Why First Nations Media Matters

My journey in the First Nations media industry 2001-2020, by Daniel Featherstone

All photographs by Daniel Featherstone unless credited. Some photos include images of deceased people.

My awareness of Australia’s emerging Indigenous media sector began in Perth in 1990 while researching an essay on the development of Aboriginal film and television within media studies at Curtin University. I watched films by Aboriginal filmmakers of the 1970-80s and read about the emergence of Radio Redfern in Sydney and Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) in Alice Springs and the cultural impact debates sparked by the AUSSAT satellite in the early 1980s. I was inspired by Eric Michaels’ The Aboriginal Invention of Television (Michaels, 1986), the pirate TV broadcasts in Yuendumu and Ernabella in the early 1980s, the ‘Out of the Silent Land’ report (Willmot 1984) which led to the establishment of the Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme (BRACS), and CAAMA’s ‘David and Goliath’ battle to establish Imparja television.

Having grown up in Geraldton WA in the 1970s-80s, I was aware of the racism my Yamatji friends experienced. I now began to see how systemic the racism and negative representation was in WA’s mainstream media, with Aboriginal people and ‘issues’ portrayed through a white lens with very few Aboriginal voices.

I considered following the pathway of the 1980s documentary filmmakers who had collaborated with Aboriginal people and communities to tell their stories in their own voice, including Ansara, Noakes, Morgan, and Cavadini and Strachan. However, with emerging Aboriginal filmmakers and broadcasters calling for the tools and resources to enable self-representation, I concluded the way forward for non-Indigenous filmmakers was to hand over the camera and support this process of change. Not seeing any immediate role, I focused on developing my film-making craft through making short films and documentaries, camera assisting on TV series, and helping establish community television in Perth in the early 1990s.

I moved to Sydney in 1995 to study cinematography at the Australian, Film, TV and Radio School (AFTRS). During my three years at AFTRS I was very fortunate to study alongside many of Australia’s highly talented First Nations film-makers including Ivan Sen, Warwick Thornton, Rachel Perkins, Catriona McKenzie, Erica Glynn, Romaine Moreton, Steven McGregor and cinematographers Allan Collins and Murray Lui. The AFTRS training opportunities were part of a deliberate Indigenous film industry development strategy led by numerous trailblazers including Walter Saunders and Lester Bostock, with a dedicated Indigenous unit established within the Australian Film Commission. The impact of this work is evident, with this cohort going on to revolutionise the Australian film and television industry, telling an incredible range of stories across all genres and winning dozens of national and international awards.

However, I always felt that more support was needed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote communities to document their life stories and rich cultural knowledge and contribute to the national dialogue and identity.

Having left AFTRS and worked as a cinematographer in Sydney for four years, I began to feel jaded by the commercial and superficial nature of the industry. Where were the real stories from the heart? In 2001, I applied for the role of Media Coordinator at Ngaanyatjarra Media, a small remote Indigenous media organisation (RIMO) supporting 12 communities in the spectacular Western Desert region of Western Australia spanning about 400,000 square kilometres.

The remote community of Irrunytju (Wingellina) community, 10km from the tri-state border of WA, SA and NT.

I headed out to Irrunytju (Wingellina) community as Ngaanyatjarra Media’s only full-time non-Indigenous staff member. I was nervous but excited about the prospect of supporting Yarnangu (Ngaanyatjarra people) to make their own radio and television and learning more about the Aboriginal culture and history in my home state. It was September 2001 and the terrorist attack on New York’s twin towers had just changed the world. The Howard Government was ramping up its rhetoric on national security, turning back boats and targeting welfare dependency in the leadup to a November election. I was glad to be heading to the desert.

Ngaanyatjarra Media was the most recently established of the eight RIMOs across central and northern Australia. Originally established as Irrunytju Media in 1992, it was led by Belle Karirrka Davidson and Noeli Mantjantja Roberts, along with radio broadcasters Simon and Roma Butler, with the primary aim of keeping language and culture strong.

Noeli and Belle had worked on a number of cultural video productions with Ernabella Video and TV (EVTV) workers Simon Tjiyangu (deceased) and Pantjiti McKenzie (Belle’s sister) and coordinator Neil Turner. This included the 1990 production Tjukurpa Kungkarrangkalpatjara, a re-enactment of the Seven Sisters story at Kuruala (one of a series tracking the songline across the APY region) and the Satellite Dreaming version in 1991.

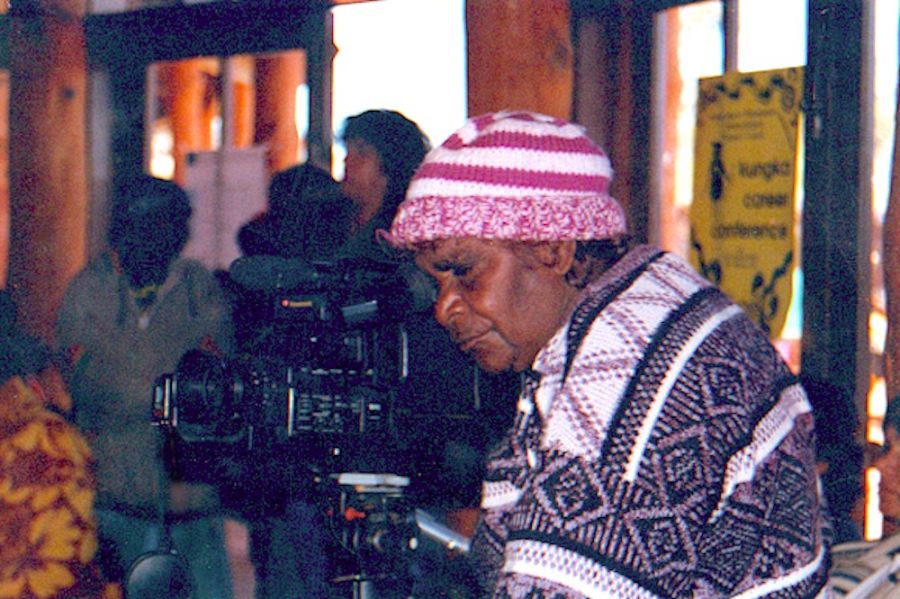

Belle Davidson filming the Kungka Career Conference 1999 (Photo: Irrunytju Media)

Keen to expand the EVTV cultural production model to the Ngaanyatjarra region, Noeli and Belle went on to organise and document Turlku (traditional dance) events and Tjukurrpa (Law/songlines) re-enactments and distribute the tapes for local broadcast and viewing throughout the 1990s. Noeli and Belle, like many Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people of their age, had been removed from their custodial homelands as children during the 1950s to clear the region for the British nuclear and long-range rocket tests. Belle was taken west to Warburton mission, Noeli east to Ernabella mission. They returned to their country as part of the ‘homeland movement’ in the mid 1970s.

As Irrunytju Media began documenting social and cultural activities across the region, other communities expressed interest in setting up their own media programs. From 1993 to 1996, eleven more Ngaanyatjarra communities set up BRACS facilities under the BRACS Revitalisation Program, with Irrunytju Media becoming the regional coordination hub, or RIMO, delivering training and production support for all 12. In 1998, Irrunytju Media became Ngaanyatjarra Media to reflect this regional role, with its coordination transferred from Irrunytju Community to regional land council Ngaanyatjarra Council. That year, neighbouring Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (PY) Media invited Ngaanyatjarra communities to join a cross-regional 5NPY radio network.

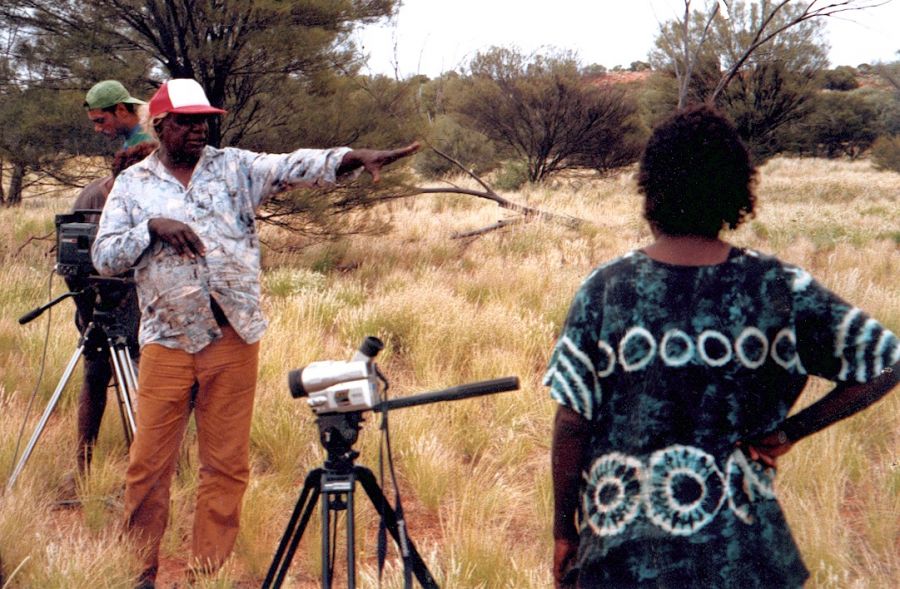

Noeli Roberts during the filming of the Minyma Kutjara Tjukurrpa (Two Sisters Story) 1998 (Photo: Irrunytju Media)

In 1999, Irrunytju Media completed a major production Minyma Tjukurrpa (Two Sisters Story), a songline about two sisters’ northward journey from the Nullarbor plains towards Irrunytju, which screened on Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) and won Best Cultural Documentary at the 2000 Tudawali Film and Television Awards.

