What’s Wrong with this Picture?

Personal Reflections on Developments in Indigenous Media in Australia, by Philip Batty

It is with mixed feelings that I delve into my past involvement in the early development of Indigenous media in Australia. The commitment that many of us devoted to making a space for Aboriginal people in the nation's media landscape appears to have been spectacularly successful. Yet it seems to me that the benefits this was expected to bring have fallen short of what was originally envisioned. Of particular concern is the fact that the most disadvantaged sector of the Indigenous community - the people at whom these efforts were, in my view, primarily directed - have seen little improvement in their general well-being. One finds the same anomalous situation in almost every other area of Aboriginal Australia. Despite more than forty five years of herculean efforts to remedy the poor living conditions of Australia's first peoples, many indexes measuring Indigenous well-being continue to show a persistent lack of advancement and in some areas, a steady deterioration.

Cemetery at a remote Aboriginal community in Central Australia, 2016

As I write this article (August, 2021), numerous government reports paint an exceedingly gloomy picture of Indigenous life in Australia. They show, along with other confronting data, that rates of Aboriginal suicide and self-harm have increased 40% in the ten years to 2018 [1] that in 2017, 27% of prisoners in Australian jails were Indigenous, while they were 2.0% of the population, making them the most imprisoned people in the world [2]. These, and other alarming statistics are, of course, indicative of deeper social pathologies. For instance, in 2014-15, Aboriginal women were 32 times more likely to be hospitalized than non-Aboriginal women as a result of domestic violence [3]. Alcohol abuse in the Aboriginal community has become such a problem in towns like Alice Springs that draconian regulations akin to those abolished in the 1960s have been reintroduced in an attempt to restrict the sale of alcohol to Aboriginal people [4]. Indeed, such is the seriousness of the problem, these harsh regulations have been endorsed by the leading Aboriginal medical service in the town [5]. Other depressing surveys in the areas of health, education, employment and other sectors depict a similar outlook.

These appalling figures may suggest that successive Australian governments have been neglectful, if not actively oppressive of Aboriginal people. This is not the case. Since the mid 1970s land rights and native title legislation have given Aboriginal people ownership of, or a direct interest in, close to 40% of the nation's landmass [6]. In the 2015-16 financial year, the government's Productivity Commission found that direct government expenditure on Indigenous people was $33.4 billion [7]. This amounted to $44,886 for every individual Aboriginal person, which was twice that of non-Aboriginal Australians, at $22,356.

Similar support has been directed at Aboriginal media organisations. Since 1980, Aboriginal-owned radio stations have been established in almost every Australian state; more than a hundred remote Aboriginal communities operate their own media services; the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) feature numerous programs by and about Aboriginal people; award-winning Indigenous filmmakers proliferate, and unlike any other single group in the country, Aboriginal people are now the beneficiaries of a national television network (NITV) catering exclusively to their needs and interests. Yet, the disastrous outcomes in Aboriginal Australia continue.

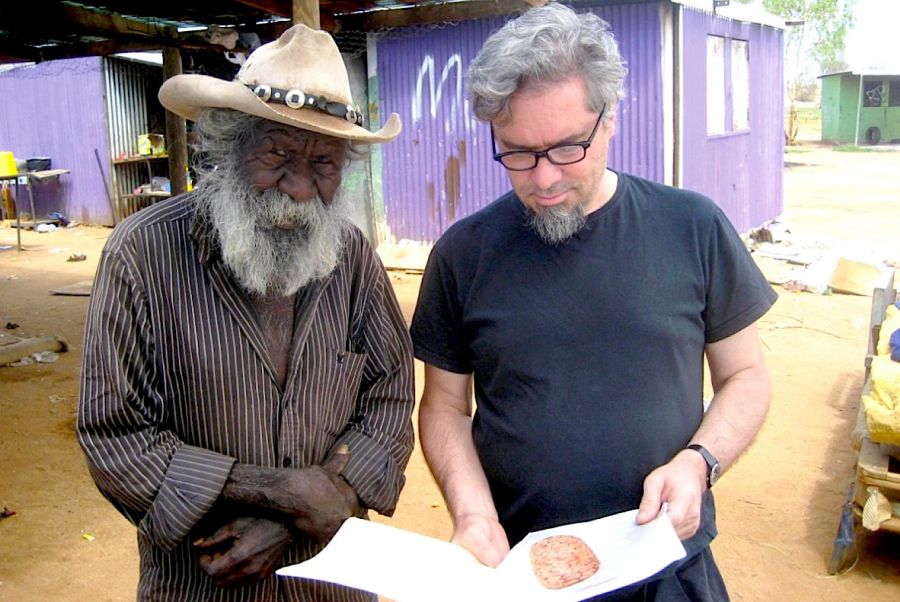

Patrick Hayes Kemarre & Philip Batty, during research for Reconstructing the Spencer and Gillen Collection Online (2014) ©Jason Gibson

