that this site promotes an indigenous media culture that embraces the value of both the remote and coastal communities, and more broadly makes the case for inclusive diversity in all our 'media revolutions'.

L-R (top row): James Ganambarr, Meredith Balanydjaark, Enid Gurunulmiwuy, Warren BalPatji; L-R (bottom row): Kayleen Djingadjingawuy, Paul Gurrumuruwuy, Jennifer Deger. (© Miyaarka Media)

There is a theme in many of the interviews, often implicit, occasionally explicit, about the role of 'whitefellas' in helping to nurture indigenous media, particularly in remote communities. The number of significant collaborations and partnerships between indigenous and non-indigenous people is remarkable, for instance: John Macumba and Freda Glynn with Philip Batty, Francis Jupurrurla Kelly with Eric Michaels and David Batty, Simon and Pantjiti Tjiyangu with Neil Turner, Noeli Roberts and Belle Davidson with Daniel Featherstone, and Bangana Wunungmurra and Miyaarka Media with Jennifer Deger, who describes an 'overt, explicit invitation to be involved, to participate in forms of co-creativity…' from her Yolgu colleagues in Miyaarka Media. Particularly in the light of Melinda Hinkson's crititique of the way in which 'Michaels revealed little of the role he himself played in shaping the early period of Yuendumu’s engagement with new media', I think it's important to acknowledge, analyse and celebrate these active ‘inter-cultural engagements’, in Australia and more generally.

Finally I would echo Philip Batty in advocating a modesty about the capacity of media - by themselves - to effect social change. At the very least media work needs to be embedded in wider social and political movements to realise its full potential.

And along with Faye Ginsburg again, I would like to

conclude on a note of cautious optimism. The evidence of the growth and creativity of indigenous media over the last two decades, whatever problems may have accompanied it, is nothing short of remarkable, whether working out of grounded communities or broader regional or national bases. While indigenous media activism alone certainly cannot unseat the power asymmetries that underwrite the profound inequalities that continue to shape the activists’ worlds, the issues and images that their media interventions raise about their cultural futures are on a continuum with the broader issues of self-determination, cultural rights, and political sovereignty and may help bring some attention to these profoundly interconnected concerns. (Ginsburg 2011: 253)

On October 11th 2011, a few nights before my trip to Australia to begin the research for this website, I had the following dream:

The Interpretation of Dreams – painting by Rod Moss (©), 2009

I’m on a rocky ledge above a river. The rocks are black and slippery and I’m frightened of slipping over. I’m here to do an initiation ceremony with three middle-aged Aboriginal blokes, and I’m apprehensive.

I have a white ceramic Victorian-style jug with me that I took from a house or hotel up the riverbank. I planned to use it in my initiation, but I see now that it’s not suitable. I put it down near the bank on the ledge, worrying about how I’m going to get it back to the hotel. One of the Aboriginal guys is already in the water, fully clothed – he’s swimming strangely on his side, one handed, his face cradled in his other arm to keep his nose out of the water.

Then Zosia [my daughter] is with me. She describes an ‘initiation ceremony’ she’s going to do which sounds more like a teenage sleepover to me – the plan is to watch DVDs all night with a group of friends. I don’t approve, this is not a ‘proper’ ceremony.

I tug at a long (20-30ft) root that snakes its way across the rock I’m standing on, but then decide not to pull it up: that would kill it, be a desecration. Then I look down the river and all three Aboriginal guys have swum a long distance – maybe too far for me to catch up – and I realise I’ve missed my chance to be with them. They are swimming towards, and in, this sunlit stretch of the river: it’s idyllic, there’s someone standing up in a raft, it’s a picture of an unspoilt paradise.

Footnotes

I talk more about this history here

Wendy Bell (2008) describes this process in detail.

See, for instance: Ormond-Parker, Corn, Obata, & O’Sullivan 2013 / Carlson. & Frazer 2021 / Carlson & Berglund 2021 / Rennie, Hogan, Gregory, Crouch, Wright & Thomas 2016.

