Neil Turner

“A priceless cultural heritage for all of Australia”

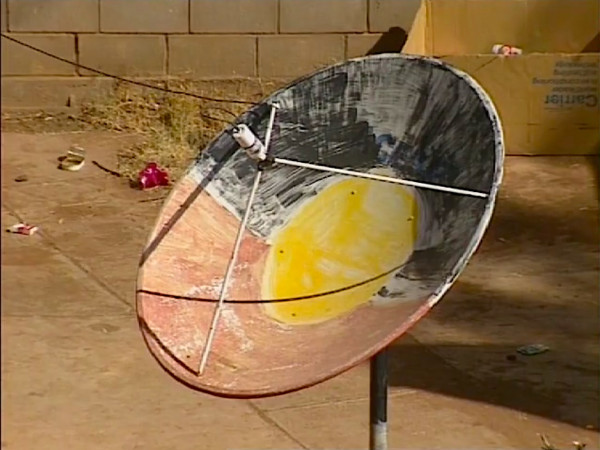

Yes, I remember the shoot for Satellite Dreaming well: 1991, we had been the previous year recording a segment of Seven Sisters Story at Kuruala, 180 kilometres south west of Irrunytju, or Wingellina, which had been a really successful recording trip. So it was good to repeat that. It was interesting experience for me having a professional film crew coming along from CAAMA and… with producer Ivo Burum. And that put a different flavour to the recording expedition. And it was also good, Warwick Thornton being a cameraman on that. And he's gone on to great things since then and so on.

I suppose in a purist sense, I preferred the recording that had been done at Kuruala the previous year, that was entirely directed by the participants and by Simon and Pantjiti, and Noeli… Doing it again with a professional film crew, I had to….I got some amusement out of the set-ups for convoy shots and so on, and Ivo waving the cars past. And these were things that we just simply didn't bother with in the, in the pure form of recording the story and song and dance and landscape for Pitjantjatjara people. So it was sort of interesting that some of those conventions of documentary and so on were being applied on this second trip. But I think the actual recording of the story and the song and dance that followed were still, you know, true to that ethos that had been developed by Pitjantjatjara/Ngaanyatjarra Media, and was now being carried across into Ngaanyatjarra lands.

I believe they were happy with the representation of …what we were trying to do there in Ernabella and across the Pitjantjatjara/Ngaanyatjarra lands - and were certainly happy to be included in that bigger, national picture, because they were quite conscious of their pioneering role and ….the politics of representing that policy that Pitjantjatjara people had had worked up of representing themselves in, with modern media formats and… broadcast platforms.

I remember too, particularly scenes having my baby son on my arm in some of those shots. So, it's a nostalgic… for me. And yeah, I thought it was an important documentary to be made at the time. The issues around the use of the satellite were really quite critical to the…development of the remote media industry sector.

It was possibly really the last such recording trip that EVTV, Ernabella Video Television, or PY Media pulled off, really. We had already had a bit of a hiatus on the long running Seven Sisters recording project where we'd been on several cross-country trip several days at a time and covering segments of the song-line as it comes through the Pitjantjatjara lands. And our chairperson, who was a major figure and always played the elder sister in those recordings, had passed away. And so everything had gone quiet over at Ernabella, where I was based then. So it was really good to connect across to Ngaanyatjarra Lands, and to Noeli Roberts and Belle Davidson there at Irrunytju, and….sort of immediately following that shoot Irrunytju Media started up, and with our support from PY Media, ended up becoming Ngaanyatjarra Media and being incorporated into the national network of Remote Indigenous Media Organisations supporting communities in their area. So, it was quite an important moment, really, in their development that might have happened anyway. My main colleagues there at Ernabella, Simon Tjiyangu and Pantjiti, were already working over that way since 1986 and we'd started a little community TV station at Pipalyatjara in that year. So that handover of the concept of recording traditional song and dance through a video project was already there. But it certainly helped to have a repeat of that, that expedition further solidify that.

I think that was the beauty of the original concept of EVTV, of recording traditional song and dance on country, because that brought people together. I've already mentioned the dance festivals that flourished following that, right across the lands. So just the act of bringing people together was not just about telling that story, singing that song and doing that dance on that country. It meant people were sharing and… talking about the whole body, the whole canon of Pitjantjatjara song and dance and traditional knowledge. So it was a magic moment on the Satellite Dreaming shoot - everyone having come together from the Ngaanyatjarra side, as well as Simon and Pantjiti coming across - to revive that song from Ooldea, and perform the dance for it. And it's as much a mystery to me as it was to you, perhaps as to where it sprang from and how that came about. But… they told me that, you know, that hadn't been performed for 40 years. And often, you know, there are embargoes on songs when people pass away, or other people then come up with new variations on that. But for this old song to have been kind of revitalised just by people being together on a shoot, performing another dance and songline and yeah, it was one of those magical spinoffs.