However, when I arrived at Ngaanyatjarra Media, there had been no full-time Coordinator for a year and little media production or local broadcasting was happening across the region. With only a single funded staff position, I began to realise the enormity of the task ahead. My AFTRS training and film industry experience had not prepared me for managing a remote Indigenous media organisation. With only a few words of Ngaanyatjarra language, I couldn’t understand what people were saying. I had to unlearn my walypala (whitefella) thinking and start re-learning within a Yarnangu worldview - a humbling but rewarding experience. Fortunately my two wonderful malpas (co-workers/friends) helped guide me on the journey – learning about Yarnangu media practice, culture and language and most importantly, how to stop talking and listen. As my name was the same as a deceased person, Noeli re-named me ‘Utjutja’, which is how I was known locally for the next 9 years.

My trial by fire into the Indigenous media sector began at a national meeting in Rockhampton in September 2001, hosted by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and peak body National Indigenous Media Association of Australia (NIMAA), to discuss the proposal to establish a National Indigenous Broadcasting Service (NIBS). I met many of the key players from the national and remote media sectors.

Daniel (Utjutja) in the Ngaanyatjarra Media office 2002

Over the next two days, I witnessed the collapse of NIMAA and the fiery debate over the proposed options for establishing a NIBS - a “black SBS”- an ambition of the sector since the 1980s. Clearly the sector was full of passion, politics and strong personalities. I met Neil Turner from Pilbara and Kimberley Aboriginal Media (PAKAM; formerly at EVTV/ PY Media), Will Rogers from PY Media, Rita Cattoni from Warlpiri Media and former BRACS Working Party coordinator at NIMAA Russell Bomford, and was welcomed into the remote media sector.

Shortly after arriving at Irrunytju, I attended the third Remote Video Festival hosted by PY Media at Umuwa in November 2001 along with 8 media students enrolled in BRACS training with Batchelor Institute. BRACS broadcasters and media producers converged from across Australia for the inspiring week-long event. I felt honoured to meet remote media pioneers Francis Jupurrurla Kelly from Warlpiri Media, Simon Tjiyangu and Pantjiti McKenzie from PY Media (formerly EVTV) and many more. Each night we watched powerful Inma (cultural dance) performances and outdoor video screenings before sleeping in swags under the stars.

A key topic of discussion was the formation of a new remote media peak body, given the recent demise of NIMAA. Indigenous Remote Communications Association (IRCA) was established soon after with Russell Bomford as part-time Manager and industry pioneer Bill Thaiday as Chairperson. Also, Imparja’s Chief Engineer Tim Mason invited us to utilise Imparja’s second satellite channel 31 to share remote community content across the country, building on a 1998 remote broadcast trial. Indigenous Community Television (ICTV) grew from this initial conversation (see ICTV section below).

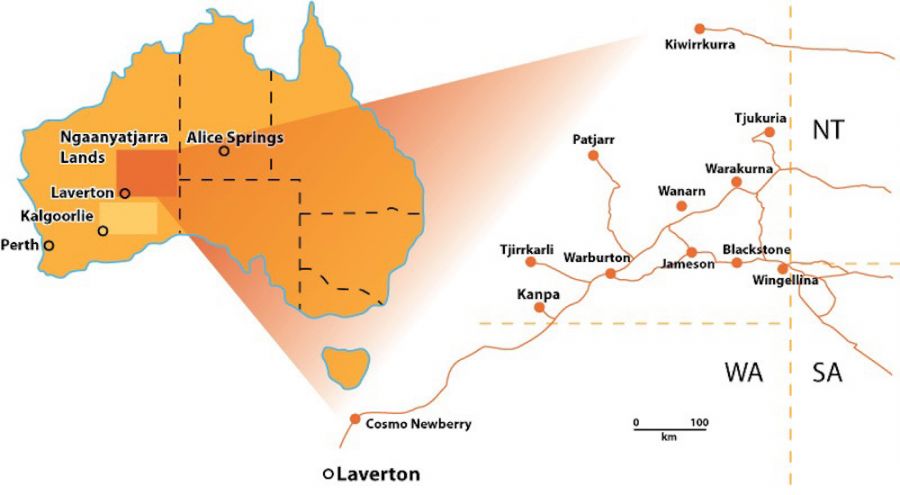

Ngaanyatjarra Media now supports the 12 communities in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands plus Tjuntjuntjara and Mt Margaret to the south.

Returning with renewed enthusiasm, Noeli Roberts and I visited the 12 Ngaanyatjarra BRACS communities to outline the services that Ngaanyatjarra Media could provide - radio broadcasting, video production, media training and supporting BRACS workers- and hear what people wanted. There was strong Yarnangu interest in Ngaanyatjarra Media with requests for more training and support for workers, technical repairs, a dedicated Ngaanyatjarra radio network, more video production and cultural activities and so on. However, some people simply wanted a phone in their home.

We found little community staff interest in supporting the BRACS program beyond keeping the ABC services working. In several communities, BRACS facilities were in disarray or transmission equipment not working. We met some people enrolled in BRACS training through Batchelor College but found little sign of local broadcasting or video production underway. The self-motivated cultural media activity that Michaels had described was either a fiction or specific to a time and place. However, this self-reliance was embedded into the BRACS funding model. With limited resources, RIMOs were tasked with providing hub and spoke support to BRACS sites across vast regions - a model seemingly set up to fail. Nonetheless, with strong Yarnangu support, we were determined to give it our best shot.

From 2002, the small media team worked hard to ‘grow up’ Ngaanyatjarra Media. With intermittent assistance from my partner at the time, Indigenous Fijian broadcaster and film-maker Valerie Bichard, we established training programs and began producing a regular Ngaanyatjarra Radio Show on the 5NPY radio network and a slate of community and corporate video productions.

Simon and Roma Butler broadcasting the Ngaanyatjarra Radio Show from the Irrunytju radio studio 2002.

With BRACS studios only set up for local broadcasting, broadcasters sent minidisks of their programs by mail plane to Irrunytju for playout on the 5NPY regional satellite network. However, the Ngaanyatjarra Radio Show soon became very popular with Yarnangu audiences. With only one-hour daily timeslots available on 5NPY, it became clear that we needed a dedicated Ngaanyatjarra Radio network, however without spare satellite capacity this took several years to achieve.

In order to improve training retention and outcomes, we negotiated with Batchelor Institute’s Indigenous Media Unit to co-deliver the BRACS training on country, combining coursework with hands-on broadcasting and video production. This greatly improved attendance and graduation levels, with tangible production outcomes and direct community feedback.

By 2004, a core group of about 20 trainees from 8 communities became Ngaanyatjarra Media’s team of broadcasters and media workers over the years ahead. Video crews would regularly drive hundreds of kilometres to film football games, music nights, meetings or community events, with quickly edited videos distributed to communities to play over the BRACS TV broadcast.

Incorporation meeting at Walu homeland, November 2002.

While radio was the primary activity for some RIMOs, Ngaanyatjarra Media had developed with a video and cultural focus. In response to community interest, it was now becoming a multi-media hub, incorporating radio, video production, computer access and IT skills, music development, technical support and media training. Yet all of this was being done from three rooms at the back of the Irrunytju community office. We needed a dedicated facility.

With interest and support growing, we organised an event at Walu homeland in 2002 to celebrate Ngaanyatjarra Media’s 10th anniversary and to separately incorporate the organisation (previously under Ngaanyatjarra Council). Over 400 people attended the three days of meetings, nightly video screenings, daily Turlku performances and a band night staged on a flat-bed truck, powered by a small generator. Members voted for the first Media Committee, with representatives from the 12 communities (later grew to 14), and a Minyma (female) and Wati (male) chairperson.Being separately incorporated enabled Ngaanyatjarra Media to seek funding to expand its activities. Ngaanyatjarra Media could now begin to grow up.

