Nobles & Savages on the Television

Twenty Years On, by Frances Peters-Little

As a part of the celebration of Satellite Dreaming Revisited, I have offered to also revisit an essay I wrote twenty years ago called ‘Nobles and Savages on the Television’. The essay had been a part of my MPhil thesis called The Return Of The Noble Savage By Popular Demand : A Study Of Aboriginal Television Documentary In Australia, which I submitted in 2002. I wrote the essay as a result of having worked in television at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s. It had been a period of transformation and optimism for both the ABC and young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers, like me, working in mainstream television. The concept of the noble savage was not an unusual topic of discussion among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the arts, and film and television industries in those days, so my essay was not a new idea when I wrote about it. I intended to raise what I felt was the repetitive use of noble savage imagery in film and television, and the way in which scholars wrote about us.

Frances Peters-Little in 'Satellite Dreaming', 1991

At the time that I was interviewed for Satellite Dreaming, I was directing my first film (Oceans Apart), a film about urban Aboriginal people who lived very non-traditional lives but who strongly identified as Aboriginal nonetheless. In the film I was presented as an Aboriginal filmmaker who appeared as if she was an inexperienced filmmaker at the ABC, under the tight control of White executives. This was not entirely true because I had already worked on several films previously and had a degree in Communications after working for several years at a Sydney community radio station. At the time I was being interviewed, I understood that Satellite Dreaming was a film looking at the emerging Aboriginal film and television industry in central Australia, and how television might destabilise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s culture. Upon reflection, I realise I had always felt that my film Oceans Apart, like Satellite Dreaming, shared the view on identity politics that proved how, irrespective of whatever interventions might be made upon our lives, we would not only survive but indeed thrive under such conditions.

Satellite Dreaming went to air on the ABC in 1991, the same year as Oceans Apart, with the backing of our Aboriginal Programs Unit (APU) where I worked with a team of Aboriginal producer/directors and researchers.

Some of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Satellite Dreaming made the comment that we needed an Indigenous controlled television broadcaster that aired nationally to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander audiences and mainstream Australia. Now that this has come about with the establishment of the National Indigenous Television (NITV), broadcasting through the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), the question is: have all our problems been resolved, or are we left with a new set of problems to overcome?

In this preface I will very briefly sum up what has occurred since I wrote my essay in 2002, try to answer the above-mentioned questions, and revisit the concept of the noble and the savage in our image-making and production values. Before I continue, I need to mention that these days I no longer make films, nor do I live in Sydney or Canberra or write academic essays. Instead, I live on my mother’s traditional lands – Yuwaalaraay country – as an elder of my community, which gives me great peace and satisfaction. I also spend my time doing other things like painting and writing my family’s history, and working to supporting young Yuwaalaraay artists and singers through my father’s foundation, the Jimmy Little Foundation.

Perhaps the most obvious changes in the contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander film and television industry are the numbers of productions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander films made, the production levels, their exposure to broad audiences around the world and the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers. Since my days of working in television, the institutions that have been most impactful are the First Nations Department at Screen Australia, the ABC TV Indigenous Department, NITV and SBS, Imparja TV and community broadcasting; that is, the Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme (BRACS) and the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), as well as the endorsement of protocols and guidelines for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander production. I will not be referring to Imparja TV, BRACS and CAAMA, as they have already been written about by so many. What I will be referring to is mainstream Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander film and television films and programs.

When I began at ABC TV, they had already established an Aboriginal Programs Unit (APU) in 1987 and this later became the Indigenous Programs Unit (IPU). In those early days, we produced series such as The First Australians (1988), Blackout (1989), Kam Yan (1995), Songlines (1995) and Messagestick (1999), which were documentaries and magazine programs. By 2010 the IPU’s objective was to develop quality primetime Indigenous drama; hence, we began producing several dramas such as Redfern Now (2012), Gods of Wheat Street (2013), Black Comedy (2014), 8MMM (2015) and an international genre series Cleverman (2016). SBS TVs principal purpose was to provide multilingual and multicultural broadcasting to inform, educate and reflect Australia’s multicultural society. As a result, SBS produced an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander series called First In Line (1989). Key persons involved were producers Cyndia Roberts, Lester Bostock, and presenters Rhoda Roberts and Michael Johnson.

While he was there, Bostock wrote a booklet called The Greater Perspective, referred to later in this essay. By 2012, NITV was a fully developed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander television broadcaster operating out of SBS TV as a national free-to-air channel on Freeview, on channel 34. To this day NITV continues to broadcast 24 hours a day, seven days a week, airing news and current affairs programmes, sports coverage, entertainment programs for children and adults, and films and documentaries covering a range of topics presented and produced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Screen Australia, however, is not a television broadcaster but a government body. Formally known as the Australian Film Commission (AFC) and founded in 1975, its function is to fund and assist with the production of Australian films. By 1993, it had established an Indigenous unit whose purpose was to promote quality films with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content. Since then it has been responsible for the production of at least 150 films for television or cinematic release, with feature films like Bran Nue Day (2010), Jasper Jones (2017), Radiance (1998), The Sapphires (2012) and One Night The Moon (2001). These films have won numerous prestigious awards at Cannes, the Berlin, Toronto and Sundance Film Festivals, and the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA).

In many ways the establishment of such government bodies and policies (and I am deliberately not mentioning commercial television channels like 7, 9 and 10 or production houses like Film Australia, the Australian Film, Television and Radio School and other educational institutions) added to the rapid increase of films produced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers. For the most part they were collaborative works produced by White and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers, and while the number of films produced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers was on the rise, the number of films about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander topics made by non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers was on the decline. This is largely because of policies adopted by Screen Australia and the television broadcasters like ABC, NITV and SBS that are premised on the protocols and guidelines originally introduced by Bostock’s The Greater Perspective. In recent years we can add the Pathways & Protocols : A Filmmaker's Guide To Working With Indigenous People, Culture and Concepts drawn up by the Terri Janke and Company lawyers, as well as consultants who set a preference for any non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmaker making a film about an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subject being advised to bring an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person on board.

While on the surface it looked as though this was a good thing, I remember feeling sceptical at the time about the possible threats of the over-policing of Indigenous storytelling, which I thought might eventually backfire on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers. I also thought that while the onus was on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be involved, many non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people might shy away from making films about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In my view, that is not such a good idea, considering that the filmmakers I was inspired by were indeed non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers, such as Alec Morgan, Carolyn Strachan, Alessandro Cavadini and many others.

I think back on my final days of working in television when the view that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were the only ones who knew how to best understand and make films about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subjects became progressively more popular. I remember working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers who were not at all interested in politics and did not grow up in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, but who pressured some of us to only say ‘positive’ things about our communities, leaving little room for critical analysis. I was told by my then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander producer to remove all ‘negative’ images of alcohol in the shots, and try to start reaching out more to White audiences in the hopes of gaining their acceptance of us as ‘equal human beings’. Needless to say, I railed against such suggestions and subsequently resigned because of that request. Some years later I was inspired to write an article on this topic for an Australian arts magazine called Arts Monthly; my article was titled The Impossibility Of Pleasing Everybody: A Legitimate Role For White Filmmakers Making Black Films[1] which of course got me into all sorts of trouble.

When I left television, I noticed there had been a shift of interest about those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander television makers in mainstream television towards feature filmmaking and drama. It was a time when scholars and filmmakers became enthralled with programs made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers operating out of central Australia and Australia’s first national satellite system, AUSSAT. There was also an upsurge of scholars writing about filmmaking in central Australia. It had been what author Melinda Hinkson described as a whole new industry of writing about Aboriginal broadcasting in remote Australia, inspired by anthropologist Eric Michaels.[2] However, there were at least two US scholars who took an interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander documentary filmmaking in mainstream television: anthropologist Faye Ginsburg and Megan McCullough. Ginsburg saw the significance of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander television documentary-making in mainstream television [3] and Megan McCullough argued that author Marcia Langton [4] may have been too quick to write off those urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers producing documentaries for mainstream television [5]. But those days seem so long ago and we have, I think, had an about-face and returned to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander program makers and filmmakers working in mainstream television at NITV.