It may appear somewhat out of place to be raising the problem of persistent Aboriginal disadvantage in an essay focused on a retrospective account of Aboriginal media in Australia. However, it is an unfortunate fact that the regions in which such media services have been in operation for the longest continuous period are the same regions in which Aboriginal disadvantage has seen the least improvement. For instance, on a percentage basis, the highest rates of incarceration amongst Aboriginal youth can still be found in the Northern Territory [8], yet it was in the Territory that the first Aboriginal-owned radio station was established (8KIN-FM) and the only region in Australia where a satellite service owned by an Aboriginal company (Imparja TV) was established and still operates. What makes this conundrum particularly galling for me, is that I was intimately involved in the development of these services (see below).

Such stark anomalies provoke a number of painful questions and undermine much of what I once considered self-evidently true. Most importantly - and perhaps most naively - I had always believed that if Aboriginal people had 'control' over their own media it would help improve their general well-being, particularly in the area of mental health. With the ability to represent themselves; to see their own people and to hear their own languages, would, I thought, improve their lives immeasurably. Unfortunately, in places such as the Territory, the reverse appears to be the case, and while there are many factors contributing to the ongoing problems in Aboriginal communities, one would have expected that the provision of comprehensive media services would have gone some way in remedying such problems.

Moreover, with the widespread up-take of smartphones in Indigenous communities throughout the Territory, Aboriginal people now have a far greater ability to 'represent themselves' in the media. Like millions of others on the planet, they regularly use a variety of social media platforms to post a vast stream of images, videos and messages, about themselves, often in their own languages. And like all smartphone users, they 'control' the filming, editing and presentation of this material which of course, is available across the globe.

So what is wrong with this picture? Why, after such great advances in the implementation of Aboriginal radio and television services across Australia including the pervasive use of social media - coupled with decades of government support in many other areas - does poverty and dysfunction remain a daily reality for large sections of the Aboriginal community?

Some have argued that this calamity can be attributed to the change in government policy, spearheaded in 2007 by the federal government's so-called 'intervention' in the Northern Territory, or formally, the Northern Territory Emergency Response [9]. According to this view, the deterioration in Aboriginal Australia began when the government's previous policy of so-called 'Aboriginal self-determination' was dropped and replaced with what these critics have dubbed 'neo-assimilation', implying that Aboriginal people were much better off before the 'intervention'. This is entirely erroneous.

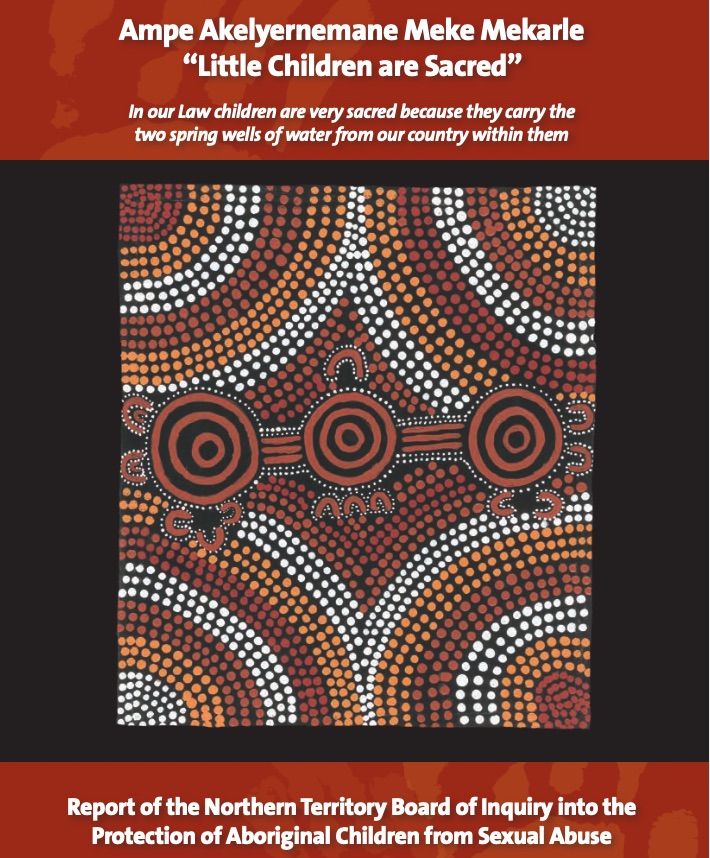

Cover of the Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, (© Northern Territory Government, 2007)