In 2003, the newly formed Ngaanyatjarra Media Board developed its first Strategic Plan. This highly ambitious 3-year plan set out to build a regional media and communications centre in Irrunytju, establish a Ngaanyatjarra radio network, upgrade BRACS media centres, improve regional telecommunications and internet access, develop training and employment opportunities, support language and cultural maintenance, and develop effective governance and management.

Rhys Winter interviews Daisy Ward at the Ngaanyatjarra Native Title handover ceremony at Parntirrpi homeland, June 2005, Hayden Scott on camera.

With my limited fundraising, technical and governance experience, this was a very daunting list. However, with a clear Yiwara (path) laid out and through strong community support and partnerships with regional and state agencies, we set about implementing the bold plan.

The next few years were very busy. We continued developing the Ngaanyatjarra radio program, delivering media training, and filming regional events, including the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Native Title Determination in June 2005. Meanwhile we established a technical services unit, began delivering regional IT training, and started planning and fundraising for the new media and communications centre.

Over the next five years, we gradually built Ngaanyatjarra Media’s regional role to deliver programs spanning radio, video production, IT, training, music development, cultural projects, events and technical services.

Following the incorporation event at Walu, there were requests by elders for Ngaanyatjarra Media to organise regular Turlku events. Community bands also requested more music events.

Minyma performing Turlku at first Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja, Mantamaru 2003.

With six weeks lead time, we organised the first two-day Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja (Ngaanyatjarra Music and Culture Festival) at Mantamaru (Jameson) community in October 2003. Despite dust and wind, a large crowd turned up for the dusk Turlku performance, followed by a ‘Battle of the Bands’ on a makeshift dirt stage that went long into the night.

We staged the whole event with borrowed equipment, patched together by new Radio Trainer Ananth Siluvaimichael. The media workers filmed the event which we edited into a popular video and audiorecording for radio.

Nanta Brown producing a new song by Irrunytju's Alyuntjuru Band, 2009.

The Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja went on to become an annual event, hosted in a different community each year. It led to demand for Ngaanyatjarra Media to help community bands record their music. Given Ananth’s music production experience, we purchased a basic recording system and produced a compilation album Turlku 1. This began a new stream of activity in music recording and training, including production of several more CDs and Garageband recording workshops, enabling Yarnangu to produce their own music. In 2006 we wrote a Ngaanyatjarra Music Development Strategy which led to the funding of a three-year Music Development program from 2006-8, and future music programs.

With strong community interest in the new Ara Irititja (old days stories) archive computer and accessing Ngaanyatjarra Media’s growing collection of digital photographs, music and videos, we needed a dedicated space for community access local content and develop IT skills.

IT Trainer Pete Graham and community members in the Irrunytju telecentre, 2004.

We successfully applied to set up a telecentre in Irrunytju in late 2003 and recruited an IT trainer. The facility received constant use by people of all ages as well as visitors from other communities. With only 1GB monthly download limit, we focused training on offline applications such as digital photography and artwork and accessing local content from the server. The videoconferencing facility was regularly used by families to connect with relatives in prison or hospital up to 2000 km away.

Word soon spread and demand grew for similar IT facilities in other communities. In 2005, we successfully applied for TAPRIC funding to run a Ngaanyatjarra IT training and support program. Without ongoing computer access the training would have little lasting effect, so we set up basic e-centres with donated computers in the 14 communities, mostly collocated with the RIBS facility.

Family looking at Ara Irititja archive as part of IT training in Warakurna 2006

Former teachers Steve Grace and Sasha Myler delivered roving training and support over the next 18 months. We trained local Yarnangu coordinators in each community to run the facility and provide local support. With no internet access in most communities, initial training focused on offline applications and digital media skills. We also employed a technician to set up the IT facilities and maintain the satellite and broadcast equipment in each community.

With no internet access in most communities, we focused the initial IT training on offline applications and digital media skills – MS Word, digital photography, Garageband music recording, video production, digital artwork, internet banking and the Ara Irititja archive. As computer use increased in schools and workplaces, demand for the training grew, leading to other IT training projects over future years and upgraded online e-centres.

Having IRCA as a peak body helped the remote sector become more coordinated during the 2000s.

AICA conference, September 2003: (L-R) Ella Geia (TEABBA), Selena Sullivan (ABC), Florence Onus (TAIMA, standing), Belle Davidson (Ngaanyatjarra Media) and Simon Fisher (PAW Media).

This resulted in funding for several sector-wide projects including the 2005 ICTV transmitter rollout and the Indigenous Remote Radio Renewal program in 2006, the first national studio and broadcast equipment upgrade since the BRACS Revitalisation Strategy.

However, the national Indigenous media sector had been without a peak body since 2001. In May 2003, a national meeting was called in Sydney to establish Australian Indigenous Communications Association (AICA), the third national peak body after National Aboriginal and Islander Broadcasting Association (NAIBA, 1982-85) and National Indigenous Media Association of Australia (NIMAA, 1992- 2001). AICA’s main outcome was its annual conference, which provided an opportunity for Indigenous media representatives from around to country to network, share their experience and participate in sector planning and policy discussions. However, with limited resources and factional politics brewing, AICA struggled to build on the progress achieved in the 1990s.

Following the 2001 Umuwa festival, PY Media began weekend satellite broadcasts of football games and compiled videos from the Remote Video festival. This grew in 2002, with PY Media, Pilbara and Kimberley Aboriginal Media (PAKAM), Warlpiri Media and Ngaanyatjarra Media all sending tapes or hard drives to Imparja for ingest and playout. A regular 3-hour program called “IRCA in Action” was started in 2003, featuring a mixed bag of local festivals and events, sports carnivals, cultural dance performances, meetings, bush trips, training videos, health and educational promotions, school trips, and music videos. This was the beginning of Indigenous Community Television (ICTV).

Meeting held at Ellery Creek Big Hole in 2004 to plan ICTV expansion

Programming steadily increased to a daily 8-hour program (9am and 5pm) by 2005, with content streamed to Imparja from a simple playout computer managed by PY Media.

However, most communities did not have a dedicated ICTV television transmitter. After lobbying from IRCA, DCITA provided $2million in 2005, enabling the installation of dedicated ICTV transmitters in 147 Remote Indigenous Broadcasting Services (RIBS, formerly BRACS) communities and a few regional towns including Alice Springs, with the rollout completed by early 2007.

There was overwhelming support for the dedicated ICTV service, sparking a resurgence in remote video production. By 2006, up to 20 hours of new content was contributed monthly from over 70 communities in about 25 languages. Despite repeated programming and varied production values, ICTV became the preferred TV service across remote Australia.

Keith 'Joog' Lethbridge, unknown, Francis Kelly, Patsy Mudgedell, Jack Cook, Geoffrey West (behind) and Milton Hansen at the inaugural ICTV AGM in Balgo 2006

ICTV was incorporated in 2006 with its inaugural AGM at the 6th National Remote Indigenous Media Festival in Balgo WA, hosted by PAKAM. Having run without funding for 5 years, ICTV received its first grant of $75,000 in 2006 and employed Rita Cattoni (formerly PAW Media Manager) as part-time Manager. ICTV’s channel 31 was made open access on the satellite, drawing positive feedback from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous viewers.

However two significant policy changes were about to cut ICTV’s growth short. The first was the removal of funding support for remote video production under a 2006 DCITA review of the Indigenous Broadcasting Program (IBP), which reduced the scope of IBP funding to radio broadcasting only. After nearly two decades of BRACS community television and, at a time of increasing convergence of broadcasting with on-line and mobile platforms, this was a major backwards step in policy and sector development.

The next major blow to ICTV was the re-allocation of Imparja’s second satellite channel 31 to the newly established National Indigenous Television (NITV) in 2007.

Following the Howard Government’s abolition of ATSIC in 2003-4, and the mainstreaming of all Indigenous funding programs led to the Indigenous Broadcasting Program being moved into Department of Communications, IT and the Arts (DCITA). While recommendations of increased funding and updated policy in the 1999 ‘Digital Dreaming’ report and 2000 Productivity Commission’s Broadcasting Review had been ignored, the Indigenous media sector continued to lobby for a national free-to-air National Indigenous Television Service, to sit alongside the ABC and SBS, as a reduced version of the NIBS proposal.