There are so many good things about NITV that excite me. They screen not just television programs about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but sports of all kinds, Indigenous music programs, and shows about other Indigenous nations around the world. They are doing a spectacular job of putting together content to go to air 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and presenting daily news updates that leave the rest of the news and current affairs about Indigenous people behind in the dust. It is, I suppose as close to the dream I had back in those days when I came to television and even after my essay about nobles and savages. But if I have any criticism about the state of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander film and television today, it is that it needs to be a bit bolder – taking the risks and daring to become critical of our communities and individuals, finally releasing ourselves from the noble and savage binary, and saying what needs to be said to give a voice to those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are often overlooked.

So I leave you with my essay about nobles and savages, which incidentally still exists in many ways, and perhaps is reproduced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers in some regards, because the narrative is one that was entrenched in so many of us a long time ago, but I’ll leave that up to you to decide.

The sweet voice of nature is no longer an infallible guide for us, nor is the independence we have received from her a desirable state. Peace and innocence escaped us forever, even before we tasted their delights. Beyond the range of thought and feeling of the brutish men of the earliest times, and no longer within the grasp of the ‘enlightened’ men of later periods, the happy life of the Golden Age could never really have existed for the human race. When men could have enjoyed it, they were unaware of it and when they have understood it, they had already lost it. J.J. Rousseau 1762 [6]

Although Rousseau lamented the loss of peace and innocence; little did he realise his desire for the noble savage would endure beyond his time and into the next millennium. However, all is not lost for the modern man who shares his desires, for a new noble and savage Aborigine still resonates across the electronic waves on millions of television sets throughout the globe.[7]

Despite the numbers of Aboriginal people working in the Australian film and television industries in recent years, from the 1950s to the turn of the twentieth century, cinema and television continued to portray and communicate images that reflect Rousseau’s desires for the noble savage. Such desires persist not only in images screened in the cinema and on television, but also in the way they are discussed. The task of relieving such desires for the noble and the savage in non-fiction film and television making is a difficult one that must be consciously dealt with by both non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal film and television makers and critics. With underlying desires for the noble and the savage seeping into the colonial sub-conscious for centuries it is improbable such notions are likely to disappear after only three decades of Aboriginal policies in broadcasting.

I intend to demonstrate several examples where film and television makers continue to use images and concepts reflective of Rousseau’s noble savage to describe Aboriginal people’s co-existence and/or resistance to colonisation. This is not to necessarily attack the works of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal filmmakers; rather, it raises questions about why they consistently position Aborigines into noble and savage stereotypes. While it is generally thought film and television makers deliberately create racist stereotypes [8], I say it is more complex than that, for I am yet to meet anyone who makes a film for the sole purpose of inciting racial hatred. This is a point well noted by Aboriginal scholar Marcia Langton who says racial discrimination, while a problem, is not necessarily intentional but a particular factor underlining specific and/or general encounters between Aborigines and filmmakers [9]. While I intend to explore noble and savage stereotypes, I intend to argue that in recent years the noble pole has intensified to counteract past representations of Aborigines as savages and that the noble pole is just as damaging as the savage pole, simply because Aboriginal people are neither noble nor savage.

While it is suggested by scholars and critics that Aboriginal production techniques, aesthetics and politics serve as an alternative to the way non-Aborigines make programs [10]. I am not entirely convinced of this argument. Alternatively, I believe Aboriginal film and television makers have more in common with non-Aboriginal film and television makers than we may think. After three decades of well-intended self-determination policies, and Aboriginal people emphasising that we live with the problem and therefore we are the only people who are capable of fixing the problems [11], I think it is time to allow ourselves to challenge the rhetoric of the 1970s [12]. Various Aboriginal film and television makers who say that only Aboriginal people are capable of telling authentic Aboriginal stories [13] conflict with the theory that realism is subjected to the creator and the personal choices they make [14]. I further say that as much as film and television making is a personal choice, there is however an attainable middle ground that can be reached between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal filmmakers: to choose to make films and television programs in such a way that we can intersect the constant pendulum swing between the noble and savage poles. In my attempt to highlight the binary framework of nobles and savages, underpinned by longstanding colonial leanings, I will demonstrate where I think noble and savage imagery has endured. I also argue that fiction has become the more noble format of storytelling in Aboriginal film and television making, replacing non-fiction program making at the savage end of the pole. I raise the question of why vast number of scholars prefer to pay extra attention to film and television making in remote Australia (the highbrow culturally noble) than those who write about Aboriginal filmmakers working in mainstream television in urban Australia (the low-brow, politically savage). I also suggest that in recent years Aboriginal filmmakers who make fiction films (drama) in film and television are celebrated more than those who work in non-fiction programs.

As an Aboriginal documentary filmmaker I do not claim to know what the perfect Aboriginal film is, and I would challenge anyone who thought they did. I am nevertheless critical of filmmakers who continue to rework noble and savage images and concepts in their films and suggest that it is about time we had this discussion. I base my argument on the premise that Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal television makers, like everyone else, exist within a postcolonial society that rewards those who replicate noble and savage imagery [15]. I also admit that I too have made the mistake of presenting Aboriginal people as utterly righteous subjects/talent. Although I may have started out that way in the 1980s, I no longer feel it is necessary to continue working within that framework. In this paper I draw from my personal experiences as an Aboriginal filmmaker who grew up in a multicultural inner-city community, who joined the marches and demonstrations for Land Rights and Self-determination, who participated in the Rock Against Racism concerts and the anti-deaths in police custody movement, who made the transition from community radio into mainstream television, and who has grappled between the noble and savage poles, with all the muddy parts that exist between the two, in search of a better way to tell stories about our people.

Just to define a few key words, I refer to ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘non-Aboriginal’ as those who are of Aboriginal descent and those who are not, in preference to using the term Indigenous. Although many choose not to use the word Aborigines in preference to the word Aboriginal because they find the former offensive, I say the only difference is that Aborigines is a noun and Aboriginal is an adjective. Occasionally I will refer to Aborigines as Black-skinned, brown-skinned and fair; and non-Aborigines as Whites, especially where there are references to skin-colour. This is because the topic of skin-colour is relevant in visual mediums such as film and television. The term ‘mainstream broadcasting’ includes public television broadcasting such as the ABC and SBS as well as the commercial networks. ‘Network’ generally refers to the privately owned and controlled commercial channels. An Aboriginal documentary is a film that could be made by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal filmmakers as long as the content and subject is Aboriginal. The term ‘non-fiction format’ can be films, magazines, documentaries, and news and current affair items. The term ‘fiction’ includes drama, performance and some traditional storytelling, and can be both on television and in the cinema. Although there are examples where some filmmakers make the distinction between the independent documentary and the television documentary, independent documentaries are just documentaries made by filmmakers not employed by the broadcaster. Since it is rare to see non-fiction programs anywhere other than on television, I may sometimes refer to these films as television programs. Nor will I be making a distinction between digital tape, 16mm or 35mm etc., film or SP betacam, and/or various video or other digital formats.

I focus on the significance of the term known as the noble savage to highlight the paradoxical meaning that oscillates between the noble pole and the savage pole. I am suggesting that it is an ambiguous and variable term used to define perceptions of the other, and therefore will not be referring to its scientific meaning. I argue it is precisely because of its fluidity and ambiguity that the notion of the noble and savage has been able to endure for several centuries, existing before Europeans set foot on Australian soils. I examine these terms in parts because I want readers to understand why Europeans were able to revere and preserve the noble while hoping to destroy the savage. I am also fascinated with the irrational European concepts that aim to reduce the world’s population to such simplistic binary terms of good and evil, north and south, Black and White, real and unreal, etc. and continue to do so. To do this I have divided the following characteristic of 18th and 19th century imagery of the noble and savage and how it was used to classify Australian Aborigines into the following themes: (1) patrons of nature’s gifts (2) infantile creatures of innocence (3) Black naked brutes (4) torn between two cultures and (5) doomed for extinction.