Well, certainly, yeah, there was a whole separate cabinet for women's 'milmilpa' - secret sacred material - as well as for men's. And that was replicated with Irrunytju and Ngaanyatjarra Media - that was an important part of …wanting to use the media for their own purposes with no outside audience in mind. And, and that's still built into the work in Ngaanyatjarra Media and what was then Warlpiri Media - Pintupi Anmatjere Warlpiri Media and Communications as it is now - that they still have that cultural structure around access to material and that's being built into the archiving and so on. That's happening for PAW. It's not a real issue for our current work here in the Pilbara and Kimberley. We tend to only produce public material here, or if we do for women, say in Balgo, that material is given to them and kept by them, not by us. But yeah, it's still an important part of getting a foundation for traditional law and knowledge to be able to be passed to future generations.

I left PY Media in ‘96 to come across here to Broome and work for what was called the Pilbara and Kimberley BRACS Coordination Units, now Incorporated or since ‘98 incorporated ias Pilbara and Kimberley Aboriginal Media [PAKAM].

A lot happened for BRACS following the making of Satellite Dreaming…the Department of Aboriginal Affairs sent a couple of fellas out to do an audit and realised that, yes, a lot of the equipment was broken….most sites were not able to sustain local people in employment. There was no training available. And so, in ‘92, ‘93, the BRACS Revitalisation Strategy was born.

So, with the development of that revitalisation strategy, the Government needed to find bodies to give that funding to. There was no way they could dish it out community by community. It meant that the Australian remote media sector was kind of divvied up a bit like the colonial powers, and organisations were asked to step up to administer that money. For Pitjantjatjara/Ngaanyatjarra Media, it was obvious they were the body to receive that.

In this region, there was nobody really poised to take it on. There was a loose confederation of four major town stations in the Kimberley who'd been broadcasting courtesy of ABC AM services in their respective locations and sharing a bit of content for NAIDOC week and events like that. And that was called Kimberley Aboriginal Broadcasters Network. It seemed to be the body to take on that administrative role on behalf of the remote communities. At that time… it had a rotating secretariat, which that year was in Kununurra, but the ATSIC Regional Office in that region said, we don't want to deal with all this money without extra resources and funding, which is why I came over here to Broome. The Goolari region asked Broome Aboriginal Media Association if they would take it on, and that's how come I was then headhunted over breakfast at a national meeting to come from Pitjantjatjara lands and implement that revitalisation project here.

Generally, triennial funding is now secured for eight what are called RIMOs - Remote Indigenous Media Organisations - of which PAKAM is one. So BRACS …has not died: in a lot of regions it tended to become radio only. The focus of the funding was given primarily for radio. We had to argue strongly that we wanted to maintain the community television basis to BRACS and… prior to BRACS, the same ethos that had been developed up by EVTV and Warlpiri Media. And we've maintained that to this day. Ngaanyatjarra Media likewise still have a strong community television focus, as well as running radio. And the RIMOs these days all run satellite radio networks, so all the BRACS are connected up, and we run a model here where our network has fully contributed and primarily by our remote broadcast workers. We actually employ - currently 10 or so, but up to 20 in a year - part time community media workers in the region.

We're probably the biggest employer of the RIMOs, but…and of course, with the change in technology and digital video production, it's a lot cheaper and a lot easier to train people to produce video. With the development of the ICTV satellite service, which we managed to pull off as a collective effort, we had a …we've had national remote indigenous media festival, 18 of them now that used to run every year and now it's every second year.

Those have been great opportunities for the whole sector to get together, have sort of focus training on different aspects of media production that they don't get at home in the general course of events, and to network and build the tnational sector body, which was called Indigenous Remote Communications Australia or IRCA, and that's now in the last couple of years, become the national peak body for all of the indigenous media sector with the name change to First Nations Media Australia.

So in 2001, at the third remote BRACS Video Festival - as they were called then - we were made aware that the digital conversion was going to be coming in about 10 years time. And our advice from the chief engineer at Imparja, Tim Mason, was that it would be just too expensive to try and run digital television services in the remote communities. So, we realised from that point that we needed to start work already on developing up an alternative delivery platform to the local community TV services in the BRACS. And at that meeting, the idea was formed to utilise a second part time channel that Imparja had that they used just to send higher quality sports content and so on across to the satellite uplink.