Delegates at Redfern Summit in Sydney, April 2004

In 2004, the Federal Government announced a ‘Review into the Feasibility of Establishing a National Indigenous Television Service’. Options for a national service were discussed at a special Summit held in Redfern in April 2004. Given the remote sector’s progress on establishing ICTV, a dual-service model was collectively supported – a community TV service primarily aimed at remote audiences (ICTV) and the high-quality service aimed at regional and urban audiences (NITV).

However, the Federal government insisted on a single organisational structure. in August 2005, following the report of the Indigenous Television Inquiry (DCITA 2005), Minister Coonan announced $48.5million over 4 years for the establishment of a National Indigenous Television service to “build on the Indigenous Community Television narrowcasting service transmitted by Imparja Television”. Rather than providing a dedicated free-to-air channel for NITV, the government made the highly divisive decision of re-allocating Imparja’s satellite channel 31 to NITV. On 13th July 2007, the popular ICTV service was switched off and replaced by NITV. (see also Rennie and Featherstone 2008, Featherstone 2015).

Despite calls by the remote sector for NITV to allocate programming time and budget for remote productions, NITV focused on mainstream-quality programming and did not commission any remote content in its initial years.

Djarindjin RIBS broadcaster Bernadette Angus re-launching ICTV on the Westlink satellite 16 November 2009 (Photo: ICTV)

Discussions were held on how to continue ICTV at the 2007 remote media festival at Warakurna community, hosted by Ngaanyatjarra Media. This led initially to regular distribution of DVDs and hard drives of ICTV content and later, in 2009, the development of the indigiTUBE online platform in 2009, jointly managed by IRCA and ICTV, to enable on-demand access to ICTV content as well as streaming of the eight RIMO radio services. The InigiTUBE portal grew to include hundreds of videos in multiple languages and a growing national audience, however poor internet access and high data costs limited its uptake in remote communities.

Alternative means of distributing ICTV were explored, with ICTV eventually re-launched in 2009 as a weekend service on the Westlink satellite. ICTV secured additional funding in October 2009 to employ a full-time editor, part-time trainee and part-time Manager, and broadcast playout system. While many communities had to manually switch the decoder to receive the weekend service, some RIMOs installed timed switchers to automatically switch from NITV to ICTV on weekends. Remote audiences loved having ICTV back again, although the goal of a full-time service continued.

Belle Davidson told me one day that her generation were stopped from speaking language at the Warburton mission and did not learn their cultural songs or dances. She had learnt from listening to the songs and watching the way the old people danced in the EVTV Inma videos recorded since the early 1980s. I suddenly realised how crucial the cultural recording work was in revitalising cultural activity and supplementing traditional modes of knowledge transfer through the generations.

Belle Davidson at her homeland Ilurrpa 2005

Belle had become a key cultural leader, regularly bringing the women together for Turlku performances, recording of the Tjukurrpa re-enactments and teaching the girls and young women. Before heading out bush to practice Turlku, Belle would arrange a private viewing of the videos stored in the Minymaku (Women Only) cupboard.

As Belle described:

This culture will not die out, it will always be here. We keep on making new videos of those Tjukurrpa stories with the people who are alive today. It is important that we keep looking at the old videos of the early day Inma so that we keep learning from them. Just to hear exactly how the songs were sung by the old people. That is why we are recording all of that. They learn from those old videos so that they can sing the songs confidently because they know the words. And that's very good. (pers. interview 2010)

Yarnangu were always generous in sharing their culture and promoting awareness

Ngaanyatjarra Minyma (women) dancing in the Turlku performance at the Perth International Arts Festival at Sunken Gardens UWA, March 2007.

The annual Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja caught the attention of the Perth International Arts Festival, who invited Ngaanyatjarra Media to present a multi-media Turlku performance at the 2007 Festival. During 2006, we worked with traditional owners to create videos of five key Tjukurrpa (songlines) from the region, arranged dance and arts workshops, and select singers and dancers. In February 2007, a convoy of vehicles with 33 Ngaanyatjarra elders travelled 1800km to Perth for the two nights of powerful cultural performance. The incredible trip included a Noongar cultural exchange, meeting West Coast Eagles football heroes, social activities and second-hand clothes shopping.

This led into an ongoing series of Turlku events across the region throughout 2007-9, including a cross-cultural visit by the Mornington Island Dancers.

Despite extensive advocacy over many years, and minor upgrades to microwave telephony and satellite internet in 2002-3, the Ngaanyatjarra region’s telecommunications was among the worst nationally.

Fibre optic cable being rolled out as part of Ngaanyatjarra Lands Telecommunications Project in 2007.

From 2004, the Shire of Ngaanyatjarraku, Ngaanyatjarra Council, Ngaanyatjarra Health and Ngaanyatjarra Media began working together with WA Government to develop a $6.5 million Ngaanyatjarra Lands Telecommunications Project (NLTP). I was appointed regional representative on the NLTP steering committee and got a fast-tracked education in broadband infrastructure and government processes. Telstra won the contract to roll out a fibre optic network connecting the six largest communities and upgrade community exchanges, completed in 2008.

A second stage was undertaken by Ngaanyatjarra Media, installing broadband satellite services in the remaining six communities along with free community access WiFi in all twelve sites. Ngaanyatjarra Media installed satellite dishes and WiFi, along with replacement broadcast towers in all communities. As well as enabling much improved services for health, education, and other agencies, Yarnangu could access the internet freely for the first time. The fibre connectivity also enabled mobile coverage to Warburton community in 2009, with mobile installed in the other five communities a few years later and rapid uptake of mobile devices. Ngaanyatjarra Media provided regional training in using online activities including internet banking, web searching, and connecting with family and friends via Facebook and email. (See article for more details.)

After 5 years of fundraising and planning, the Ngaanyatjarra Media and Communications Centre was finally constructed in Irrunytju, with an opening celebration in October 2008.

The new Ngaanyatjarra Media and Communications Centre.

Over $2.5m in funding was raised from 10 different agencies to achieve the project. The Centre included dedicated spaces for a community access telecentre, two radio studios, TV/music studio, archive facility, video edit rooms, meeting room, offices, server room and enclosed vehicle and equipment storage. We finally moved from the back room of the community office into our new building.

Wati (male) Chairperson Winston Mitchell (with nguti head-dress), Noeli Roberts and Belle Davidson cut the ribbon at the launch of the Centre in October 2008.

The media centre soon came alive with activity, with a range of activities underway at any time. It wasn’t unusual to have 10-20 people in the telecentre, 4-5 people in the radio studio, video productions underway, a band rehearsing in the studio, and several people in the office space. The Centre was the hub for our team, now grown to 6 non-Indigenous staff supporting over 25 Yarnangu across the region with regular trips for training, coverage of events, music workshops or technical maintenance.

In 2009, Ngaanyatjarra Media produced a long-awaited second part of the Minyma Kutjarra Tjukurrpa (Two Sisters Story).

Belle Karirrka Davidson and Winnie Woods acting as the two sisters in the 2009 production of Minyma Kutjara Tjukurrpa (Two Sisters Story)

Continuing from where the 1999 film left off, the film documented the next stage of the two sisters’ northward journey from Irrunytju to Tjanpitjarra near Docker River. Belle Davidson and Winnie Woods played the parts of the two sisters. As Belle Davidson described:

When I was the chairwoman, I went out and did the dancing and acting for the next part of the Two Sisters Story. At each place we stopped and acted out that part of the story. Because that is how you learn from seeing the story being acted out at those sites and that's what I was doing. Many of my family were involved as well.

The two-week production involved over 40 elders travelling in convoy to 16 sites, traversing 200km of tracks and searching through dense bushland. Noeli Roberts and Lance Eddy narrated the story, with old friend Neil Turner helping translate and support production.

With the media centre now completed, we were able to focus on the day-to-day work of Ngaanyatjarra Media.

Boys doing Kalaya Turlku (Emu Dance) at Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja (Ngaanyatjarra Music and Culture Festival), Irrunytju, August 2009 (Photo: Nina Tsernjavski)

I soon realised how the various activities - radio broadcasting, video production, IT programs, music development, cultural heritage and archiving, and technical services (described as case studies in my thesis) – all complemented one another in an integrated way to generate community engagement and meaningful outcomes. With central coordination and strong Yarnangu governance, we had finally developed a RIMO model that worked.

The next challenge was sustainability, how to keep these programs operating with inconsistent funding streams. While the 2000s marked a significant period of development of media and communications infrastructure and introduction of digital technology, it was now time to focus on consolidating these program streams and contiuing to build the capacity of the Yarnangu team.

The 2009 Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja, held in Irrunytju, was a highlight for me. Watching the young boys and girls proudly dancing demonstrated the importance of the cultural revitalisation work led by Noeli, Belle and other elders.