Although it is thought Jean Jacques Rousseau coined the term, in the 18th century philosopher Maurice Cranston argued that authors and explorers referred to the noble savage (or the characteristics of the noble savage) as early as the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Proponents of the idea in one form or another included Christopher Columbus, Michel de Montaigne, Desiderius Erasmus, and Sir Walter Raleigh, who was particularly fascinated by the way savages obtained their food [16]. Seventeenth-century poet John Dryden referred to the noble savage when he wrote, ‘I am as free as nature first made man, Ere the base laws of servitude began, when wild in woods the noble savage ran.’[17] By the 18th century the French meaning of the word sauvage conveyed an uncorrupted innocence. Rousseau’s statement demonstrates that the noble savage was a concept by which Europeans romantically viewed other cultures in ideal terms and coveted them. Cranston says the concept of noble savage gained popularity at a time when Europeans felt they had lost the ability to make use of nature’s gifts, and were instead trapped in the tangled world of letters, magistrates, politics and commerce [18].

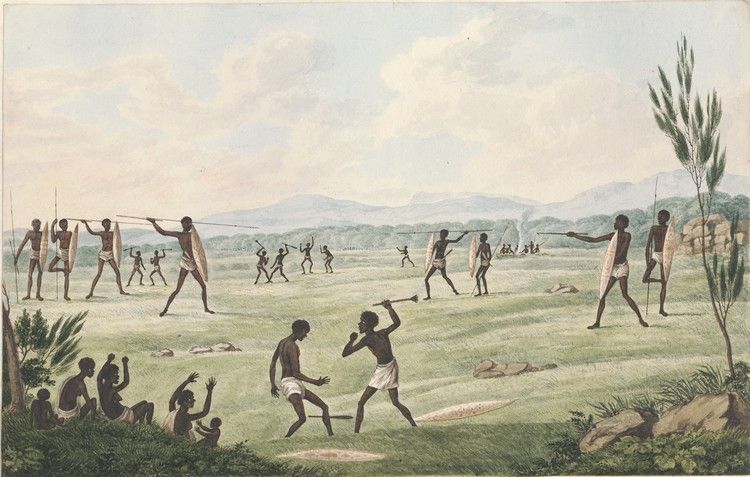

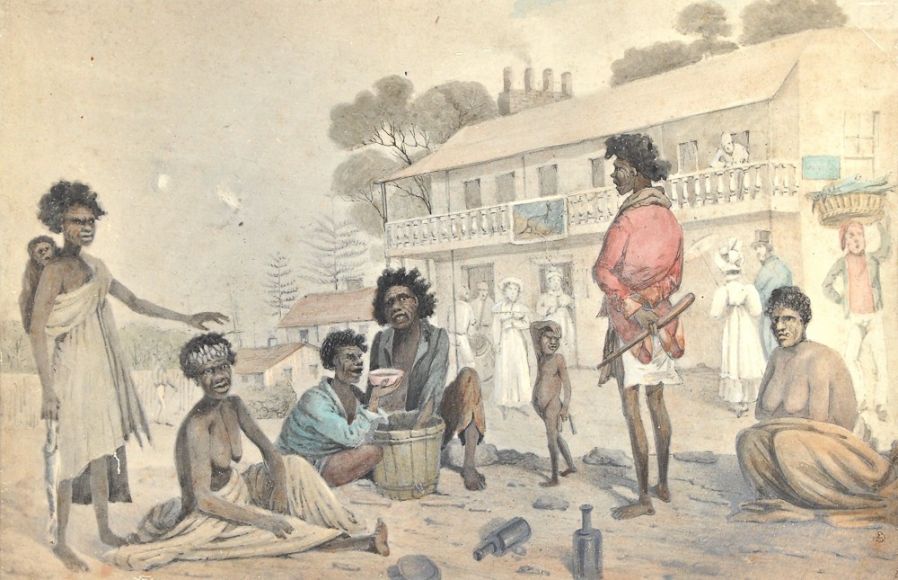

Joseph Lycett, A Contest with Spears, Shields and Clubs, c 1817

Interestingly 18th and 19th century scientists and artists, who ventured into new worlds searching for solutions to their own society’s over-commercialisation and corruption, are not that dissimilar to some contemporary documentary filmmakers who make films about other cultures. Although motivated by other reasons, their impulse to find solutions for their own societal problems by exploring other people’s culture has been a recurrent theme. Documentary filmmaker Gary Kildea is very sympathetic towards Aboriginal filmmakers who witness the way we see White filmmakers cruising through our communities. Kildea says that he/they are afforded the luxury of sailing through exoticism in their making films about Aborigines because they do not have to carry the political and social burden of responsibility that Aboriginal film and television makers do [19]. In my interview with filmmaker Alec Morgan, I asked why White filmmakers would even want to make films about Aborigines. His reply was that he wanted to make Lousy Little Sixpence because he needed to make sense of a White superficial world that greatly valued materialism, Gallipoli and jingoisms, but when it came to Aborigines they were yet to be treated as human beings deserving of justice and recognition [20]. Is it possible that Aboriginal filmmakers, who wish to escape the jingoisms and the superficial world of Whiteness are also attracted to filmmaking for the same reasons? Can we also be drawn in by the same cultural iconographies and symbolisms when filming Aboriginal communities that are other than our own, especially when we know at the back of our minds that we are aiming to reach White audiences [21]? And should that really matter?

Just as 18th century Europeans dreamed of a greater southern hemisphere, where an inversion of the Eurasian landmass might balance and contrast the corruptible and tangled world of the north [22], could we too be drawn to a promised utopia in central or north Australia? When Europeans first encountered Aboriginal people on the Australian continent, they viewed us through a double vision [23], from a false sense of superiority and objectivity. They saw Aboriginal people and the land in the same way they saw the two hemispheres; that is, through a framework supporting a simplistic dichotomy of opposing poles. The world for them at that time required that one be either civilised or uncivilised. No matter how enlightened they thought they were themselves, they were incapable of shaking off their double lens on the world, upholding their superior attitudes over those they sketched, wrote about, and recorded. By hypocritically praising those they had met, they perhaps thought they were acting in a most noble manner themselves. Without the excuses of their 18th century ancestors, there are many who still resort to binary terms when discussing Aboriginal people; for example, traditional or modern, and those who are traditional seem to be more interesting than those who are modern. Author Toby Miller draws an analogy when he writes that the rest of the world ceases to find Australia interesting when Australia becomes modern [24]. The suggestion that Aborigines in northern and central Australia have culture but urbanised Aborigines do not is a view that American scholar Eric Michaels mistakenly makes and he has possibly made that view popular. Author and anthropologist Melinda Hinkson suggests that Michaels spearheaded a small industry of scholars to write about Aboriginal television making in remote Australia [25], making it more popular than urban film and television making.

Shifting the argument in the opposite direction was Megan McCullough, an anthropology student at New York University, who wrote in her 1995 master’s thesis:

It is possible to see how Marcia Langton’s dismissal of mainstream television in Australia was perhaps hasty. The Aboriginal programs unit at the ABC demonstrates that Aboriginal mainstream television can effectively and interestingly juggle identity politics with the nuts and bolts of production, reception and distribution without compromising the complexity of the Aboriginal political positions and cultural positionalities…. but she appears to judge independent cinema and remote Aboriginal media associations more valuable, more worthy of both the title and state funding.[26]

The knock-on effects of dividing mainstream Aboriginal television makers from remote Aboriginal television makers significantly affected Aboriginal filmmakers to the extent that the National Indigenous Media Association of Australia (NIMAA) initially sought to ban Aborigines working in the ABC and SBS from membership (in 1991) because some felt that Aborigines working in mainstream television could not possibly be producing our own authentic Aboriginal programs [27].

From what I have seen of the Natives of New Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched People upon Earth; but in reality, they are far more happier than we Europeans, being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous, but with the necessary Conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them…The Earth and the Sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life. They covet not Magnificent Houses; Household stuff; they live in a Warm and fine Climate, and enjoy every Wholesome Air…in short, they seemed to set no Value upon anything of their own nor any one Article we could offer them. This in my opinion Argues, that they think themselves provided with all the necessarys of Life, and they have no Superfluities. Captain James Cook 1770 [28]

The patrons of nature’s gifts is perhaps the most common image of the noble savage to emerge in nature and wildlife documentaries. This is where audiences go on Whiteman walkabouts. Reflecting the early observations of Captain James Cook, who envied Aborigines for living in harmony with nature, numerous nature and wildlife documentary programs sustain the concept that only real Aborigines have a natural affinity to land, living like native flora and fauna, with no need for anything that exists in the modern world. Documentaries that have done this are Walkabout, the first documentary series on television featuring Aborigines, produced by Charles and Elsa Chauvel in 1958 and aired for 13 weeks on the ABC; and Vincent Serventy’s Nature Walkabout which ran for 26 weeks on the Nine network the same year. Both programs served a purpose that I think we have underestimated. The Nature Walkabout series followed Vincent Serventy and his young family travelling across the continent [29]. Continuing the same format, the Leyland Brothers World series went into production as early as 1961 for the Seven Network, producing over 40 episodes for the network throughout the 1970s [30]. A regular feature of Seven’s World Around Us series during the late 1970s was Malcolm Douglas’s Adventure series on the Seven Network, which mostly featured Aborigines who were almost invariably Douglas’s friends or guides.