The four Bush organisations there - PY Media, Warlpiri Media, Ngaanyatjarra Media and PAKAM - agreed to start feeding content to Imparja to put up on that service. We'd already run a couple of tests as early as ’98, and verified that yeah, the service could carry television content and be received in all parts of the country. And so, we started up slowly. It started essentially on weekends. PY Media were broadcasting the Central Australian Footy League back to their communities through this channel. And when the football game finished, there would be two or three hours of video content that we had sent in to Imparja, who would ingest it and put it up. So that's …what became ICTV - Indigenous Community Television - started right back there from 2000, 2001, when we decided to get organised and start trying to feed that and build it towards a full time channel - so that when the digital conversion came, we would have a platform that we could still get community TV content back to our remote viewers. So that built up and built up, and became quite successful to the point in 2006, we were running 22 hours of content a day. Imparja were a little bit reluctant to give us full run on the channel because they saw the political power of it, in the context of the development of the NITV - National Indigenous Television Service. So, I was on the NITV Working Group for two and a half years prior to the establishment of NITV - attempting to represent the interests of the remote sector and IRCA, and to maintain that platform that we had developed into the new national service. And we had a roll out – it was called the RIBS TV roll out.

…and rolled it way beyond the original 80 BRACS, to 153 sites across the country. So, we had established a strong transmission platform, and this was the very platform that NITV was then mandated by government to take over.

And in the end, they chose to fund a new NITV company - but on the basis that it built on the platform that ICTV had created. So in the NITV business plan, there was talk about, well, you know, with the 12 million a year, we can really only fund four hours a day of NITV content, and that might get repeated. So, there will be room for perhaps for four hours a day of looser formatting of community content, and still carry, you know, some of that ICTV service. Unfortunately, that was not to be…

Basically we had to compete with other, more professional and commercially based video producers for commissioning dollars, which put us through a lot of hoops and paperwork and so on. We had to provide content to television 1/2 hours or quarter hours instead of our loose formatting of any duration goes, and… rolling it all together. And so, in effect, it really didn't happen. And we ended up with our transmission platform being taken over by a national service. People in the remote communities felt quite gipped by that - there were comments from Noeli and Belle on it like, you know, “we don't want to see all these sad stories, that…sort of Stolen Generation stories from the Eastern states. We want to see our own stories in language”.

However, all that got resolved, thank goodness, with the transfer of the NITV service to SBS, and I think perhaps, Government realising that there might be backlash on the cutting out of spectrum for community television, generously offered a subsidy for a full satellite channel which was still being run out of Imparja until July this year, where ICTV have now taken over their own playout and are funded fully for the service, including the satellite uplink costs. So at last we had the full time channel back and we haven't looked back since.

And with the digital conversion and the the opportunity to finally get a full time satellite channel, that original dream of Ernabella Video Television, where… we have a recording of a meeting that CAAMA held before the launch of the AUSSAT satellite right back in 1984, where one of our committee elders was saying, ‘we don't want that satellite, we want our own satellite’. Well, little did he know that that has actually come to fruition and that, yes, the remote indigenous community television sector have their own satellite channel and …it's opened up a lot more now, it's not just BRACS and the RIMOs who are contributing content. There are lots of organisations, art centres, ranger groups, … other sort of organisations, Barkly Regional Arts and so on, First Languages, Australia, who are all contributing content to that satellite service.

And we're hoping that we can sustain an ICTV service on the VAST satellite beyond the next five years. However, we're having to, ICTV are conducting a feasibility study into how we might transition that service in the future and all the implications of that. So, the “satellite dreaming” may very well come to an end at some point in the not too distant future. But we're confident that we'll always find ways to share that content around online…

And with our archive platforms also being worked up and developed, we're confident that we'll be able to get remote community television content back to our remote audiences one way or another into the future.

So, the other thing you asked was particularly about Seven Sisters and what's happened with Seven Sisters recording since those days. And there's been a major exhibition at the Australian National Museum for Seven Sisters. I was approached and sort of provided information about those early EVTV recordings….