Alyuntjuru Band performing at Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja (Ngaanyatjarra Music and Culture Festival), Irrunytju, August 2009

Watching the confident performances of bands from across the region highlighted the music development program’s impact. Seeing the Yarnangu media crew filming the event and broadcasting it live over Ngaanyatjarra Radio made the years of training worthwhile. With a sense of accomplishment, I sat back and enjoyed the show.

After an incredible but exhausting 8 years, I felt the time was coming to move on. I worked with the Board and staff throughout 2009 to prepare for the transition. In early 2010, I undertook a handover to the newly recruited General Manager Patrick Donovan.

Belle Davidson, myself and Noeli Roberts at my farewell event, May 2010.

As I was preparing to leave in May 2010, the Board organised a farewell ceremony. Many of my Yarnangu friends travelled from across the Lands to perform a goodbye Turlku, including children of all ages. I was deeply honoured when Noeli Roberts presented me with the nguti (headdress) that he had worn in many Turlku ceremonies. As I stood with my dear friends Noeli and Belle, recalling our work together over the last nine years, we were suddenly surrounded by dozens of others who had been part of this life-changing journey.

The most important element for Ngaanyatjarra Media’s sustainability was continuity of Yarnangu leadership.

Wati Chairperson Winston Mitchell and Minyma Chairperson Winnie Woods, 2008

Minyma (female) Chairperson Winnie Woods described the importance of building opportunities for future generations:

The media has changed…it’s growing like fire, it’s gone big and we want to see it that way. And we’re all working together to keep this media going so our next generation will take it on when we disappear from the Lands, we want to see media grow and go forward on and on. (interview 2010)

Noeli Roberts and Belle Davidson had ensured that Ngaanyatjarra Media maintained its strong cultural focus, both leading cultural activity across the region well into their 70s.

Noeli Roberts with his grandson at the 2006 Ngaanyatjarraku Turlku Purtingkatja, Kanpa. (Photo: Valerie Bichard)

Noeli described his work over 25 years:

I worked around the Ngaanyatjarra area, organising Turlku events and filming of Tjukurrpa. And now Ngaanyatjarra Media is going good. And we still getting media to go every way, showing the way for people, putting all the pictures on ICTV, everything. Recording, telling stories, all the country on the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. And keeping it going from generation to generation. And we want the next generation to go up, for the media to keep going all the way. (pers. interview 2010)

Belle also reflected on her legacy:

For a long time I have been teaching women, and men and children the Tjukurrpa stories. Because that law and culture will never die, will always be there, for the children coming through, for the babies that haven't been born yet, and the generations to come. And I am thinking, when I pass away, who is going to do this work. (translation of interview with Belle Davidson 21/9/10)

After 9 incredible years at Ngaanyatjarra Media, I relocated to Alice Springs in May 2010 with my partner Bronwyn Taylor, where we bought a home and started a family. Our first child Anuwa (named after Noeli’s grandson) was born in March 2011 and our daughter Senna born in December 2012.

My aim was to complete a neglected PhD thesis about remote Indigenous media using Ngaanyatjarra Media case studies. I undertook some contract work, including a much-needed project to begin archiving Ngaanyatjarra Media’s collection, and part-time policy and project work with Indigenous Remote Communications Association (IRCA). I wrote IRCA’s submissions to several Government reviews, including the 2010 Indigenous Broadcasting and Media Sector Review (see below) and the 2011 Convergence Review and Regional Telecommunications Review. In 2011, I accepted an offer from IRCA’s General Manager Linda Hughes of a part-time Policy and Projects Officer role.

The 2010 Indigenous Broadcasting and Media Sector Review, or Stevens Review, was a much-needed review of policy and Indigenous Broadcasting Program (IBP) funding arrangements. IRCA’s submission, Joining the Dots: Dreaming a Digital Future for Remote Indigenous Media, called for updated policy to acknowledge convergence and diverse program delivery, outlining a vision of RIMOs and RIBS supporting cultural maintenance and community development outcomes using broadcasting, digital media, online technologies and archiving. Many of IRCA’s recommendations were reflected in the final Stevens Review report, however the sitting Labor Government only implemented two of the 39 recommendations - relocation of the Indigenous Broadcasting Program to Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy (DBCDE) and NITV’s restructure and relocation within SBS. There was still no increase to IBP funding and no policy update to support the industry's development in a convergent era.

The remote sector argued against a Stevens recommendation of a single peak body, claiming that dedicated representation was needed for RIMOs and RIBS, with their unique regional network delivery model, language and cultural context, technology, employment and training needs, and multi-media program delivery. While the Government continued to push for IRCA’s amalgamation with AICA, those around during the 1990s NIMAA era felt this ‘one-size-fits-all’ model would marginalise the remote sector.

In preparing IRCA’s submission, I interviewed remote sector representatives about the importance and future for remote Indigenous media.

IRCA Bord and staff, 2011. L-R: Linda Hughes (General Manager), Directors Henry Augustine, Nelson Conboy, Jenni Enosa, Annette Victor, Louise Cavanagh, Jedda Purantatameri, Sophie Woods (IRCA Admin), Walter Lui, Constance Saveka. (Photo: IRCA)

I was inspired by their responses:

“Indigenous media is about empowerment of Indigenous people at grass root level, improved health and lifestyle, employment opportunities for our people. Also empowering young people so they’re not turning towards negative stuff and Americanism, they can take a different approach towards cultural maintenance, keeping Indigenous languages and culture alive in this country. It’s about preserving our culture and identity, like women’s business and men’s business, supporting people to live where they belong.” (Jenni Enosa, Chairperson, Torres Strait Islander Media Association, IRCA Director)

“We need to look at utilising satellite delivery to have our voices heard. We need specialised equipment and skills and knowledge to be able to work in this new digital environment. We need access for the people in most need, in remote areas.” (Nelson Conboy, Chairperson IRCA)

“Law and culture is very strong, that’s why we have BRACS, for a strong voice for our people in remote communities. Also telling stories, histories, documentaries about our old people’ stories. It’s very important our stories be told and archived for the next generations to come.” (Annette Victor, Chairperson Indigenous Community Television)

“Remote media does not only cover radio. We’re tired of being restricted. This is 2010, we want mainstream broadband services. We’re not just competent with radio, we do multi-media, IT, book publishing, music recording, technical services and training, we are actors, sound recordists, camera operator, editors, liaison officers, the whole works, managers, directors, we’re multi-skilled. It’s time we are taken seriously and recognised as part of the mainstream media service.” (Henry Augustine, Pilbara and Kimberley Aboriginal Media)

Following Linda Hughes’ resignation in late 2011, the Board asked me to be interim IRCA General Manager in early 2012. I enjoyed working with the IRCA Board and coordinating sector projects, events and advocacy with the remote media organisations, so in June 2012, I successfully applied for the General Manager role.

By 2012, IRCA had over 150 individual members, mostly remote broadcasters and media workers from the 120 Remote Indigenous Broadcasting Services (formerly BRACS) communities supported by the 8 remote Indigenous media organisations across central and northern Australia. IRCA's office was located in a large shed in Alice Springs’ industrial area, which we shared with ICTV’s growing team led by Rita Cattoni. As well as the jointly managed indigiTUBE platform, we worked closely with ICTV on strategic planning, governance training and advocacy efforts.

With the growing use of social media and mobile phones in remote communities, and introduction of iPads and online content platforms, IRCA set out to support the remote sector’s online capability. In 2013, IRCA employed Digital Projects Coordinator Liam Campbell to work on indigiTUBE’s radio streaming and audio content, upgrade the IRCA website and Facebook page and support remote media organisations with online and digital media projects.

However, the bigger task of effectively representing and supporting the diverse needs across the remote media sector seemed overwhelming for a small under-resourced peak body. In order to support the sector’s development, we first needed to develop IRCA's strategic plan, increase funding and staff capacity, and build partnerships to amplify its messages. Having been part of Ngaanyatjarra Media’s growth over 9 years, I was now embarking on a similar journey, working with IRCA’s Board and membership to develop its capacity and impact nationally.

There was significant concern about the impending loss of local TV broadcasting with the upcoming Digital Television Switchover planned for 2013. While towns and cities would retain terrestrial broadcast with an expanded suite of 16 TV channels, the Australian government’s plan for remote and rural Australia was to replace local broadcasting with a satellite delivered direct-to-home service on every household.

At an IRCA ICTV Remote Digital Technical Forum in June 2010, remote sector representatives had argued the importance of local broadcasting for cultural maintenance and called for a dedicated channel for ICTV on the new VAST (Viewer Access Satellite Television) satellite platform. While several innovative technology and policy solutions were proposed, the Government proceeded with the direct-to-home model, spelling the end of BRACS TV and locally specific language and cultural content.