In these films/programs, voiceless Aborigines, like other flora and fauna, are seen in nature and wildlife documentaries as backdrops. Their importance is that they can sometimes appear as the Aboriginal friend who enjoys passing on traditional knowledge to the White protagonists, who also live harmoniously with the land. The role of the White protagonist in nature and wildlife documentaries, as my mother would say, always looked somewhat unnatural in bare feet, pretending to be at one with nature, until they were able to reunite with an invisible camera-crew, a 4WD and a chartered flight back to some swanky Sydney editing room. Another friend of the Aborigines was Harry Butler, a Tasmanian naturalist and conservationist who became noted for his passionate interests in plants and animals. Harry Butler in the Wild (1976) was a popular 26-episode series produced by the ABC and repeated throughout the 1970s.

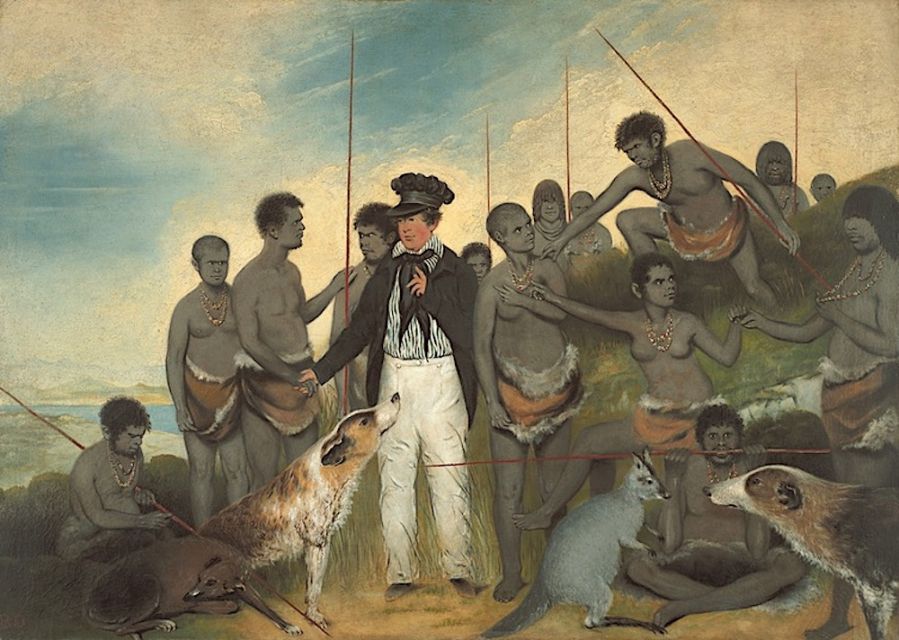

The Conciliation - Benjamin Duterrau 1840

Both Butler and crocodile farmer and filmmaker Douglas abandoned the family expedition format that was set earlier by Chauvel, Serventy and the Leyland Brothers, and made personality-driven protagonists a popular style.

Appearing on television in the 1980s, the ABC made a comeback on their nature and wildlife programs with the new highly popular series Bush Tucker Man. Les Hiddens, who played the Bush Tucker Man, was most noted for wearing army fatigues and a strangely modified Aussie slouch hat. An environmentalist like Butler, he had a more robust personality and was an expert in edible native plants and animals, sharing Sir Walter Raleigh’s fascination for the diets and eating habits of the native people. The series ran for 26 episodes and was repeated several times on the ABC.

The ‘Aboriginal friend’ theme of White-man storytelling has been cleverly parodied by Australian actor/comedian Glen Robbins who plays the part of Russell Coight. Appearing as Coight in an eight-part one-hour mockumentary series airing on Channel Ten, Coight travels and meets with Black and White people living in the outback, often describing people he meets as a best mate or an Aboriginal friend. Robbins demonstrates Coight’s exaggerated popularity amongst the locals. The point becomes even more inflated when Coight introduces the camera to his mates or friends who have a hard time remembering him. When Robbins edits the story together, we see a repeated close-up handshake between a Black hand and a White hand; but when a wide-shot appears we see Coight’s character shaking hands with White men only. In this way, Robbins is sending up one of Australia’s most iconic images, the close-up of the Black/White handshake, which is common in several films. It is even one of the main symbols of the Aboriginal Reconciliation movement in Australia, which was introduced by the Hawke government in 1991.

In all questions of morality and in all matters connected with the emotional nature the Blacks were mere children. C.S Wake [31]

Darwinians believed European adults passed through the stages of human evolution while growing up. They considered Aborigines were at the childhood stage. References to Aborigines as childish are too numerous to mention. The assumption that Aborigines are childlike underlines a reasoning for policy makers to think Aboriginal people are not ready to handle their own affairs, or incapable of becoming leaders of their own communities. Aboriginal barrister Noel Pearson argues that paternalism and welfare chains Aborigines to their own social and cultural demise and that Aboriginal people should be responsible for their own problems [32]. However, it is not that simple. There are more than a few reasons why Aboriginal people still need assistance and should be taking responsibility for our own affairs. This is not because we are childlike, but we are extremely disadvantaged economically, socially and politically. Until these issues are dealt with, we will continue to be seen as childlike dependants who are uncomplicated, while the dominant message of us as childlike continues to feed into the mythology that White people must remain in control of our affairs.

In 1964 a sixty-minute documentary presented by Aboriginal singer and Australian pop-star Jimmy Little called A Changing Race, made by non-Aboriginal filmmaker Robert Feeney, aired on ABC TV one year before the Freedom Rides [33]. What was ground-breaking about this film was that it gave Aborigines a voice in television. The presenter was Aboriginal and the people in the film who spoke were Aboriginal people talking directly about their own issues. Despite the impact it made at the time, the trend for White narration over Black images continued to dominate even until the 1980s where film and television makers used the White voice of god narration in their films. Critical of narration was ethnographic filmmaker Ian Dunlop who said it was a constant struggle to use narration and subtitles over the translations of one language to another and with the tidying-up Aboriginal Kriol; he therefore opted for his films to use no sound at all [34]. Since that time the trend has reversed and now filmmakers will only use Aboriginal people as narrators or presenters for films which have an Aboriginal subject [35].

Perhaps a most familiar representation of Aboriginal people in film and television is the use of alcoholism in the community, even though they do not address alcoholism with the White community to the same extent as they report Aboriginal alcoholism. Three films come to mind, they are Margaret Lattimore’s film Genocide (1990), Denis O’Rourke’s Couldn’t Be Fairer (1983) and David Bradbury’s State Of Shock (1989). In all three films, we view the problem of alcoholism and how it brings anything from violence to self-mutilation and the self-destruction of Aboriginal society, culture and tradition, and how it leads to deaths in custody. Such films show us Aboriginal men perpetuating violence against Aboriginal women even though they too are victims of colonisation, sending the message that while they are violent, they are also victims.

Films about the stolen generations are examples of portraying Aborigines as victims, where the children are taken solely because of racist policies and not for other reasons. Darlene Johnson’s film Stolen Generations (2000) is one and David MacDougall’s film Link-Up Diary (1987) is another. What is especially important about Johnson’s film is that it made an important statement at a crucial time in Australian political history – one month before the federal Member of Parliament for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, Senator Herron, challenged the notion of stolen generations. Link-Up founder and historian Peter Read stated at a 1999 Screensound Australia presentation that during the time they were filming in 1987, there were cases where they wanted to reunite people with their families, but some were not as enthusiastic about reconnecting with their Aboriginal heritage. He stated that he held the view that all Aboriginal children fostered out to White families were eager to reconnect with their heritage. This became a more popular view following the unveiling of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s 1997 Bringing Them Home Report. Whereas, in reality the reconnection to biological and cultural roots is not uncomplicated, and not every case of Aboriginal children being removed from their Aboriginal families is a case of being stolen on the basis of racist policies.