Briefly, the 'intervention' was sparked by a report commissioned by the Territory government into child sexual abuse in Aboriginal communities [10]. The primary investigators were Aboriginal human rights advocate, Pat Anderson AO and the former Director of Public Prosecutions in the Territory, Rex Wild AO QC. Among many other findings they stated that:

The classic indicia of children likely to suffer neglect, abuse and/or sexual abuse are, unfortunately, particularly apparent in Aboriginal communities. Family dysfunctionality, as a catch-all phrase, reflects and encompasses problems of alcohol and drug abuse, poverty, housing shortages, unemployment and the like. All of these issues exist in many Aboriginal communities. [11]

While the federal and Territory governments response to the report - 'the intervention' - was indeed heavy-handed, clumsy and ineffectual, to suggest that the situation in Aboriginal communities was fine before the intervention is ludicrous, as the above quote makes abundantly and tragically clear. Rather than acknowledging the dreadful situation uncovered by the report, those who attacked the government's response were more interested in using it as an occasion to rattle their ideological can and sing nostalgic paeans to the failed policies of 'aboriginal self-determination'.

In fact, for a large section of the Aboriginal community, their well-being began to deteriorate after the introduction of 'Aboriginal self-determination' polices, not as a result of the 'intervention'. For instance, from 1981, just a few years after the implementation of these policies, Aboriginal suicide rates began to steadily increase and have continued to do so up to the appalling levels we see today. According to research published in the Medical Journal of Australia, between 1981 and 2002, suicide among Aboriginal men increased by a staggering 800%. [12]. The same can be said for rates of Aboriginal incarceration. Before the 1970s, suicide was practically unheard of in Aboriginal communities and proportionally, Australian prisons held fewer Aboriginal inmates.

In this essay, I try to address these and other anomalies and the uncomfortable questions they must necessarily provoke in anyone concerned about the future of Aboriginal people. But I do not expect to provide any definitive answers. My aim is to simply point to the possible reasons why we have arrived at this disheartening point in time with the hope of finding some clarity and a means of moving forward. Indeed, I am compelled to make these enquiries for the same reasons I initially became involved in the implementation of Aboriginal media; to play a part in improving the lot of Aboriginal Australians. I will begin by providing an overview of that involvement. Hopefully this will offer a broader context in which I address these anomalies and also, why and how I have arrived at my current viewpoint.

In early 1977, I went to work as a teacher at the remote Aboriginal community of Papunya in Central Australia, located some 320 kilometres west of Alice Springs. At the time, there was a great deal of optimism about the future prospects for Aboriginal people throughout Australia and in the Northern Territory in particular. A veritable revolution in Aboriginal affairs had taken place just before my arrival. The Whitlam Labor Government (1972-1975) had swept away the old bureaucracy that had administered Aboriginal affairs in the Territory since the early 1950s and replaced it with a plethora of new programs and innovative legislative actions. Most significantly, the N.T. Land Rights Act had returned vast tracts of land to traditional owners and created Aboriginal land councils with strong statutory powers that eventually led to 50% of the Northern Territory returning to Aboriginal ownership, and another 17% through Native Title legislation. [13]. With such significant control of these lands and its vast resources, along with all the other reforms, there was a confident expectation that Aboriginal people could build a bright future. It seemed that the former oppression, disadvantage, and enduring poverty of Aboriginal people was well and truly over.