All radio and TV services moved to the new VAST satellite in 2013, requiring a rollout of satellite dishes to eligible households across remote and regional Australia. IRCA was contracted to coordinate a project to upgrade RIBS radio satellite receivers in over 150 communities prior to switchover. Susan Locke, who had recently retired as PAW Media’ General Manager, agreed to coordinate the project. This led to Susan’s recruitment as IRCA’s part-time Policy and Projects Officer, managing a range of complex projects with incredible efficiency, including the 2013 RIBS RIMO Audit, 2014 Remote Media Archiving Strategy, 2016 Remote Media Audience Survey and more.

A positive outcome of digital switchover was ICTV’s successful bid for a dedicated full-time channel on VAST, enabling access by over 300,000 remote households. A launch event at Yuendumu in April 2013 celebrated this long-awaited achievement. ICTV’s slogan ‘Showing Our Way’ became well known in remote communities, with over 90% of remote audiences describing ICTV as their favourite TV channel in a 2016 survey.

ICTV has become the preferred TV service for remote audiences (Photo: Anna Cadden/ ICTV)

With a new playout system installed at Imparja television, the challenge for ICTV was the need for fresh content. With RIMO’s video production capacity significantly impacted by the IBP changes in 2007 and lack of alternate funding streams, this became a key topic of discussion at successive remote media festivals and the focus of an IRCA Remote Screen Content Strategy.

Several RIMOs, including CAAMA, PAKAM, PAW Media and Ngaanyatjarra Media, were funded to produce content for NITV’s new ‘Remote, Rural and Emerging Initiative’, aimed at increasing remote content (a recommendation of the Stevens Review and a separate review of NITV), and a 2014 ‘Songlines on Screen’ initiative by Screen Australia with NITV.

While PAKAM remained the key content contributor, ICTV began diversifying its contributor base and topics, sourcing videos from ranger groups, art centres, schools, youth programs and other remote organisations. Content was collated under daily themes – Our Way, Our Culture, Our Tucker, Our Music, Our Sport, Spiritual Way and Young Way.

Under Rita Cattoni’s dynamic leadership and a proactive Board, ICTV gradually grew its staffing and programming, including commissioning a ‘Bedtime Stories’ series, producing its own programs and renovating the industrial shed (after IRCA moved premises in 2016) with a studio and production facilities. In 2016, ICTV set up a dedicated online platform ICTV Play to align with its programming style and remote content focus, with IRCA taking over indigiTUBE as an expanded national First Nations multi-media platform (see below).

A key role of IRCA was to provide opportunities for the hundreds of remote broadcasters and media workers around the country to connect with peers, develop new skills, showcase work and revitalise enthusiasm for their important work in their communities. The annual National Remote Indigenous Media Festival (NRIMF) was the most important and anticipated event of the year, like a huge family gathering. The hosting and location of the annual festival alternated among the 8 RIMOs and typically between RIBS communities located near the coast and in central Australia, with the catchphrase ‘from the desert to the sea’.

While working part-time with IRCA in 2011, I helped coordinate the 13th NRIMF in Umuwa in the APY Lands of South Australia in October 2011, co-hosted with PY Media. It was great to re-stage the festival in Umuwa, where I first attended 10 years earlier when IRCA and ICTV were being planned. We celebrated the history of remote media with a ceremony to commemorate the start of EVTV in 1983.

Delegates, community members, cultural dancers and Minister for Indigenous Affairs Nigel Scullion (bottom right) at the opening ceremony for the 17th National Remote Indigenous Media Festival held in Lajamanu community in October 2015 (Photo: Wayne Quilliam).

The 14th NRIMF in 2012 was held in Djarindjin community on the beautiful Dampier peninsula of Western Australia, co-hosted by PAKAM. This event set the structure for future festivals with four days of skills workshops culminating in a final day show and tell and awards ceremony, daily industry forums, nightly screenings under the stars, and a closing night cultural performance and concert featuring local bands. The 2013 NRIMF was held in historic Ntaria (Hermannsburg) community in central Australia in October with co-hosts CAAMA and ICTV, with 200 people attended a fantastic, albeit hot, week of networking, knowledge sharing and skills development.

The 2014 festival was held on the tip of the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland, Northern Peninsula Area, co-hosted by Queensland Aboriginal Remote Media (QRAM), with events spread across the 5 Northern Peninsula Area communities. The logistics of getting 150 remote delegates to the northern-most tip of mainland Australia was astronomical, but it was an incredible week, as shown in the Festival video and NITV news story. There is also a fantastic video from the 17th festival, held in Lajamanu community in NT in 2015, co-hosted by PAW Media, which incorporates the animation, photography and video work produced by participants in the skills workshops.

With the new National Broadband Network (NBN) being rolled out with a satellite solution planned for remote Australia, there were concerns that the lack of telephony and mobile coverage in remote communities would not be addressed by NBN and issues of latency, speed and cost of satellite broadband would make remote Australians second-grade digital citizens. The remote media sector needed broadband connectivity for radio networks, remote training and online content sharing.

In June 2011, IRCA coordinated a ‘Broadband for the Bush’ forum where RIMOs, ICTV and community organisations outlined their challenges and aspirations and heard from NBN Co, Telstra, CSIRO and government agencies. This began an ongoing conversation and advocacy role for IRCA.

Building on my telecommunications experience from Ngaanyatjarra Media, I began actively advocating for improved remote Indigenous communications access and digital inclusion at national forums, on consumer committees, through delegations to Canberra and in policy submissions.

Other central Australian organisations shared concerns about telecommunications needs and digital inclusion in remote Australia resulting in the establishment of Broadband for the Bush Alliance (B4BA). A second Broadband for the Bush forum, held in Alice Springs in 2012, was well attended by First Nations media and other Indigenous organisations along with numerous industry, government and academic experts. The discussion became technical and policy focused and IRCA’s members felt largely excluded from the conversation.

75 participants attended the Indigenous Focus Day held in Darwin at Charles Darwin University in July 2015.

At the next Broadband for the Bush forum in April 2014, IRCA organised a dedicated Indigenous Focus Day with support from Australian Communications Consumer Action Network (ACCAN). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders shared experiences and challenges, described local projects and participated in workshops to identify communications needs and brainstorm solutions and policy positions. The Indigenous Focus Day became a key feature of each annual B4B forum.

From 2015, the B4B Forum grew in scale and impact, being held in different locations to broaden awareness and include other states’ voices. With a growing membership, B4BA was incorporated. However, by 2019 B4BA’s leadership had dispersed and, with many key goals achieved, it was wound up.

In 2015 Telstra approached IRCA to establish an Indigenous Digital Mentors project in remote Northern Territory communities over three years, to complement its mobile co-investment program with NT Government. IRCA developed a three-year project, entitled inDigiMOB, to work with local media and community organisations to deliver IT training and support and employ digital mentors, building from an initial eight NT communities and town camps in 2017 up to 20 by 2019. Building on the project’s success, funding was extended with the new demand-driven training program now expanding to South Australia and Western Australia.

IRCA’s focus during 2013 and 2014 was on developing the remote media sector’s capacity and sustainability in an era of increasing convergence, digital disruption and political conservatism.

Myself and Assistant Manager Jennifer Nixon (centre back) with IRCA Board members (L-R: John ‘Tadam’ Lockyer, Sylvia Tabua, Karl Hampton, Gilmore Johnston, and Simon Japangardi Fisher) in the new IRCA office, 2016. (Photo: IRCA)

In an era of neoliberalism, it was no longer enough to deliver our programs and submit annual funding reports. We had to build our business acumnen and strategic communications capability, and learn the government’s new language - outcomes-focused, return on investment, corporate partnerships, impact measurement, social enterprise. At the same time, RIMO income from government radio campaigns and sponsorships was dropping as spending shifted to online and social media platforms. In order to survive, we needed to build cohesion and common messaging within the remote sector. We organised several industry forums and planning meetings to address the growing challenges and developed a new strategic plan and vision for IRCA “to be a powerful and connected voice for remote Indigenous Australia”. IRCA’s role became about telling the story about the value and impact of the remote media sector across remote Australia.

Over the next couple of years, we upgraded our branding, website and newsletter. With Anmatyerr/ Kaytetye/ Alyawarr woman Jennifer Nixon appointed as Assistant Manager in 2015, we worked together to increase IRCA’s Indigenous staffing and expand our services and industry development projects. We focused on building partnerships with other Indigenous organisations, not-for-profits, government agencies, research and corporate sector to expand our impact, knowledge and resources across the areas of digital media, telecommunications, archiving, technology and so on.