The point I am making here is that whether it is alcoholism, deaths in custody, women and domestic violence, stolen generations or reconnecting with family and culture, we as filmmakers have a responsibility to say more in our films about the complexities that exist in our communities and in the individual lives of Aboriginal people, and that we are not all innocent, and not all immoral either. I believe the reason we, as Aboriginal filmmakers, do not always address the complexities is because we anticipate misunderstanding from White audiences who are frequently incapable of accepting responsibility for the damage to which they have contributed. So, instead of feeling sympathy they move from one opposing pole to the other and blame Aboriginal people for their problems. This is not to say that we, as Aboriginal filmmakers, need to water down the message; rather, that we might want to work harder at presenting all the facts.

The long history of White guilt often rears its ugly head, shifts to the opposite pole of innocence, and emerges as blame or indeed denial. This was the case when Senator Herron, Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, tried undermining the Bringing Them Home Report on ABC TV’s 7.30 Report (3 April 2000). In this program, journalist Tim Lester reported that Herron stated ‘there was no such thing as a stolen generation’ simply because he thought there simply were not enough children taken to warrant that word ‘generation’ even though the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 gave them the authority to remove Aboriginal children without establishing in court that they were neglected 85 years prior. Historically, there have been some Whites who felt badly done by some Blacks, so they feel compelled to disproportionately retaliate. This can be seen in the attitudes of early 19th century colonial authorities who once romanticised Blacks and then wanted them eradicated. Woolmington argues that Aborigines were initially perceived as ‘virtuous’ until such time as they resisted the land grabs by new White settlers who grazed and cultivate the land and stole their children and women [36].

Another component of this is when Whites feel they are the victims of Black progress. Perhaps most publicly recorded was the screening of One Nation Party leader Pauline Hanson who in her maiden speech to parliament on 10 September 1996 stated:

Hasluck’s vision was of a single society in which racial emphases were rejected and social issues addressed. [And] … I totally agree with him, and so would the majority of Australians. But remember, when he gave his speech, he was talking about the privileges that White Australians were seen to be enjoying over Aboriginals. Today, 41 years later, I talk about the exact opposite — the privileges Aboriginals enjoy over other Australians.

It is interesting that Hanson quoted Hasluck since he was the father of the 1950s Aboriginal assimilation policies that gave impetus to the removal of Aboriginal children, and one of the most oppressive Ministers of Aboriginal Affairs. Whenever Aboriginal people show their upper moral hand, it is not always greeted with sympathy or acknowledgement; it can be met with resentment and retaliation, particularly when seen to receive support from Whites who are educated and progressive. On the other hand, there are some Whites who seem to take their ‘guilt’ to the opposite extreme, trying to take the blame for everything, even competing over who is the biggest victim, but that is a whole other story I will address at a later time.

They are ungrateful, deceitful, wily and treacherous. They are indolent in the extreme, squalid and filthy in their surroundings, as well as disgustingly unpure amongst themselves. W. Wilshire [37]

The idea of Aborigines as close to nature has its nasty savage side. During the 18th and 19th centuries, Aborigines were practically seen as non-human. The observations of artists and scientists were fraught with European double visions and value judgments, prejudices and discriminations, equating Aborigines as sub-human and animalistic. The examples of statements about Aborigines as possessing ape-like characteristics are abundant. During the 19th century Melanesian, Polynesian, Indian and Caribbean groups were also stigmatised with ape-like comparisons; however, it was thought the Blacker the skin colour the more animalistic the race. Therefore, Melanesian and Aboriginal people were less civilised than brown-skinned people like the Polynesians or Caribbean groups who were considered more attractive, intelligent, sociable and so on. Darwinian scholars and 19th century anatomical scientists extended their studies to the Australian Aborigines, brandishing Aboriginal society as not having sovereignty and being devoid of governance, law and civilization. Augustus Prinsep, in 1833, likened Aborigines to Orangutans. Roger Barthelemy’s drawings most resemble Aborigines with the features of apes and British Bulldogs. Leading medical scientist W. Ramsay-Smith, in his paper entitled ‘The Place of the Australian Aborigine in Recent Anthropological Research’, stated in 1907 that ‘Aborigines furnished the largest number of ape-like characters than of any other race’.

While Wilshire made this statement in a previous century, such views about Aboriginal people as being filthy, indolent and ungrateful were found to exist and fit in with the basic assumptions of White Australians in the 1950s by researcher Malcolm Calley in New South Wales. Calley found that many White Australians thought Aborigines were dirty and foul-smelling with no concept of hygiene, riddled with diseases and sexually promiscuous. Calley’s research also revealed that Whites believed Aborigines drank more alcohol than they did, and handled it badly. They also believed Aborigines were lazy, unpunctual, thriftless – unreliable characteristics compounded by an incessant gambling addiction – all of which proved they were mentally inferior to Whites [38]. Yet, what is so interesting in Calley’s report is that he conducted his research before television broadcasted in Australia, especially on the north coast of New South Wales, proving that such assumptions were already developed. More recently, we saw how the accusation of Aborigines living in squalor and filth appeared in the now infamous Sixty Minutes episode where Pauline Hanson asked Tracy Curro to ‘please explain’ the meaning of xenophobia [39].In this episode, Hanson visited the Aboriginal community on Palm Island, stating how difficult she found it to sympathise or want to do anything for Aborigines if they did not seem to care about the garbage and sanitary problem on the island. It is clear in the episode that Hanson is unable to differentiate between poverty and keeping tidy. In his article ‘Aboriginal Cannibalism’, media scholar Steve Mickler argues that comments made by Hanson and others claim that Aborigines should ‘earn their rights and entitlements by proving they have moral fitness and worthiness’.

The supposition that Aborigines have an innate desire for filth, indolence and are incapable of taking care of anything material, is embedded deep within the colonial consciousness. When conveying their values through colonial eyes, issues such as the need for land are so often inadequately communicated by film and television makers and those they interview. From the anti-land rights advertisement campaigns and the stereotypes of Aborigines as unproductive lazy brutes, very few Australians are able to understand what the land rights debate is. They instead imagine land rights in the 1970s as something that gives permission to groups of unemployed, lazy or apartheid-driven activists seeking to literally sit in the dirt and ‘dream’ of a culture that is lost [40]. Thirty years later, the stereotype is still present, so the question is: how should filmmakers address the issue today, especially when politicians remain unconvinced of Aborigines being capable of looking after land and being productive on it? This is indicated in a statement given by One Nation member David Oldfield, who stated in the New South Parliament as recently as the 4 December 2003:

‘I acknowledge that the Aboriginal people, as a people in the past, are an anthropological oddity and are no doubt significant and worthy of study. Perhaps the House should be reminded that prior to White settlement Aboriginal people, through their various practices, ignorant as they were, managed to wipe out approximately 500 species of flora and fauna, that is, make it extinct…And had White settlement not come along, what would the Aboriginal people be doing with the land today? They would be doing the same as they had always done, hunt, fish and set it on fire. Aboriginal people need us to help them make it into the twenty-first century.’ [41]

With notions that the land is our ‘mother’ (the origins of this concept are debatable [42]), it is little wonder that phrases such as ‘the land is my mother’ or comparing sacred sites to that of churches are concepts that are meaningless for many. I refer to a time when I screened a film to a group of students. In the film, one Aboriginal character compares the destruction of an Aboriginal sacred site to the destruction of St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. The feedback from one White student was that, while he admitted that he was a supporter of Aboriginal rights, he felt the analogy was unsatisfactory because he, like many others, would in fact be thrilled if St Mary’s Cathedral was destroyed, so such an analogy had little meaning for him. I left that afternoon thinking how important it was to be able to communicate ‘sacredness’ more effectively in films, rather than hooking onto catch phrases or rhetoric that may have worked 30 or more years ago.