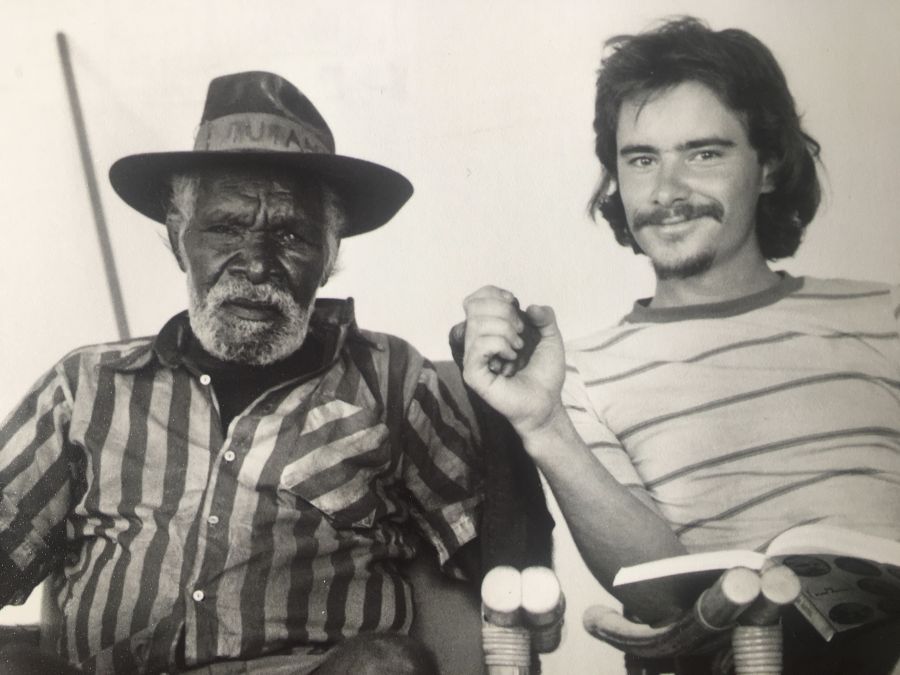

Tutama Tjapangati and Philip Batty. Papunya, Northern Territory, Australia, 1978

For a young white teacher like myself who had come of age during the Vietnam war - and participated in numerous anti-war demonstrations and radical student politics - the 'revolution' taking place in the Northern Territory was heady stuff. Aboriginal 'community-controlled' organisations were rapidly emerging throughout the region, including legal-aid services, housing cooperatives, medical clinics, independent schools and other bodies. What I found particularly inspiring was the fact that the formation of these organisations was largely led through partnerships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. A number of white lawyers, doctors, teachers, anthropologists, architects, film makers and activists, had arrived in the Territory from across Australia to work with local Aboriginal people to build a network of independent Aboriginal bodies. It was indeed fertile ground for radical indicatives.

I had always had a strong interest in the politics and theory of mass media and had participated, to a limited extent, in 'video access' centres in Melbourne during the early 1970s. After arriving in Central Australia, where the regional Aboriginal population was then well over 50% of the total, the complete absence any relevant media services for this sizable local audience, particularly in their own languages, was, for me, an injustice. This omission was made particularly apparent while I was working at Papunya where whitefellas like me made up about 2% of the local population, yet enjoyed 100% of the available media (albeit, through short-wave radio services and aircraft-delivered newspapers).

In 1978, a group of government officials arrived at the community to talk to local Aboriginal people about the forthcoming national satellite, AUSSAT. As with similar delegations about government initiatives, the information about this new technology was presented in formal English with no attempt to make the complexities of satellite communications explicable to a people who were for the most part, illiterate, with limited, or in some cases, no English. Indeed, a number of Aboriginal residents had only made 'first contact' with white people in the 1950s and 60s. Not surprisingly, very few local Aboriginal people turned up to listen to the delegation. Not only was this presentation on AUSSAT next to useless, it seemed obvious to me that beaming in city-based television directly into remote communities such as Papunya, without any level of local mediation, would have a profoundly negative impact on local languages and other cultural aspects of these isolated Indigenous societies. Along with a few other whitefellas, I pointed this out to the officials, but it did not seem to make much impression on them. They basically saw satellite services as an infrastructure issue, like the provision of water, electricity or surfaced roads.

I remember being so fired-up by the total lack of preparation for the impending avalanche of 'whitefella television' into Papunya and other communities, that I came up with a modest proposal to create a local media service to counter the satellite, or at least, to provide a glimpse of how such media might be possible. Working after school hours with some of my Aboriginal students, we put an audio program together on an ancient reel-to-reel tape recorder. It contained news and stories in the Aboriginal languages of Papunya and some very rough recordings of emerging local rock bands. The finished program was copied onto thirty or so cassette tapes and distributed around the community, where privately owned cassette-players were easily accessible. This went down reasonably well, especially among the local teenage population who enjoyed the music and the amusing stories their peers had contributed.

My small experiment with the cassette-tape program raised some interest in the Northern Territory Education of Department. After leaving Papunya at the end of 1979, I was asked by the department to participate in a pilot project run by their adult education section. Initiated by a far-sited senior departmental officer, Chris Majewski, it involved the production of a half-hour radio program for Aboriginal people in Alice Springs. Broadcast on Sunday nights, it was called the Aboriginal Half Hour. The local commercial radio station, 8HA, provided the air time - not through any altruist motives - but because they were worried that their licence would not be renewed of it didn’t provide some programming for the town's large Aboriginal audience. At the time, this very modest program was the only media service of any kind specifically designed for Aboriginal people, in their own languages, anywhere in Australia. More importantly, it was to lead to the establishment of the first Aboriginal media organisation in the county, CAAMA.