I talk more about this history here

Wendy Bell (2008) describes this process in detail.

See, for instance: Ormond-Parker, Corn, Obata, & O’Sullivan 2013 / Carlson. & Frazer 2021 / Carlson & Berglund 2021 / Rennie, Hogan, Gregory, Crouch, Wright & Thomas 2016.

Batty, P. & O’Regan, T. (1993), ‘An Aboriginal television culture: Issues, strategies, politics’ in O'Regan, T., Australian Television Culture, St Leonards, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin

Batty, P. (2021) 'What’s Wrong with this Picture?: Personal Reflections on Developments in Indigenous Media in Australia' - On this site.

Bell, W. (2008) A Remote Possibility - The Battle for Imparja Television, Alice Springs, N.T.: IAD Press

Burch S, Gye L, Horswood K-L, Marcus D & Vodeb O (2020) ‘Coming to the Fire: Collaboration across Cultures in Media Activism’ in Rob C & Charbonneau S (eds) Insurgent Media from the Front, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp109-129

Carlson, B. & Frazer, R. (2020) “They Got Filters”: Indigenous Social Media, the Settler Gaze, and a Politics of Hope” Social Media + Society, Volume: 6 issue: 2, Article first published online: June 10, 2020; Issue published: April 1, 2020

Carlson, B. & Berglund, J. (Eds.). (2021). Indigenous People Rise Up: The Global Ascendancy of Social Media Activism, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press

Carlson, B. & Frazer, R. (2021, forthcoming). Indigenous Digital Life: The Practice and Politics of Being Indigenous on Social Media, London: Palgrave McMillan

Coyer, K., Dowmunt, T., & Fountain, A. (2007) The Alternative Media Handbook, London: Routledge

Dowmunt, T. (1991) 'Satellite Dreaming: Making a TV documentary about indigenous people's television in Australia', Artlink, 11 (1 & 2), pp. 39-40 & 45.

Dowmunt, T. (1997) ‘Heat from a Small Fire’, Soundings magazine, issue 5, Spring 1997, pp. 203-208.

Dowmunt, T. (2015) ‘Will it harm the sheep? Developments and disputes in central Australian indigenous media’ in Atton, C. The Routledge Companion to Alternative and Community Media London: Routledge, pp. 469-79.

Ginsburg, F. (2011). ‘Native Intelligence: a Short History of Debates on Indigenous Media and Ethnographic Film’, in J. Ruby, & M. Banks (Eds.), Made to be Seen: A History of Visual Anthropology (pp. 234-255). University of Chicago Press.

Ginsburg, F. (2016) ‘Indigenous Media from U-matic to Youtube: media sovereignty in the digital age’ sociol. antropol. | rio de janeiro, v.06.03: 581 – 599, december, 2016 (https://www.scielo.br/j/sant/a/ynp7fXFyfRshZRZqQQchYbB/?lang=en – accessed 22/10/2021)

Michaels, E (1994) Bad Aboriginal Art Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Ormond-Parker, L., Corn, A., Obata, K., & O’Sullivan, S,. (eds) (2013) Information technology and indigenous communities. Canberra: AIATSIS Research Publications

Rennie, E., Hogan, E., Gregory, R., Crouch, A., Wright, A. & Thomas, J. (2016) Internet on the Outstation: The Digital Divide and Remote Aboriginal Communities, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures

Rijavec, F (2010) ‘Careless, crude and unnecessary’, ABC News (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-07-20/careless-crude-and-unnecessary/2508286 - accessed 21/10/2021)

Rodriguez, C. (2001) Fissures in the Mediascape: An International Study of Citizens’ Media, Creskill NJ: Hampton Press.

Stoneman, R. (2020) When Channel 4 Was Radical, Tribune, 06/202 https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/06/when-channel-4-was-radical (accessed 27/06/2020)

Tynan, E. (2016) Atomic Thunder: British Nuclear Testing in Australia, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books

Wilson, A., Carlson, B., & Sciascia, A. (2017). Indigenous Activism on Social Media, Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 21.