John Dallwitz

“The software had to do what they wanted, not the other way around…”

… welcome to our Ara Irititja. It's a Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra project, [a] joint project between these central desert language groups, started in 1994, with the intention to be able to give access out to the desert, out in this country, to historical photographs held in institutions and in private collections all over Australia - to be able to take that back to the people so that they could develop their own sense of history …and teach the kids in the school about the old days, see their families, create their own family histories, and have some control over …their own history rather than have it put away in cupboards and in institutions in the capital cities of Australia.

This little symbol was, was created for us by a young Pitjantjatjara woman. And it represents, the three…three circles represent the past, the present and the future. And the past and the present and the future have two pathways – … it's not one direction, it's two directional. So, things from the past have a relationship with the future and things in the future relate to the past, and the present and vice versa. The little shapes around the outside are people sitting around because these things are also campfires. These are also camps, places - and the places it represents, also the three states, the Western Australia, South Australia and Northern Territory. It also represents the three languages: Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra… And it also represents the land, the mind, the people and the spirit - so that … the three circles had many layers of meaning.

Well in fact what we're looking at now is photo number one which was put into this into this computer, into a computer 17 years ago, and it was the result of a trip of some senior men coming down to Adelaide to have a look at the South Australian Museum and the State Library, which they knew had collections of photographs from the 1930s and 1940s.

And those men came down because they also believed that amongst those photographs were some secret, sensitive materials, and they wanted to make sure that the people in, in Adelaide were looking after these photographs properly. And they also wanted to have a look at them themselves. They knew they existed…

And those two old men who came down to the State Library, took one look at this and they said ‘Amazing, amazing. That's not, we don't do that anymore. Those drawings are not used anymore. This this whole sequence… really has been lost. That …tradition has been lost. And we know about it as old people and we would like to get it going again. So, we need all this stuff. We want it back. We don't want it down here …in the library in Adelaide. We want it out in the bush - we can see it ourselves, and where we can show it to the kids, and where they can all participate again…in these ceremonies’. And that's exactly what happened…

These two these two elders just said to myself and the anthropologist who was with me, that ‘Whatever you do just go and… I don't care how you do it, don't care where you get the money, just go and get it. Get them all, and we want them all back again’. So, of course that posed certain logistical problems because ‘back’ meant out to the desert where they were there were… no facilities… there was no air conditioning, there's dust, there was mice, there were rats and blowflies and things all over the place. Tomato sauce and chops and …raw steak: not the sort of things that go well with fragile historical photographs. So…that's where we came to the feeling that we what we really needed to do, was to do something which was able to be reproduced as many times as we liked. And that's where the computer came in, and computer technology was something where we could, we could reproduce things digitally, and we could present them out there - and it didn't matter if something got damaged, we could replace it because we'd have another copy, or more copies in Adelaide, and we didn't have to take these photographs out to do that job.

At the same time, they said ‘Well you better start looking for more things, we want more’. And we made contact …with some of the old missionaries, and we were able to get movie films that had been made during the time of the mission days. This is an old black and white, black and white movie of a 9.5mm, which is a strange format. It was not a very stable format, and it was one where the sprockets ran down between each frame, and if anything went out of kilter the sprockets would, the cogs would cut a hole down the centre of the film. So instead of the sprockets being on the side they were at the centre. So not a lot not a lot of that type of movie survived. But we didn't know any of this when we started. We didn't know this existed. It just came to us that we were able to say that this…this became available and people were saying ‘You must go out and find those movies, we want to know about the people who were looking after the sheep, and the people who were looking…you know in their first days where they first saw a camera.’ These ones, obviously they didn't know it was a movie camera. So, they were still standing for their portraits to be taken… So we've got examples of the very first time people saw a camera, the first time they saw a movie camera. First time they saw an airplane. First time they saw a motorcar, and we've got that recorded in in this collection.

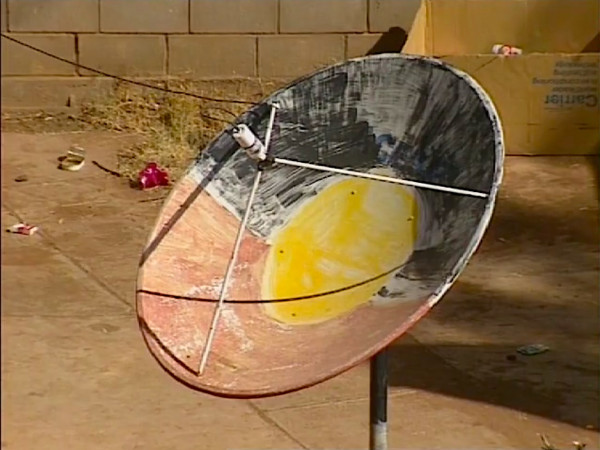

We have a large number of… movies which were created during the time, of the time when …videos were just starting out in in the communities, and there was a period when EVTV started, and along with the Warlpiri media and they… made their own their own movies and we've got these in here. So while… we've picked up … the old VHS, and a special series of bush, bush food - that is here is a movie to play, and we can, people can look back at that and say Isn't that fantastic what we used to do….Well, a lot of long thought a bit long over the intro there. But anyway, here's the movie of … one of the bush tucker, which was a very famous movie which was….produced for the selling to TV, in fact, talking about bush tucker. But now that little movie while it sits here … in its old VHS form, what we can have down here is that … and she's actually making a comment on what she's observing. So she's saying ‘This is lovely. That's Topsy talking, Topsy’s voice, oh dear, it looks like they've not done it right. They've seen it done many times and it actually haven't done it themselves before’. So, she's making a correction. She's making a criticism of this little piece of film that was made in the 1980s. 2011 another one can be made, and today that could be done. And that woman could be, actually her face could be here while she's describing what's going on, what's right, what's wrong with what's happening over here. So, what we're talking about is really is …for it to be a living a living document, not one which is fixed.