The election of the Abbott Coalition Government in September 2013 marked the beginning of a neo-conservative era where ongoing Government funding and policy support for Indigenous broadcasting was no longer assured. In 2014 over 150 Indigenous funding programs were amalgamated from multiple departments into five streams under a new Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) , housed within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. This was an effective reversal of the mainstreaming of Indigenous services by the Howard Government a decade earlier.

To receive funding, all Indigenous organisations had to demonstrate how their activities supported the Government's three key priorities – getting kids to school, increasing Indigenous employment and building community safety. It slowly emerged that under IAS there was a $500m cut to the Indigenous budget and many long-term community-controlled organisations de-funded and replaced by mainstream providers.

The Indigenous Broadcasting Program was included in this change, with the new Minister for Indigenous Affairs Nigel Scullion reportedly considered abolishing the program due to lack of demonstrable outcomes in these target areas. An IRCA Board delegation travelled to Canberra in April 2015 to argue the importance of the remote media sector and its critical role in supporting all IAS priorities by producing and broadcasting locally targeted information in language to communities.

From this advocacy, IRCA was funded to coordinate a radio campaign to promote remote school attendance, with each RIMO working with schoolteachers, students and community leaders to develop engaging radio messages, interviews, songs and video clips to address locally identified challenges. This successful model of involving the community in creating localised media campaigns built trust and engagement, compared with generic government campaigns written and produced by urban agencies with very limited impact.

Another policy element of the IAS introduced in 2016 required all funded organisations to have at least 90% Indigenous employment by 2018. While the remote media sector was already at 80%, and IRCA at 50% of its 8 staff, many small remote organisations did not want to replace non-Indigenous staff from management, training or technical roles. Also, with relatively low salary levels, the sector could not compete with the better paid jobs offered by ABC, SBS and the corporate sector now seeking to build their Indigenous workforce. IRCA developed a workforce development strategy to promote the skills, staffing capacity and succession needed within the changing sector.

In 2016, IRCA undertook an audience survey in 11 remote communities to gather data on audience engagement with First Nations radio, TV, news and online content. The results highlighted the importance of locally relevant radio across remote Australia, with local First Nations radio the preferred source of news and information above television, social media and other sources. This contrasted with national data which found that social media had become a primary source for First Nations people, leading to more government information spending on social media platforms than radio. 91% of respondents said they listened to remote First Nations radio stations at least once a month with 80% listening weekly, of which 81% preferred listening in shows in language. 91% were regular viewers of ICTV.

The key reasons given for listening to First Nations radio were positive Indigenous stories (77%), local news and information (67%), hearing local language (56%), feeling proud and supporting local employment. This evidence of the remote sector’s high level of audience engagement helped in getting some spending on government and health announcement spending re-directed from social media to RIMOs. However, the drop in sponsorship revenue continued across the national sector.

From my experience of Ngaanyatjarra Media's ageing media collection, I knew of the growing urgency to digitise and preserve the important social and cultural heritage collections of locally produced analog video, audio and photographs held by many remote media organisations before they deteriorated.

Neil Turner and archive worker in the PAKAM archive room (Photo: PAKAM)

These unique collections contained culturally sensitive content which elders wanted kept on country under community custodianship and cultural protocols, not sent to major institutions for archiving.

Building on an industry forum about archiving of community media collections at the 2013 festival in Ntaria, IRCA establishing a working group with RIMOs, elders and representative of national institutions to develop a Remote Media Archiving Strategy in 2014. Susan Locke led our ongoing efforts to develop archiving capacity within the sector with some support from Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA).

PAW Media Chairperson Valerie Martin with an Our Media slogan.

In 2018, IRCA (now FNMA) received two-year funding to trial an appropriate archiving platform for the sector. Susan managed the project, selecting the open source Mukurtu platform to trial with three media organisations on a dedicated First Nations Media Archiving hub. To address the need for digitisation equipment and skills, we gained funding to establish a digitisation facility in Alice Springs and provide training and support to First Nations organisations and archive workers.

Following Susan’s retirement in late 2019 and my handover of FNMA’s management, I coordinated the archiving projects part-time from my new home in Castlemaine Victoria in early 2020. As well as the Mukurtu trial and digitisation facility planning, this involved compiling the many training resources Susan had developed into an online Archiving Toolkit. When I left FNMA in April 2021, Liam Campbell was recruited to manage the archiving projects, including the establishment of the new digitisation facility in Alice Springs.

In 2015, the then Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Nigel Scullion, decided to de-fund the ailing Australian Indigenous Communications Association and invited IRCA to become the new national peak body. This would be the fourth iteration of a national peak in the last 30 years, following on from NAIBA, NIMAA and now AICA (2004-2015).

Despite concerns about the potential implications of this top-down decision and inheriting the national sector politics, the IRCA Board was concerned that if we rejected the offer, the Minister may also de-fund IRCA and leave the sector without any peak representation. We decided there was little choice but to accept. However, this required a significant change to our governance structure, membership model, objectives, programs, everything really. To do this, we would first need the support of IRCA’s membership.

Having repeatedly argued that a ‘one size fits all’ peak body model didn’t work for the remote sector, I was now tasked with implementing one. At least we had the opportunity to develop a new peak body from the remote sector outwards, rather than being centralised on the eastern seaboard with the remote sector relegated to the fringes.

We held a Special General Meeting for IRCA members at the 18th National Remote Indigenous Media Festival in the Top End community of Yirrkala. IRCA Chairperson John ‘Tadam’ Lockyer and I had the challenging task of explaining the changes needed to the membership and Board structure for IRCA to become the new national peak body. Members were asked to endorse a change from individual to organisational membership, enabling representation of all remote, regional and urban First Nations media organisations across the country. In effect, our current membership had to vote themselves out of having a vote. Graciously, they voted unanimously to accept the changes.

Our biggest challenge now lay ahead, to transform IRCA into a national peak body and re-build cohesion and shared direction within the deeply divided national First Nations media sector.

In May 2017 we organised a summit in Alice Springs (Mparntwe), entitled CONVERGE, to bring the national sector together. With diverse challenges and a lack of policy focus within the sector, we chose the slogan ‘meeting together - moving in one direction’.

Dot West facilitating a session at the CONVERGE Summit in Mparntwe (Alice Springs) 2017

There was a lot riding on this event, with IRCA having to prove that it could effectively transform to represent remote, regional and urban organisations as the new national peak body. This was made more challenging by Minister Scullion not issuing an official statement about his decision, with the inevitable hostility directed at IRCA. We had already renewed the constitution, developed a draft strategic plan, revised our policies and programs, and changed the staff structure.

The wonderful Dot West facilitated the CONVERGE Summit. A pioneer of First Nations media and Chair of NIMAA in the early 1990s, Dot had agreed to join the IRCA Board in 2016. Dot was to become the first Chairperson under the new governance model, with her strong leadership instrumental in navigating the transition period and re-uniting the divided sector.

At the opening plenary, Dot described the work put in during the 1980s and 1990s to establish Indigenous broadcasting sector:

“It took collaboration, working together and supporting each other across this country to achieve what we have today. Certainly, what we have is far from the vision our early pioneers had set us, but we have achieved milestones against the odds. I attended Indigenous media conferences as far back as the late 1980’s where we talked about having an Indigenous Broadcasting Authority, like the ABC and SBS, we talked about employment, where people were paid a decent salary, technical training and support, ensuring there were Indigenous media services blanketing the whole of the country, not just pockets of the country.” (Dot West 2017)

Having revisited the past key policy moments, Dot outlined the unmet demands for updated policy, increased funding, capital and technology upgrades, increased employment, and autonomy of Indigenous media services to meet community needs, not just deliver government messaging. She concluded:

“How do we move forward and ensure our sector not only stays alive, but thrives into the future. What can we achieve so that our children, grandchildren and great grandchildren have a legacy they can be proud of, but more importantly is relevant and usable to them. Let’s put aside our individual castles and work together as one, while acknowledging and respecting our diversities and the common ground that brings us all together”.

Over the next two days delegates worked together at the CONVERGE Summit to define the key needs and policy actions needed in the sector. One workshop session was to develop value statements about why ‘Our Media’ is important to our communities, with 12 key statements collectively developed and selected. Delegates were photographed holding their favourite slogan:

CONVERGE delegates with the final 12 Our Media slogans, 2017

IRCA Assistant Manager Jennifer Nixon with TSIMA Senior Broadcaster and IRCA Director Sylvia Tabua and myself at CONVERGE Summit 2017.