A powerful film that tackled the issue of land and dispossession well at the time was Munda Nyringu, co-produced in 1983 by Jan Roberts and Robert Bropho, a Nyoongah man from Western Australia. It was a documentary about the Western Mining Corporation and the local Aboriginal people around Kalgoorlie. Images of traditional owners between shots of substandard housing conditions and the goldmines themselves, inter-cut with detailed graphics demonstrating the statistics of mining finances against the dispossessed Aborigines in the film. Although a personal favourite of mine, this film may not be so convincing today, or it could be accused of political correctness, which is a term that has become completely ambiguous and bandied about in the last decade or so. Another powerful film is Darlene Johnson’s Gulpilil, where Johnson carefully averts this problem, and we witness a combination of Gulpilil’s frustrations with not having land rights. We understand, through the film, that although fraught with hardships, it is a choice he has made to live on his mother and his father’s country.

It is little wonder that so many film and television makers try to make Aborigines worthy characters, using statements where Aboriginal people express themselves as feeling inferior to Whites. I quote from my own experience as a producer editing an interview with Aboriginal actor Pauline McLeod where McLeod stated, ‘If White people really knew Aboriginal people, they would learn to love us and see us as human beings’. The director, who was Indigenous, thought the statement was highly emotive, accurately represented what McLeod felt, and thought it would appeal to White audiences. I, on the other hand, cut the statement out because I did not think it was necessary to the story and it was embarrassing. Not so much embarrassing for her, but probably for me, because I had grown up hearing too many Aboriginal people in the media pleading for White approval and acceptance. Likewise, those Aboriginal people who still need an apology for the stolen generations, or those who feel it is their responsibility to reconcile with Whites. These are concepts I do not relate to but often hear used in documentaries about Aboriginal people. For example, in an episode of Art Review, renowned Indigenous actor Bob Maza was used to conclude the show by saying that he just wanted Aboriginal people to be equal with Whites [43]. Feeling annoyed with the statement, because I had heard it over and over again, I wrote to Art Review asking the producer to explain which White person she thought Maza was hoping to be equal to. My letter went on to say that I thought it was particularly patronising of the producer to use such a clichéd statement as this to end the segment, particularly since there were probably stronger statements that could have been used. The producer was indeed Aboriginal herself, and someone I had worked with in the past. Although it is unfair to blame filmmakers for the things Aboriginal people say in front of the camera, especially when the Aboriginal talent/subject, is imagining his/her audience, filmmakers are responsible for what is finally used in the film, and equally responsible for what gets left out.

Nakedness was another indication of Aboriginal people as creatures of the noble savage kind. It was an important feature for artists and writers to record. John Hawksworth wrote in 1773, 'All inhabitants that we saw were stark naked, they did not appear to be numerous nor to live in societies, but like the other animals were scattered along the coast and in the woods' [44]. Nakedness of Black and brown bodies, closed off from sexual voyeurism, is tolerable if discussed in a cultural context and available to be discussed openly in a non-sexual context, since observers would never admit to their own sexual desires. For example, where photographer Kolodny removed the tops of Aboriginal women’s dresses to reveal their breasts, Kolodny justified it as being simply to accentuate their racial differences [45]. Likewise, Leni Riefenstahl, who strongly argued her films had not been the visual-architect of Nazi aesthetics, also denied her erotic voyeurism of Black nakedness when she portrayed Nubian men of Africa [46].

From the early 18th century, the issue of skin colour oscillated between the noble and savage poles. At the turn of the 19th century, colonists began romanticising the Black-skinned Aborigines as the pure and authentic noble bushman, and ‘hybrids’ carried the bad in both White and Black races [47]. Where Black-skinned Melanesians were considered more savage than brown-skinned Polynesians, the civil rights movement and the rise of the Black Panther movement of the 1960s espoused slogans of ‘Black is beautiful’. In an Australian context, Black skin has since become nobler and brown skin more treacherous. Black (or very dark) skin is not as publicly visible in Australia as it is in the United States or the United Kingdom. White or fair-skinned Aborigines are barely tolerable in Australia because we are aware of the extent to which ‘full-blooded’ Aborigines have been deliberately interbred with White people as a part of the assimilation policies. Having established that, it is now the fair skinned Blacks who are perceived as the savage ones, and who are most likely to be associated with treachery and inauthenticity. Such is the case for Tasmanian Aborigines accused of not being Aboriginal enough because they have blond hair and blue eyes [48]. Once, the ‘full-blood’ Aborigine was regarded as treacherous on the frontiers of settlement, but the ‘mixed-race’ Aborigines have since replaced them, and sympathy goes to the ‘real’ dark-skinned Aborigines because they are becoming extinct.

Where the camera’s lens confines people with Black skin to a traditional cultural or environmental context, rarely do we see them in kitchens, or in public spaces like coffee shops and supermarkets, going to work in their offices or in the ordinariness of the day. Aboriginal people with fairer coloured skin or brown skin, on the other hand, are not restricted to the same environments, but it is still unusual to see brown-skinned people in a non-political or cultural context. Black people or brown people supposedly do not occupy the same public sphere as White people, which is why I made my film Oceans Apart (1991). In this film, I place Aboriginal women in the public sphere like railway stations, classrooms, sipping tea in the dining room and so on. The film was a response to a comment I heard from someone who lived in Bondi saying she had never seen an Aboriginal person. I imagined that her oversight was because she had been unused to recognising what an Aboriginal person looked like outside of her stereotypical visual imagination.

People with Black skins are often not from an English-speaking background. Those with brown or fairer skins often are. Black-skinned people are seen with narration or subtitles. Brown or fairer skinned-people are sometimes seen as subtitled, but they are generally seen to have a slightly better command of the English language. From my experience, as someone who has worked in radio, I have always found the tone of the male Aboriginal voice generally softer than White men’s voices; however, non-Aboriginal people are less likely to hear or distinguish an Aboriginal accent. They are more able to understand an American accent than an Aboriginal accent. Aboriginal people are able to tell where a person comes from even if they are speaking Aboriginal English [49]. In any case, it is still difficult for non-Aborigines to appreciate the Aboriginal voice, in much the same way that female broadcasters try to give authority to their voices by lowering their tone to sound more like men.

The matter of triumphing over the stereotype of Aborigines as Black naked brutes is perhaps a long way off. Nevertheless, I hope that what can be achieved in the long term is that stories about Aborigines can be just made as personally, honestly and confidently in spite of the racist blatherings from folks like Oldfield, Hanson and many others in the public domain. And that we continue to tell our stories while being mindful of trying not to waste our energies on counteracting racist stereotypes, or presenting ourselves as perfect human beings worthy of White acceptance.

Another enduring theme in noble savage literature is the idea of the tortured savage torn between two cultures. Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627), Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) all depicted ‘modern men’ (White men) struggling to learn humility and tolerance for their fellow but outcast (savage) ‘brother’. The tortured savage is an anti-hero but befriends White men, who ultimately betray or try to save or convert him, the savage always driven to extreme measures usually ending in his/her demise. This classic dramatic format from 18th century literature continues and is used in many films about Aborigines, who are always ‘torn’ between two cultures and loyalties. In William Thomas Moncrieff’s 1831 operatic three-act dramatic tragedy Oh Van Dieman’s Land! an Aboriginal woman, Kangaree, is torn between choosing the love of a White man over the love of a Black man. A century and a half later, feature films like Bruce Beresford’s Fringe Dwellers (1986), Charles Chauvel’s Jedda (1955), Fred Schepisi’s, Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith (1978), Henri Safran’s Storm Boy (1976), James Ricketson’s Blackfellas and Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971) all highlight Aboriginal characters who are torn between cultures.

Augustus Earle, Natives Of New South Wales In The Streets Of Sydney – 1830

The notion of Aborigines being torn between cultures acts as the explanation for the demise of the Aboriginal characters, instead of portraying a situation where the Whites themselves take an active role in their doom. Rather than accept responsibility, it is easier to blame Blacks for being lost between two worlds. Furthermore, this is problematic for Blacks only; it is irrelevant to Whites. Whites theoretically do not move between two worlds, but seem to be capable of accommodating and integrating their pasts and futures, good and evil, positives and negatives, without dying or losing their values, identities and lives. Whites think themselves capable of living within a multicultural society while maintaining their whiteness. It is only non-Whites who supposedly do not know how to do this. Only Aborigines are supposedly traumatised and diminished by integration, interaction and assimilation. If they do accommodate and integrate different cultures successfully, then they are not authentically Aboriginal. They become polluted or contaminated. Aboriginality when polluted dies, and so does the Aboriginal character or signifier in these plays and films. One example of non-fiction films focusing on the ‘two worlds’ theme is Curtis Levy’s Sons of Namatjira (1975).