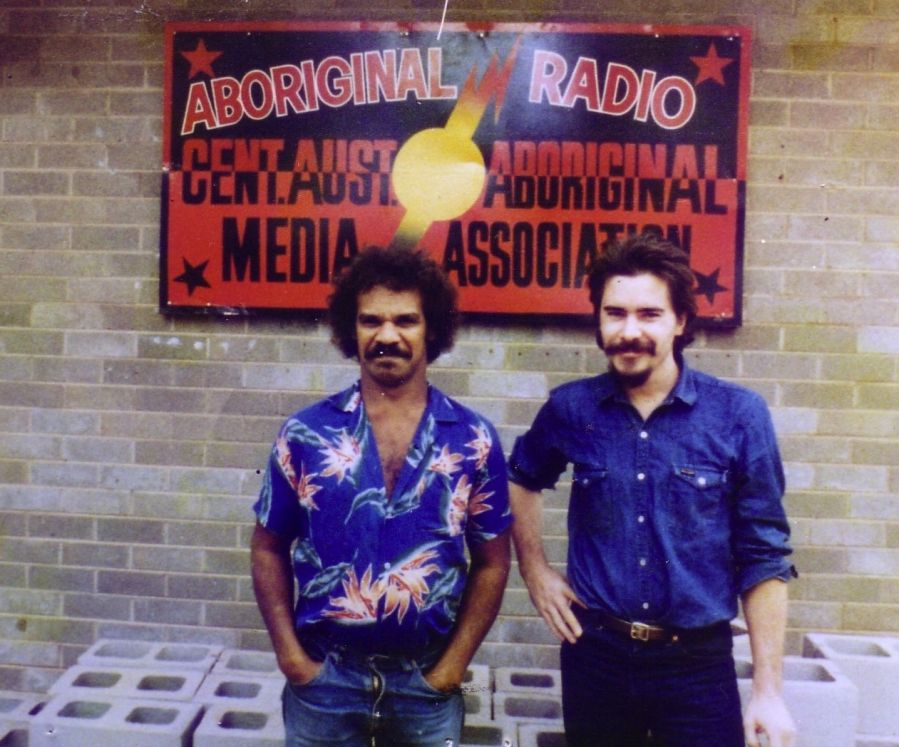

John Macumba & Philip Batty

I took up work on the Half Hour with John Macumba, an Aboriginal man from Oodnadatta in South Australia who had recently moved to Alice Springs with his family. Essentially, I produced and edited the Half Hour, while John presented it. The program contained a wide variety of material including information in the main Aboriginal languages Central Australia. Despite the poor broadcast time - 9.00pm on Sunday nights - the program developed a dedicated Aboriginal audience in Alice Springs and outlying districts.

From the outset of our collaboration, John Macumba and I had ambitions that went far beyond the Half Hour. We shared the same enthusiasm about the development of an Aboriginal organisation that would work towards the establishment of an Aboriginal owned radio station and other media services. We eventually managed to organise a community meeting of local Aboriginal people to discuss our proposals on the 27th February, 1980. As a result, a committee was formed to draw up a draft constitution for the new body. As planned, John became the Director of the new organisation, and I was appointed as Deputy Director. In May 1980, the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association was formally incorporated and we set about building the new organisation from scratch.

Because nothing like CAAMA had ever existed before, we had an advantage when it came to acquiring the support of government. It also involved the hard work of breaking through a number of barriers and forcing bureaucrats and politicians to establish policies, regulatory guidelines, funding facilities and a range of other enabling-actions that would allow for the establishment of an independent Aboriginal broadcasting service. In fact, the many precedents we set at this time would facilitate the formation of many more such services across Australia. Some of those precedents are as follows:

Early CAAMA Staff, Alice Springs, 1983. L- R: Bo Barney, Issac Yamma, Erica Glynn, Philip Batty, Dean 'smurf' Sultan, Rodney Gooch, Freda Glynn, Janet Hoare (front), Ronnie White, David Batty (obscured), Carol Kanatwarra, Ivan Dixon, Christine Palmer, Clive Scollay (obscured), Rachel Wellington

First. We convinced the Federal Australian Government to actually take the idea of Aboriginal media services seriously. To force this point, we went directly to Parliament House in Canberra and met with the Minister for Communications, Tony Staley (then a senior member of Cabinet) and Fred Chaney, the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs. Surprisingly, Staley was very supportive of our plans and within weeks, came to Alice Springs with Chaney to discuss the details of the Government's assistance. This rapidly led to material and regulatory support for CAAMA and critically, to the implementation of numerous administrative measures within Government to assist in the development of Aboriginal media services generally.