The whole thing is designed so that we give them the framework and then out in the communities they are able to add value. They're able to add information, their own personal information. They're able to document people inside the photographs, and in fact even within movies: for example, here is a 16mm movie, and I've got up here a list of things which are in the movie and …I can pick out some of these things. I can find a spear - I've now located that and I can now play that bit of movie. So, they're able to do this themselves. They're able to pick out things inside a photograph or a movie which is of particular interest to them, and that can then be highlighted. And one can move to that place and one can then observe that that little sequence. With photos it's particularly important, because there's a great desire to create, to be able to put the record straight.

When I first went to that library and I found photos of a person, of groups of people, I would find that …the only people who had names on them were the white people. All the Aboriginal people, all the Pitjantjatjara people, there were no names. And these old guys said ‘Well we've got to get that straight, they've got to get names. They [are]… people, they have names’. So the way we did that was, we …created a part of the program … to be able to highlight people according to name, or we can move our mouse across…the screen and that names the people in every photograph.

So now that it's out there in the community the families can look back at these and they can say who these are, they can apply that name themselves, and they can also do more than that. So for Josephine for example, Josephine Mick, I've got a few photographs here of her. You can see … she's here as a little … girl at school. She's grown up to be a healer, a dancer, a singer and a great, and a health worker, a very important health worker. So, we now have a profile about Josephine. We have her date of birth. We have all of the names. Pitjantjatjara people have many different names. Josephine Mick, Watjari, Josephine Scales, Nellie. Over the period of their lives the mission gave them a name and then they got a traditional name. And then they married and, and then if somebody passes away that name needs to be changed because it can't be used again for a while. So, therefore people change their names all the time. So we had to have a facility …that this one person would have that number of names.

One of the other features that we were we thought was important was …to be able to add information in a way which doesn't require the keyboard. So where a person is feeling unfamiliar with using the computer keyboard, we now have a method where they can actually create a movie - and here's a recording for example where … the little camera in the top of the computer has created …this recording of a young woman talking…

So that's Josephine’s daughter giving us a little bit of a biography of her mother. Now that's done directly into the computer…

Now the software, ever since we've started, has had to cater for the wishes of the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra people, and our… right from the very beginning, in 1994, …we had to accept that the software had to do what they wanted, not the other way around. So, when they said we need to have something which protects the privacy of our material, and we need to control it ourselves we need to have some facilities for sorrow, we need to have protection for sensitive material that might not be suitable for children, or might not be suitable for women, or might not be suitable for men. And all of these things we had to do with the software, otherwise we didn't have a project. So, we couldn't turn around and say ‘the software won't do this, or the computers won't do that, therefore, you'll have to change your ways’. That was just…not an option.

So, over the years we've refined that. The new system which we now have running now is and has a warning about sorrow …just in case there's some people are watching who might see something which they're not happy with, then they have to be given a warning…

In the programme that you're looking at today…it does not have any special men's or women's material in it. It is the family, open side of the of the computer. We don't actually combine men's and women's material with open material in the same computer. We don't have …men's material in the same computer as women's material. They can't occupy the same space - just the same as they can't occupy the space in rooms or physical[ly], or in the landscape. They can sometimes, in the landscape, they can take it in turns. But, because a common site may have … streams of…mythological activity, some which may involve men, some which may involve children, which may involve women. And sometimes when they all come together. Now that's not so easy to … justify in a computer which is a much smaller space. People see a computer as having everything concentrated inside it, and consequently if there's something that is sensitive in here, you can't have the crossover inside the one computer. We started off thinking we would …do that, because as white people we thought there's all these security systems and everything. [It] wasn't anything to do with security. It was to do with the fact that the space is shared, and the box is shared. And that was not acceptable. So, this computer doesn't have men's and women's material in it.

Now you'll notice that as we look at things occasionally a comment, a, a little warning will come up that there's got to be, that there might be a person who's passed away. And that is a sorrow warning. I am, as an, as an administrator with you here, I will say ‘Yes. That's okay. We can look at that’. But if that was going out into public it would have to be blank like that. So … at the level of the communities there are a lot of warnings which occur, and people can make the choice.

Simon passed away recently. And I have now…now that I've accepted Simon I'll have a look and see. I may very well have… I've accepted Simon for this session as being viewable because he would want to be viewable. He would want to be on this, is absolutely no doubt about it. …

…there would be no there'd be no question that Simon would, would say don’t leave me out of this program. But then there might be other members of the family who would feel ‘No, no, no …That makes us too sad’. So, I can't really put Simon on here because I don't know what the reaction would be. We have to play it cautiously and that feeling, because we've been very conservative and very cautious about it, we've kept our respect amongst the community for the project and we've never had any issues. We would prefer to avoid the issue – so, although I know what Simon would say about it, would have said about it, I can't be sure. And Pantjiti too: she would have said ‘By all means, show Simon’, but I'm not sure that other members of his family would feel happy about it because it wasn't that long ago that he passed away.