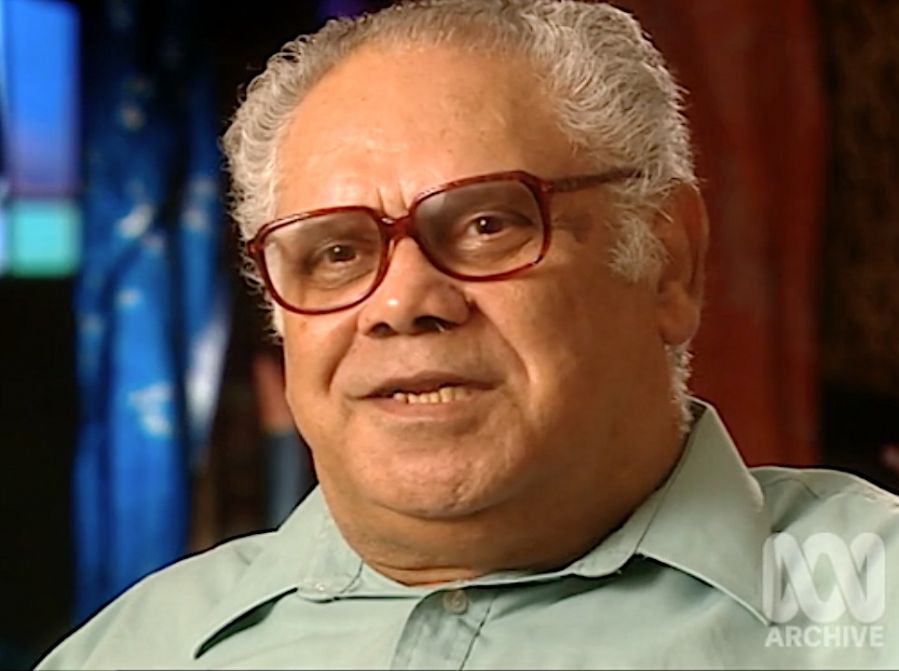

Lester Bostock

‘A lot more have come through…’ & ‘Aboriginal thought needs to be part of the mainstream…’

I was one of the producers of Lousy Little Sixpence. I was still at SBS, spent a lot of time talking to management and SBS about getting a television programme together. SBS asked me to do a feasibility study on Aboriginal needs for television. That feasibility study became the The Greater Perspective, which was the guideline, mainly the guideline for people who work in Aboriginal communities.

[Film clip: ‘So we're all here for public television, seems I've been down this road…’] SBS was able to get some funding to train a lot of people in television and my, my big thing at that time was getting Aboriginal people behind the camera. That was when we turned up at Metro Screen: so the Metro Screen, jumped at the opportunity to have a film training programme.

I just kept on doing things and getting things done, and taking up new challenges, and using a lot of the stuff I'd written for Greater Perspective, and wrote into the film training programme, and that is now the guidelines for a lot of filmmakers who work with Aboriginal people, the codes of conduct, when we're working in communities.

There's more and more Blackfellas on television. There's a lot of them… are behind the camera. A lot more have come through. And that's good because I remember back in back in the 70s, there was only a handful.

Lester Bostock, interviewed in 'Best Foot Forward'

'Aboriginal thought needs to be part of the mainstream…'

Childhood:

I was born at Coraki in northern New South Wales, at the Box Ridge Aboriginal Mission Station there. My early schooling was at the mission school. One of my vivid memories of that is being lined up every, every morning - all of us kids being lined up and made to take a tablespoonful of cod liver oil every morning, and before we went into the class. And then every morning all the kids heads were checked for lice… but the cod liver oil one, I haven't eaten…I haven't had cod liver oil since then. I hate cod liver oil.

I'm the eldest. And being the eldest male, the responsibility of looking after the others was very much my responsibility. I remember the times when we were kids going to school and we had to walk about five or six hundred yards to get water - for drinking and for washing. And when we washed, all the kids shared the one, one tub of water. And being the eldest, I was the last in the tub.

When we moved to Brisbane, big gangs of white kids used to chase me around the school. You had to fight and fight. You had to learn to use your fists or a stick, or anything that came in… So after a few days of this, what I'd done, I had a big lump of 4x2 that I'd found and I hid it in the grass. And so, when the kids chased me, I raced to that lump of grass and pulled out this 4x2, and started hitting into them with it… I was about 11, 12 at the time.