Second. We successfully persuaded the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) to help CAAMA put radio programs to air in Alice Springs and to develop programming for and about Aboriginal people on all their outlets across Australia. This was achieved through submissions we presented to the Committee of Review of the ABC (‘The Dix Committee’) when it was holding hearings in Alice Springs in June 1980 [14]. This was the only submission received by the committee concerned with Aboriginal interests. In fact, when we pointed out that the ABC was doing nothing about Aboriginal programming, an ABC executive later recalled that this gross omission hit him ‘like a ton of bricks’ [15]. The ABC immediately established a high-level task force to look at ways of incorporating an Aboriginal presence in all of its policy formulations, programming and employment arrangements. Today, the ABC runs numerous radio, television and other programming for and about Aboriginal people. It also employs Aboriginal staff, up to and including senior positions. All this began with CAAMA's submission to the Dix Committee, presented in Alice Springs forty one years ago.

Third. CAAMA was only one of a few Aboriginal organisation to raise concerns about the domestic satellite AUSSAT, and its possible impact on remote Aboriginal communities. Such concerns were taken up directly through meetings with politicians, bureaucrats and written submissions. These early interventions eventually led to CAAMA's successful bid for a licence to operate a communications channel on the satellite through its company, Imparja Television (see below).

Fourth, in the early months of 1980, we initiated a training program for Aboriginal people with the support of the federal department of education and training. These early efforts rapidly expanded as CAAMA grew and eventually evolved into a partnership with the Australian Film and Television School. Over the years, CAAMA trained a whole generation of young Indigenous people who went on to form the nucleus of today’s Indigenous media culture in Australia. The long list includes: Warwick Thornton and Rachel Perkins, now internationally acclaimed filmmakers as well as Erica Glynn, former manager of Screen Australia’s Indigenous Department and many more.

In May 1981, John Macumba decided to leave CAAMA. He had been offered a substantial managerial position he could not refuse in his home town, Oodnadatta. Despite my pleadings, he accepted the job and left Alice Springs. John's departure left me with a large problem. Up until this point, he and I had driven the development of CAAMA. Nonetheless, I was now left as the Director of the fledgling organisation without an Aboriginal partner. Although the CAAMA Committee had no qualms about a whitefella like me working as their CEO (other Aboriginal organisations had white CEOs, and still do), it was not, as far as I was concerned, a tenable arrangement. CAAMA had to have an Aboriginal Director and that Director turned out to be Freda Glynn.

Freda Glynn, CAAMA, Alice Springs, 1983

I had met Freda in Alice Springs socially prior to my involvement with CAAMA. She had also attended the first successful community meeting to form the organisations. Freda had begun to receive training with the ABC (following CAAMA's submission to the Dix Committee) and had helped with some of CAAMA's radio programming. Eventually, she was employed by the ABC to present an Aboriginal segment on its Alice Springs station, 8AL. Not long after John Macumba's departure, I asked Freda if she would replace him. Fortunately, she readily agreed to leave the ABC and take up the position of Co-Director of CAAMA in July 1981. The decade I spent working with Freda, growing CAAMA from a small community organisation to the owner of a satellite television service covering a third of the Australian continent, were without a doubt the most intensive years I have ever experienced.

The launch, in 1985, of the first Aboriginal radio service in Australia, 8KIN-FM, was only one of many activities we were engaged in during this extremely busy time. While developing the new station, we were also keenly focused on the forthcoming launch of AUSSAT. Indeed, CAAMA's engagement in this development was to have far reaching consequences.

When the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal (ABT) announced that it would hold public meetings across Australia to discuss the satellite, I felt that this would be a perfect opportunity for CAAMA to present its concerns and hopefully produced results similar to what had come out of the Committee of Review into the ABC.