While Desiderius Erasmus wrote of the ‘happiness of the simpleton and blockhead for they are devoid of knowledge of their own death’ as early as the 16th century, Australian writers in the 19th century thought Aboriginal people were doomed for extinction. As Henry Reynolds points out, writers of that time used an abundance of metaphors to describe Aboriginal people as variously fading away, fading out, decaying, slipping from life’s platform, melting away like the snow from the mountains at the approach of spring, perishing as does the autumnal grass before a bush fire. Reflective of Keith Windschuttle’s claims that more Aborigines were killed by natural causes than warfare, Herman Merivale argued in 1839 that the declining Aboriginal population was not due to warfare, spirits, new epidemics or the destruction of game. There were ‘deeper and more mysterious causes at work; the mere contact of Europeans is fatal to him in some unknown manner’ [50]. It is remarkable that Windschuttle and Merivale should find it more uplifting if Aborigines are killed by disease or prostitution than musket fire. Herman Merivale’s view that the disappearance of Blacks (or Black skin) is oddly enough mysteriously echoed in the 1993 documentary Black Man’s House. Steven Thomas’ film focuses on a group of contemporary Tasmanian Aborigines searching for their ancestors’ graves so that the ancestors could be finally put to rest in a culturally appropriate manner, at the Wybalenna cemetery. When this occasion takes place, it is perhaps the most uplifting and high-spirited moment of the film. For the rest of the film Tasmanian Aborigines are presented as morbid people whose skin-colour is not the same as that of their ancestors. The fiery and political savvy of well-known fair-skinned Tasmanian Aborigines like Jimmy Everett (who is in the film) is notably missing. This is a film where Thomas also uses the fair skin of the people in the film to his advantage, making a connection to White audiences. The music described as a funeral dirge is continuous, and stories of the Aborigines juxtaposed against a repetitious graphic of Benjamin Dutterau’s 19th century painting of the ‘Conciliator’ of George Augustus Robinson shaking hands with the natives at Wybalenna in 1840. Each time the graphic appears, the camera zooms further and further into the clasping Black/White handshake. This handshake, that I mention earlier, has become a powerful symbol in the Reconciliation movement, but nonetheless, represents unwritten negotiations between Black and White men or ‘mates’ only. Despite my interpretations of the film, Black Man’s Houses took out the award for best documentary at the Sydney and Melbourne Film Festivals. Also nominated for best documentary at the Australian Film Institute Awards in 1997 was Matthew Kelly’s Last of the Nomads (1997) in the classic style of Daisy Bates’ Passing of the Aborigines. This film follows five White men, led by an Aboriginal friend, into an uncharted Western Gibson Desert to locate two elderly members of the Mandildjara tribe, Warri and Yatungka, who of course eventually die after coming into contact with White society. Reflective of their anthropological lens to preserve culture from extinction and doom, the amount of their research on central and northern Australia vastly outweighs what happens in the more populated areas of Australia. Apart from Tracy Moffatt or Rachel Perkins, very few have written about Aboriginal filmmakers elsewhere. This is why I found the work by Faye Ginsburg encouraging because she had the imagination to write about us at the ABC when we were producing more Aboriginal documentaries per year than anywhere else. In this Ginsburg asks us, her readers from the Anthropological Review, to bear consideration for those of us already working in mainstream television [51].

Filmmakers whose preferences are for recording traditional culture still dominate the number of films made about Aboriginal people. Finding material on southern and eastern Aboriginal filmmaking is much more difficult. For example, the audio-visual archives in the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), although one of the world’s most recognised collectors of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander film and video with just over 1623 items, mostly focus on the remote regions of Australia or films that have been produced by scholars. While this is standard for any library, my concern is that for anyone conducting research on Aboriginal television produced by and about Aborigines living in urban communities, AIATSIS will not be the best option, although it ought to be since it is a very costly process to purchase archives from broadcasters. It is not an isolated case; in fact, the archives at Film Australia, which is primarily a production house, store more than 178 films currently catalogued under Indigenous films, which includes 44 films on Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Yet 82 of the 134 films feature central and northern Australia, and the remaining 52 films are divided into biographies or other films that are non-specific to location and/or feature urban Aboriginal life.

Of the 1819 items catalogued in Mura at AIATSIS, there are only 10 that were produced by Aboriginal producers at the ABC. Although the ABC archives hold more than 19,500 items on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories, and SBS holds more than 2000 items, AIATSIS only holds one documentary program that has been produced by the Aboriginal Programs Unit (APU) and three programs from the Blood Brothers series that screened on SBS TV. Therefore, the majority of the ABC programs are produced by White filmmakers and journalists and include news and current affair programs such as Four Corners and Chequerboard. Nevertheless, AIATSIS holds 26 copies of the ATSIC-funded Aboriginal Australia program, produced by Aboriginal producers Trevor Ellis and Karla Vista at the National Recording Studio in Canberra. Screensound Australia, on the other hand, boasts an Indigenous catalogue of 12,000 items although more than two thirds are stories about Aborigines living in remote regions. They hold ten series of ICAM (Indigenous Cultural Magazine programs) from 1996 to 2001, produced by the Indigenous Programs Unit at SBS, made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers.

Blackout II, 1989, Back Row L-R, Daniel Bobongie, David Sandy, Lorraine Wallace, Frances Peters-Little, Lorraine Mafi Williams. Front Row L-R, Susan Moylan Coombs & Bruno DeVillenoisy.

Other series produced by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teams in the APUs at the ABC and SBS were Blackout 1–7, First in Line, ICAM, Kam Yarn, Messagestick, Storytellers of the Pacific, Living Black and Songlines. Blackout ran for seven years, producing over 60 episodes. First in Line produced over 22 programs for SBS. The ICAM series on SBS ran from 1996 to 2002. Kam Yarn ran two seasons (1994–95), other mini-series like Songlines ran nine episodes, and the Storytellers of the Pacific in 1995 was a four one-hour international documentary series. In addition to this, the Many Nations One People series in 2001 ran eight episodes, and SBS commenced its first season of the dynamic Living Black program in April 2003. Messagestick, which began in 1999, continues to produce and air between 12 and 33 programs per year and operate an online service called by the same name.

Given that the Indigenous units at the ABC and SBS have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander producers and directors, one can see that there are literally hundreds of films and videos being produced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living and working in film and television in the southern and eastern states. And what is more interesting is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers in the southern and eastern states are less concerned about making films about preserving and recording a ‘dying’ culture; rather, they are interested in social, historical and political injustices. It is as if stories about Aborigines in the north are nobler stories about a race that is doomed for extinction, while stories in the southeast are about Aborigines who are savage and belligerent.

In terms of reading material, the vast majority of the 158 articles catalogued by AIATSIS under the heading of Aboriginal television, focus mainly on Aboriginal television in central Australia even though the majority of programs are produced by urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers working for mainstream television [52]. Of the total number of articles listed in the Murdoch Reading Room bibliography of Aboriginal television, the overwhelming majority of articles also emphasise a focus on community television in remote northern and central Australia. So clearly, resources for Aboriginal film or television making in the southern and eastern states are limited. Even though the number of films and people in urban centres in constant production is to some extent higher than the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people making films in the remote areas, one wonders what scholars are writing about and more precisely, what they are not writing about and why this should be the case.

Initially, I set out to review some of the most popular misconceptions and preconceptions of Aboriginal film and television making. I was intrigued by the noble focus on the ‘real’ Aborigines in northern and central Australia. I was concerned that there were perhaps too many expectations on Aboriginal film and television makers to prove that they could make different or better films about Aborigines than White filmmakers. That such expectations were being placed on us to prove that we supposedly possessed a natural ability to not only make films, but ones that could communicate more effectively to White audiences and offer a less political, unbiased, and even homogeneous view of Aborigines. I was concerned that the demand placed upon us as Aboriginal filmmakers would be that we were able to demonstrate our ‘natural’ abilities to our peers in broadcasting, academia, social and cultural theory and art criticism, and that expectations were being placed upon us to be able to represent our culture, community, history and political view for a pan-Aboriginality.