My mum, she died about four or five months ago and she was in her early nineties then. And so, she kept the family together. She was a very strong woman. You minded your P’s and Q’s around her. She was tender but strict. Those women had to be really strong at that time to hold things together, because remember, that was the height of the Aboriginal Protection Act and things were very tight. You just weren't allowed into the towns and things like that. And certain shops wouldn't serve you, and certain shops, would… I remember when I was about 18, 19, I went up to central Queensland looking for work. Because of course, I was a stranger in the town, the police, the local police, they saw all the people getting out of the bus. They said, ‘You, come here. I want you out of town… If you don't have a job by the end of today I want you out of town or you go in…

When we move from Tweed to Brisbane in 1944, ‘45, first we moved into the Bush camps in Brisbane. There was a whole lot of Aboriginal families and Island families living in humpies in the shantytown outside of Brisbane at Morvale. Growing up at Rocklea in teenage, my teenage years, we'd all broken up into gangs. The Aboriginal and the migrant kids generally hung around together.

I remember one year, I think it was 1956, I got the best and fairest player for that year and they gave me a trophy of a little football I've still got that…

Having a Disability

It was either from the playing of the football or the job I was working at at the time - I'd got a bump on the shin and then gangrene set in, and they thought they might have been able to save the leg, but what happened was the bone on the shin had just eaten away with a cancerous growth and they took the leg off really high up, in my thighs. I became more inward, kept a lot of those things within me and … So I just took a lot, it took about 10 years really, to really start to come to terms with it, with a lot of that. I had relationships with girlfriends and things like that at the time, and I've always had that feeling that having the disability had an effect on the relationships.

Tranby College, politics & theatre

I got involved with Tranby. Tranby at the time was a live in college, so I moved in there and did a course there, and I did a bookkeeping course and learnt a bit about administrations. And a lot of the organising for the Referendum was held at Tranby. You were rubbing shoulders with a lot of the very radical people of that era. They used to hold things called ‘silent vigils’ in those days, and we'd go and hand out pamphlets, hold up placards and things like that, outside government houses. So, there was Faith Bandler, myself, Kath Walker, Jack Davis, Charlie Perkins - all of those people there. And I used to hobble along, and into all those things.

And there was a lot of street action and I was involved in a lot of that. There was a big moratorium that was held outside the Sydney Town Hall. There were 10, probably 10,000 people which blocked off the whole of that Sydney Town Hall area. Just after that, the Embassy happened with Billy Craigie and a few of the others.

We’d spent a lot of our time supporting the Embassy, then about ’71, ’70, ‘71, I left Tranby and got involved with the little theatre group that was starting in Redfern. We saw at that time, we saw theatre as a means of publicising our cause. It was a means of letting people know that we're not all raving …street politicians who are raving ratbags, but we have other things to offer.

Now, it's been 30 years since we had the building in Redfern, but the people in Redfern still regard that site where that building is as the Black Theatre building. It's our building. It's our site. My direction is still continuing on with that, with that empowering of people.

Filmmaking & film training

I tend to reinvent myself about every 10 years. The early 1980s, I also took some time off from SBS to work on a documentary which was Lousy Little Sixpence, and I was one of the producers on that. Because we had a bit of knowledge we would be working on those programmes. So those types of things came about not because one had a desire to pursue some sort of career, but one reacted to what the situation was at the time. It reminded me a lot of my childhood. I remember at Box Ridge, at Coraki, when any white strangers used to come up in cars and suits, my mother and all the older people would send us kids up into the bush to hide because they knew that only government people would come to the reserve.

But I was producing, my brother Gerry was directing. You could count them all on one hand, the number of film and television makers around at that time in 1990, and that's not too long ago. The only way we're going to get Aboriginal crews is train them ourselves. So, I went and saw some filmmaker friends of mine, run into Tom Jeffries, who was then head of the Film School. What was produced out of those two courses was about, 30 Aboriginal people came out of those two courses. Of that 30 I know of about 12 to 15, are still working in the industry somewhere. And that's developing a foundation. A lot of them go do work for the ABC now, a lot of them, they work for SBS, a couple have gone on to Channel Nine. Some have gone back to their community and started making videos within their own communities. To me, you don't if you don't see people around, you haven't really lost them. You've given them some skills - once you've given people some skills they’re never the same again. I feel really proud of those people because I … to me, they are my children. And so they …they gone on to do things, but one of my one of my dreams is to develop an Aboriginal genre of filmmaking. We haven't got there yet, but we're getting there slowly.

What we have to fight about now

What we have to fight about now is not so much the economics of colonialism, but the colonialism of the mind, where Aboriginal thought needs to be part of the mainstream thought and must be accepted as such. So, it's a, it's a thing that I … a philosophy that I've had …sort of empowering people, making people equal, and getting people to understand each other from both sides.

[Transcript of extracts from ‘Message Stick: Best Foot Forward’ – Rima Tamou, ABC (2003)]