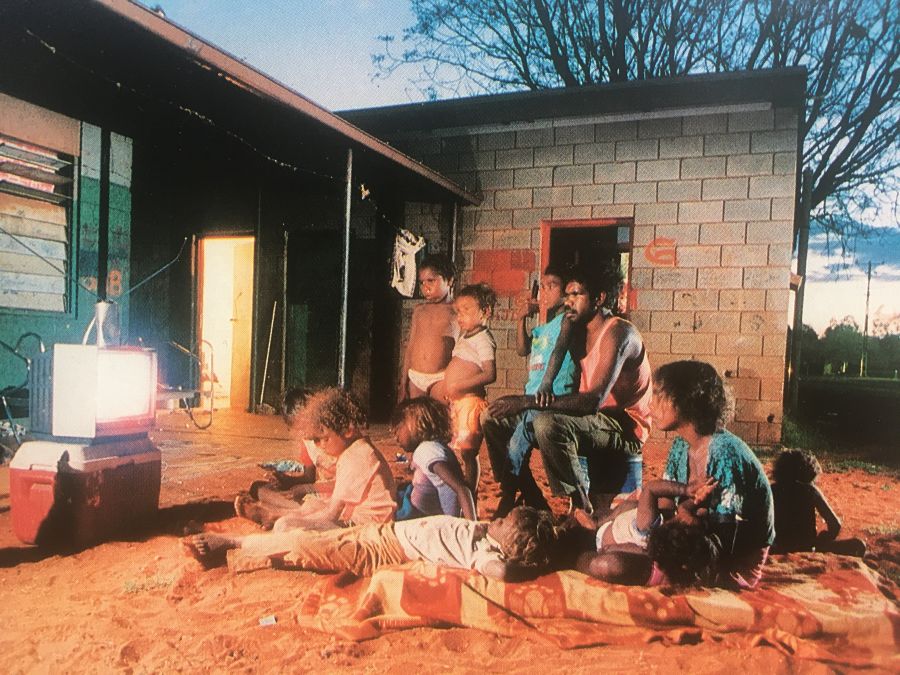

Family watching satellite television at Yuendumu, Central Australia, 1988 (© ?)

However, when I read the list of townships where these hearings were to be held, there was no mention of any Aboriginal communities, even though they made up a very substantial sector of the audience (AUSSAT was designed to deliver television services to remote regions and a few rural areas of Australia, not cities). As a result of this omission, I wrote to the ABT, on behalf of CAAMA, asking that at least one of the hearings should be held in a remote Aboriginal community. To my surprise, the ABT agreed and asked for suggestions. I proposed the community of Kintore, located some 600 kilometres west of Alice Springs. Not only was this the most remote Aboriginal community in Australia, the Aboriginal residents at Kintore had moved there from Papunya, so I knew many of them personally. This meeting would prove to be a pivotal moment in the history of Aboriginal media development in Australia.

Unlike the meeting on AUSSAT I had attended at Papunya six years before, the meeting at Kintore was well attended by representatives from several communities who were now very concerned about the possible impact of AUSSAT. Following CAAMA's lead, two Aboriginal media organisations had been established at the remote Central Australian communities of Ernabella (Ernabella Video and Television) and Yuendumu (Warlpiri Media Association), both of which sent delegations to Kintore. In fact, this was the first time in which Aboriginal people from remote communities had presented their views on AUSSAT to any government agency. The one common thread in these presentations was the need for local control of all satellite services entering communities. Ultimately, this was to lead to the implementation of the Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme (BRACS) which entailed the provision by government of local facilities that would allow Aboriginal communities to both manage incoming satellite feeds and produce their own material. For CAAMA, however, the battle with the satellite had just begun.

In 1984, we received news that the Federal Government had made a decision about who would have access to AUSSAT. It directed that licences to operate satellite TV services - and therefore, the controllers of access to the satellite - would only be granted to commercial television operators. Further, the ABT would decide who was to be awarded these licences, through a competitive process at public hearings. If anyone else wanted access to the satellite, they would have to negotiate with the successful commercial licensees. This meant that community-based bodies like CAAMA would have to beg these successful commercial operators for access with no guarantee of success. It seemed that CAAMA and other small potential satellite-users were locked out. Apart from writing a letter of complaint, there was, it seemed, nothing much we could do. The hope of CAAMA using the satellite was more or less shelved.

However, a few months after this news, I noticed, as expected, an advertisement in the local Alice Springs newspaper calling on interested commercial parties to submit licence applications to operate television services on AUSSAT. On the off-chance, I rang Brian Walsh, a Melbourne based communications consultant, and asked him whether CAAMA would have any chance of winning the licence if it applied. Brian was initially taken aback and thought not, but said he would think about it. A few days later he called back and suggested we might have a chance but it would be an extremely long shot. I then raised the matter with Freda and the CAAMA committee and they agreed that we should give it a try.