Other statements identified First Nations media’ important role in saving lives, developing leaders, providing relevant news and content, creating partnerships, and promoting digital inclusion. The sector’s value was summed up well by IRCA Secretary Sylvia Tabua:

“Our media is very important to our communities – it keeps our languages and culture strong, connects our communities and families and provides meaningful jobs and skills. Our media creates and shares the stories, news and music we want to hear and provides a training ground for our young leaders.” (Sylvia Tabua 2017)

A Communique from CONVERGE 2017 outlined the key messages from the Summit, which marked a successful beginning in IRCA’s transition to become national peak body. The ‘Our Media’ statements became the seed for an ongoing sector-wide campaign.

We decided to build upon what had worked as remote peak body - a major annual event, clear policy focus, industry development projects and resources, and being responsive to members’ needs.

Building on this initial summit, the CONVERGE First Nations Media National Conference became the annual industry event. The next CONVERGE was held in Brisbane in March 2018 where the new name First Nations Media Australia (FNMA) was decided by the membership. Another CONVERGE was held in Sydney in November 2018, co-hosted by Koori Radio, where the inaugural First Nations Media Awards ceremony was launched.

A key outcome from CONVERGE Brisbane was the development of the 9 Calls for Action, the key target areas requiring updated government policy and funding support.

FNMA delegation to Parliament House in Canberra, August 2018: Karl Hampton (CAAMA), myself, Kaava Watson (BIMA), Dot West (Goolarri FNMA Chair), Vince Coulthard (Umeewarra media), Claire Stuchbery (FNMA), Jodie Bell (Goolarri Media) and Jenni Enosa (TSIMA)

Several of these echoed calls made since the 1990s, including the need for increased operational and employment funding, training and career pathways, facility upgrades and a dedicated Indigenous broadcasting licence category. Others were new and emerging needs, including news and current affairs, archiving, being a preferred channel for government messaging, and digital and online technology to enable multi-platform delivery.

In August 2018 a delegation of FNMA Board members and sector representatives launched the Our Media Matters campaign in Canberra and held over 40 meetings with politicians and government agencies to promote the 9 Calls for Action in the leadup to the Federal election.

The Our Media Matter campaign and 9 Calls for Actions helped provide a unified sector voice and targeted policy focus, fostering Government engagement with the sector’s development. Consequently, FNMA’s membership steadily grew and the mistrust and rivalries gave way to a more cohesive and forward looking sector.

While CONVERGE became the new national event, we committed to continuing the Remote Indigenous Media Festival (RIMF) as a biennial industry event for the remote sector

Tjawina Roberts, Roma Butler and Noeli Roberts showing delegates a Minyma Kutjarra Tjukurrpa (Two Sisters Story) site near Irrunytju during the 19th Remote Indigenous Media Festival, September 2017 (Photo: Jeff Tan)

The last of the annual festivals (RIMF 19) was held in Irrunytju community in September 2017, co-hosted with Ngaanyatjarra Media. It was a bitter-sweet event for me returning to my former home community, with my old friend Belle Karirrka Davidson having passed away a few months earlier, and Noeli Roberts no longer able to walk. Ngaanyatjarra Media had been through difficult times in recent years but was back in full swing. Despite the wild desert weather of heat, wind and rain, it was a very memorable event with incredible skills workshops, vibrant discussions, cultural tours and dancing, history and celebration.

TSIMA Senior broadcasters Jenni Enosa (Preston Award winner) and Sylvia Tabua (Mr Garawirrtja Award winner) with myself and TSIMA Operations Manager Diat Alferink at the closing night event for the 2019 Remote Indigenous Media Festival.

When ICTV established its new ICTV Play platform in 2016, IRCA took over full management of the indigiTUBE platform. In order to represent its new national membership, IRCA sought funding to re-develop and expand the platform to stream 27 First Nations radio stations and showcase the sector’s diverse cultural expression and content types - music, video, podcasts, language recording, oral histories, news, archives and more.

indigiTUBE is an online showcase of First Nations radio, video, music, languages and culture

The re-development was led by Project Manager Jaja Dare (Wiradjuri) and the new indigiTUBE platform was officially launched at the inaugaral First Nations Media Awards ceremony in Sydney in November 2018. An indigiTUBE app was also developed to enable access on mobile devices.

Content could now be viewed by contributor, media type or genre, with a map interface and curated channels for current topics such as NAIDOC Week, Black Lives Matter, COVID-19 messages and more. The audience and engagement grew in Australia and internationally, including schools and universities using the platform to promote awareness of First Nations language, culture and storytelling.

indigiTUBE also provides a content sharing portal, enabling First Nations broadcasters and producers able to download approved content, such as radio documentaries, news, podcasts and music, for re-broadcast. This functionality led to FNMA embarking on the ‘First Sounds’ project in 2019 to promote and nationally distribute quarterly selections of new First Nations music, in collaboration with Community Broadcasting Association of Australia’s AMRAP project. First Sounds’ popularity has helped build the profile and audience for emerging bands and musicians across the country.

A study of the Social Return on Investment of First Nations broadcasting services, commissioned by Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2017, found that for every dollar invested in the sector $2.87 of cultural, social and economic value was returned.

Over 150 delegates gathered in Mparntwe for the 2019 CONVERGE First Nations Media National Conference, November 2019. (Photo: Oliver Eclipse)

It found that First Nations broadcasters and media producers provided a local and trusted voice and delivered employment outcomes, strengthened social cohesion, language maintenance and cultural resilience. A key finding was that “Indigenous Broadcasting Services provide much more than radio – they are community assets that contribute to strengthening culture, community development and the local economy” (Social Ventures Australia, 2017).

The First Nations media sector today employs over 500 people nationally, more than 79 per cent of whom are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (FNMA 2020). It includes over 35 licensed First Nations media organisations reaching 230 radio broadcast sites, which collectively reach 48 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population of over 650,000 people (FNMA 2020). It also includes NITV, ICTV, National Indigenous Radio Service, Koori Mail, and numerous other First Nations online news and social media platforms. While the sector has matured significantly since the 1990s, it continues to advocate for its 9 Calls for Action to help realise its potential.

Building on a recommendation from the 2017 Indigenous Focus Day that digital inclusion and communications access become a ‘Closing the Gap’ target, IRCA advocated for this outcome over several years. In 2019 the Federal Government announced a 10-year review of the failed Closing the Gap framework. First Nations Media Australia joined a coalition of 40 national peak Indigenous organisations which successfully called for a National Partnership Agreement with the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG) to co-design and co-deliver the revised framework and targets. After two years of intense negotiations, the new Closing the Gap framework was finalised in 2020, which included Outcome 17 – ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have access to information and services enabling participation in informed decision-making regarding their own lives’ - which encompassed measures for First Nations media participation and audience reach and an ambitious target of digital equity by 2026.

However, the challenge was a lack of data to measure the digital gap in remote indigenous communities, likely the most digitally excluded group in Australia. The only national audit of digital inclusion, the Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII), did not survey remote communities, and the internet access question was removed from the national Census after 2016. Based on data from regional and urban Australia, the ADII had found that the digital gap for First Nations people had widened since 2018, with one-off surveys showing a significantly greater gap in remote communities. In order to measure the digital gap in remote Australia and advocate for targeted policy and programs to address it, dedicated research was needed.

I continued to pursue this issue beyond my role at FNMA, undertaking a Remote Indigenous Communications Review report for ACCAN in 2020. In 2021, I was invited by the ADII team at RMIT to lead a new research project entitled ‘Mapping the Digital Gap’, a four year longitudinal study of digital inclusion and media use in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Since becoming national peak body, I knew that FNMA needed to have a First Nations person as CEO.

FNMA team at First Nations Media Awards, Alice Springs November 2019 – Mikayla Friday-Shaw, Jacinta Barbour, Claire Stuchbery, myself, Jennifer Nixon, new CEO Catherine Liddle, Stephanie Stone, Myers Sandy, Barbara Clifford, Susan Locke (missing from photo: Ben Pridmore, Jaja Dare and inDigiMOB team Ben Smede, Steve Tranter and Metta Young) (Photo: Jeff Tan)

Having completed the consolidation of FNMA and implemented the initial strategic plan, the time was right. The Board began an exhaustive recruitment process in late 2018, with Arrernte woman Catherine Liddle appointed in October 2019. We undertook a three-month handover process, through to early 2020.

At the CONVERGE national conference in Alice Springs in November 2019, we proudly introduced Catherine as new CEO. I was pleased to be able to step back and watch FNMA under strong leadership, along with Chairperson Dot West and a fantastic Board. Dot surprised me at the First Nations Media Awards ceremony by presenting a special award for Recognition of Contribution to the First Nations media industry. It was humbling to be recognised among the many people who had played a role in the industry’s development over its forty year history.