I was also concerned as to whether the political opinion expressed on television in the past was going to be better in the future as I examined those programs that were made in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly those which covered Land Rights, uranium mining and the 1967 Referendum. I was not especially convinced that the argument that we, as Aboriginal people, and our issues were as ‘invisible’ as some might claim [53].

I also take issue with the suggestion that television is getting better and that the political messages coming from the Aboriginal community were totally misrepresented in programs in the 1970s and 1980s, programs produced by White filmmakers such as the ABC’s Countrywide, Monday Conference, This Day Tonight, A Big Country, Weekend Magazine, Four Corners and Chequerboard. In fact, programs such as these specifically aimed to prick the conscience of comfortable White Australia. It was a time when journalism on the ABC (where I worked) did not support the view of Australia as the lucky country; rather, it found poverty, loneliness, neurosis, corruption, mental and physical suffering and other social problems just below the surface of everyday life. It covered many Aboriginal issues, focusing on Aboriginal land rights, the Bi-centenary, civil liberties and deaths in custody to name a few. Today there are fewer collaborative works than there were during the 1980s, which was a honeymoon period for independent Aboriginal documentary filmmaking, when filmmakers emerged from the Sydney Filmmakers Coop and made films like My Survival as an Aborigine, Lousy Little Sixpence, Munda Nyuringu, Couldn’t Be Fairer, Ningla A Na, Wrong Side of the Road, On Sacred Ground, State of Shock and Dirt Cheap.

It is problematic when we find ourselves swinging between the noble and savage poles of Aboriginal filmmaking. What I think we need to be seeking is a truth, or as close as we can get, in our storytelling. We need to be open to the opportunities of further honest and rigorous debate between ourselves and others, and find new ways of imagining and exploring ourselves. However, I feel that we have come to a point in Aboriginal filmmaking when we are facing the possibilities of strangling our creative processes. This is due to the latest surge of semi-legal protocols and guidelines that tell filmmakers how to culturally respect Aboriginal people, even to the extent of knowing how to read ‘Aboriginal body language’ [54] – a subject which I expand on in my 2002 article ‘The Impossibility of pleasing everybody: a legitimate role for white filmmakers making black films’ [55]. My concern is that with too many rigorous ethical protocols and cultural guidelines intended to protect Aboriginal ‘moral fitness and standards’ we run the risk of manipulating filmmakers to produce sanitised versions of Aboriginal culture, thus distorting the very culture they purport to protect. We have swapped the savage for the noble in a way that is neither true nor useful, and what we are perhaps witnessing is a savage backlash to years of noblising Aborigines as untouchable subjects. I am concerned about how this may affect the way I make films in the future. I am worried about how this may impact the way I approach people if I want to be critical of them and if I am prevented from saying anything new. I have struggled hard to understand where these noble and savage stereotypes of Aboriginal people come from. I am afraid I can see the damage that they have done, and I wonder if I still have any place in making documentary films in the future. But let us hope that will not happen, and that we can say in the future that we did not lack the courage to challenge ourselves, and others.

Footnotes

Peters-Little, F. (2002) ‘On the impossibility of pleasing everyone: the legitimate role of white film- makers making black films’, Art Monthly 149: pp5–9.

Hinkson, M. (2002) 'New Media Projects At Yuendumu: Inter-cultural engagement and self-determination in an era of accelerated globalization', Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 16:2, 201-220

Ginsburg, F. (1993) 'Station Identification: The Aboriginal Programs Unit Of The Australian Broadcasting Corporation', Visual Anthropological Review, Volume 9 Number 2 Fall 1993, p. 92.

Langton M, 1993, Well I Heard It on the Radio, and I Saw It on the Television, Australian Film Commission, Sydney.

McCullough M, 1995, Re-positioning Aboriginality: The Films of Frances Peters and Tracey Moffatt, Master of Arts thesis (unpublished), Department of Anthropology, New York University, p. 15.

Rousseau JJ, 1773, The social contract and discourses, cited by Gibson, R. (1984) The diminishing paradise: changing literary perceptions of Australia, Sydney: Sirius Books - p144.

Peters-Little, F. (forthcoming) The return of the Noble Savage: by popular demand, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

Foley, G. (1999), ‘Koori engagement with television’, Gary Foley’s Koori history website, Melbourne.

Langton M, 1993: 27-28.

Laseur, C. (1993) BeDevil: Colonial Images, Aboriginal Memories - originally published in Span, no 37, p4.

Bayles, T. (1989) 'We Live with the Problems,We know the Solutions' - Frank Archibald Memorial Lecture No 4, delivered 16 October, 1989, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Philip Batty talked about resistance model in: Batty, P. (2001) "Enlisting the Aboriginal subject: the state invention of Aboriginal broadcasting." Paper given at the ‘Power of knowledge, the resonance of tradition’, AIATSIS Conference, 18-20 September, Australian National University, Canberra.

The issue of what is a ‘real’ Aboriginal film is an issue that continues to divide Aboriginal film and television makers. For example, filmmaker Darlene Johnson who pointed out that her documentary The Making of Rabbit Proof Fence was excluded from an Indigenous film festival in Adelaide in March 2002 on the basis that the film was about a ‘white’ filmmaker. Johnson’s film was excluded even though Darlene is Aboriginal, and the subject was about Aboriginal actors in the film.

Barthes, R. (1973) Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers, London: Granada.

In chapter 3 of my forthcoming book, The return of the Noble Savage: by popular demand, I argue how funding and training becomes available for Aboriginal productions, what is being made, and for who it is being made for.

This parallels nature and wildlife studies/programs about Aboriginal hunters and gatherers where there is a White presenter/protagonist who studies the diets and cooking skills of Aborigines. See following discussion.

Dryden J, The Conquest of Granada, Part One, 1670, cited in Jones, R. (1985), ‘Ordering the Landscape’, in Donaldson, I & T (eds), Seeing the First Australians, Sydney: Allen and Unwin - pp181–209.

Cranston, M. (1991), The Noble Savage: Jean Jacques Rousseau, 1754-1762, London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press. See also Schaer R, Claeys G, and Sargent LT (eds) (2000), Utopia: the search for the ideal society in the western world, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Both books stress in great detail many complex reasons for European desires for utopia and the noble savage in several European societies throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

Discussions arising at the Cross-cultural Round Table, convened by David and Judith MacDougall, Braidwood, New South Wales, February 2000.

Peters-Little F. Interview with Alec Morgan, Bondi Beach, November 2001.

For example, the film Malangi is a documentary I researched for Aboriginal director Michael Riley, about ‘a day in the life’ of Aboriginal artist David Malangi, who starts the day hunting and gathering with his extended family. On the shoot, Riley discussed how he was particularly fascinated with the traditional lifestyle but was somewhat pleased that his own life was not as hard going in Sydney where he lived and worked.

Gibson, R (1984), The diminishing paradise: changing literary perceptions of Australia, Sirius Books, Sydney - pp2-3

Thomas, N. & Losche, D. (eds) (1999) Double Vision: Art Histories and Colonial Histories in the Pacific, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, T (1994) ‘When Australia became modern’, Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media and Culture, 8(2).

McCullough M, 1995: 15.

Peters-Little F. Interview with former secretary of NIMAA, Greg Eatock, Sydney, 2001.

Cook J, the Journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery, cited in Reynolds, H. (1987) Frontier: Aborigines, settlers and land, Sydney: Allen & Unwin - p96.

Peters-Little F. Interviews with Catherine Serventy, one of the children on the Serventy series, November 2001.

Peters-Little F. Conversation with Seven Network’s archivist.

Wake CS, The mental characteristics of primitive man, as exemplified by the Australian Aborigines, 1872, cited in Reynolds 1987: 118.

Pearson, N. (2000), Our Right to Take Responsibility, Cairns, Qld. : Noel Pearson and Associates.

Borchers, W. (2001), ‘Aboriginal archives at the ABC’, a paper presented to the ‘Alternative Australias’ symposium, Shine Dome, Academy of Science, Canberra.

Dunlop I. Round Table discussion at Cross-Cultural Filmmakers Conference, Braidwood, 2000.

For example Sean Kennedy, director of Jimmy Little’s Gentle Journey, 2003, who insisted on using Aaron Pederson for narration.