We've recorded stories over here in WA, south of Balgo, for The Nakarra Nakarra, as they're called here, and Seven Sisters sites there. And there have been other songlines, too, most notably the…Two Women story that comes up sort of close to Kuruala, there from the south all the way through Ngaanyatjarra Lands, past Irrunytju and all the way up to Docker River. And then I believe even, you know, spins around, comes down towards - and I'm not sure where it goes from there. But Ngaanyatjarra Media produced two similar documentary recordings on that story, a decade apart. I was present for both of them and sort of helped project manage the second one. The first one was actually part of the National Indigenous Documentary Fund that started up in ‘97. And PAKAM had one of those original ones, too. It wasn't broadcast in its pure form on SBS, so it would have been the following year, I think ‘98. They sent out a crew to sort of do some pickup interviews and …cut it down and insert some shots of tumbleweed blowing in the wind and things like that, to jazz it up for a mainstream audience. But nevertheless, it helped fund that original recording. And then 10 years later, the custodians who had given us that song, and on that first recording had passed, and Noeli himself dreamt a whole new series of verses for the songline. And so we repeated a part of that and carried it on further to the north with a whole, whole new… So it was very interesting that, you know, a story that's been around for millennia is kept going … with, you know, similar song structure and so on, you know, I’m no pure ethnomusicologist, but with changes of verses and personnel, of course. And then that took us all the way up towards Docker River. And since then, Central Land Council have recorded another leg of that, I believe, with Pantjiti’s input there as well. So that's another travelling song line, you know, comes right up from the coast down near Yalata somewhere, or from the west, actually. Two sisters travelling, the younger one always wanted to go back home where she's grown up, but the older one persuading her to keep going back to their ancestral country. And there was a beautiful parallel in that with Pantjiti and her half sister, Belle, who had been brought up in Warburton mission and who Pantjiti was passing over that, I guess… cultural custodianship and video recording there, and lovely stories …how they would go and bring Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara from the West there, women in, and view old EVTV recordings to revitalise those dances over in the West. So, yeah, Seven Sisters has now been recorded in quite a few other locations besides the Pitjantjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra lands, and amalgamated into that. And there's a huge art movement now which wasn't really going in the Pitjantjatjara lands at the time you were there for Satellite Dreaming, and there are major artworks being produced by Tjala Arts from Amata and so on - huge canvases of Seven Sisters that are just stunning artworks. So it's getting expression and in other forms of media as well, besides video.

The recording of traditional song and dance on country that was pioneered back there in the mid 80s by Ernabella Video Television is, in my view, vital cultural work; that body of work then forms a part of a priceless cultural heritage for all of Australia. My concern is that it's already too late for a lot of that body of knowledge that was around on this continent for millennia is already lost, and it's being lost daily as senior people pass away. And these stories haven't been recorded.

But to have had the privilege of helping people record that living body of knowledge has been an important part of my life. This has been realised, and there have been some funding initiatives to try and really build that sort of work. So, Screen Australia have had two Songlines on Screen series that were, you know, engineered by Rachel Perkins and Erica Glynn – notably, which sought to give some redress to that. And PAKAM have recorded two stories for that initiative from series 1 and series 2. One of them is Tjawa Tjawa, south of Balgo, a group of women who had come across from the west, from Roebourne looking for husbands and travelling through country there before they went underground back to their home. And the other story was a - it's called Niminjarra, about two snakes, 'Jila Kujarra', travelling from the east across to Lake Dora near Punmu, and ..the hunters who were following them, and the cataclysmic coming together there at Lake Dora, where the snakes went down into the ground and formed the whole aquifer water body between there and the Fitzroy. And so, there were, I think, eight in each series from around the country. And they were high budget for 10, 12 minute documentaries with a budget of $180,000, totally different scale of operation to our Seven Sisters recordings of hours of content and no money… and people were chipping in to get enough fuel and water and food to travel in their beaten-up vehicles and so on. But at least there was that recognition of the critical cultural importance of that work.

I would love to see much more of it. But… community television is now covering all sorts of areas and a lot of oral history, Bush foods, sports, cultural events. Music is huge, of course. So … the pure focus of Ernabella Video Television is … now being kind of dissipated in a lot of different genres and formats, I suppose. But it is still the work that is closest to my heart. PAKAM records the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre, biennial AGM and dance festivals; we record the annual Mowanjum Dance Festival, and various art centres who put on dance performance events. So, we're there to record everything that's happening in this region in the way of traditional song and dance and and being able to distribute it a lot more widely than EVTV was, just through the sale of VHS tapes back then, and being able to even do these sorts of events live on ICTV into the future and so on. So, yeah, so we're still there, still carrying on that work. And I just hope that we can get as much of it recorded and… maintained and open for community access for that huge wealth of cultural tradition to be carried into the future.