Of course, CAAMA had no interest in operating a commercial TV service, but if it did not submit a licence application it would have no guaranteed access to the satellite. If we won, we could indeed provide Aboriginal programming, but we would also have to broadcast predominantly commercial television material, yet CAAMA was established to counter such programming. In short, we would be forced to sup with the devil. In the end, we decided to apply for the licence as there was no alternative. Although we did not know it at the time, this decision would lead, through a complex, painful route, to the departure from CAAMA of Freda and myself.

Brian Walsh was hired to co-ordinate the licence bid and a substantial two-volume application was eventually delivered to the ABT in December, 1984. It contained proposals to broadcast a mix of commercial and community television programming, catering to both the Aboriginal audience, (then about out 35% of the total), and non-Aboriginal viewers. We created, on paper, a television company, ‘Imparja’ (meaning ‘track’ in the Arrernte language) to facilitate the bid. A few small problems remained however, CAAMA had no money to establish the service and of course, no track record of running a TV service, let alone operating satellite technology.

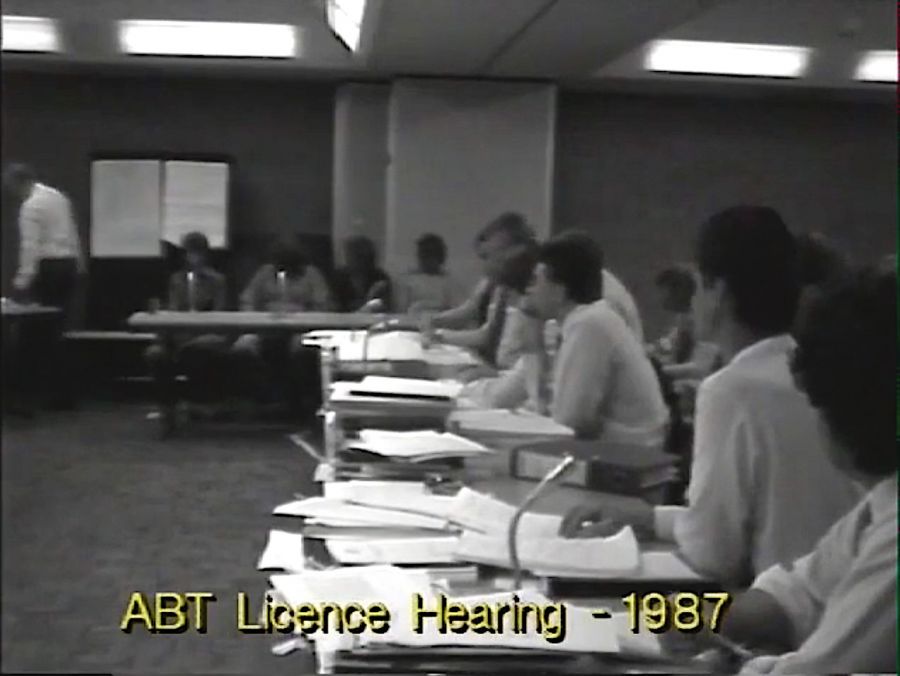

Still from Satellite Dreaming

The first hearing was held the 6th August, 1985 in Alice Springs. Just two contenders were up for the licence, CAAMA and the Darwin-based commercial TV station, Channel 8. We had twenty four Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal witnesses to support our case. It included the famous eye surgeon, Fred Hollows; the former head of the Federal Reserve Bank, H.C. 'Nugget' Coombs; the Minister for Education in the South Australian government, Lynn Arnold, (later, the Premier of that State); Rosemarie Kuptana, Head of the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation in Canada (via satellite) and many Aboriginal community representatives.

I held out little hope of winning the bid, in fact no one on our team did. We were therefore astonished when the ABT decided that neither CAAMA nor Channel 8 qualified for the licence and that another hearing would be called to decide the matter. In brief, CAAMA had ‘impressive’ Aboriginal and other non-commercial programming, but zero finance, while Channel 8 possessed the finance, but no Aboriginal programming and little else for local audiences. The next hearing was set down for the 17th March 1986, giving both parties six months to re-boot their applications. As the communications academic Eric Michaels suggested at the time, the ABT sent both applicants on a 'treasure hunt': 'CAAMA had to come back with six million dollars', while Chanel 8 had 'to find some Aboriginal content'.

The immense work involved in raising such a large sum of money - in just six months - and Channel 8's comic attempts to concoct 'Aboriginal content', are far too involved to elaborate here. Suffice to say that the relevant funding bodies promised to support CAAMA's application, if we won the licence.

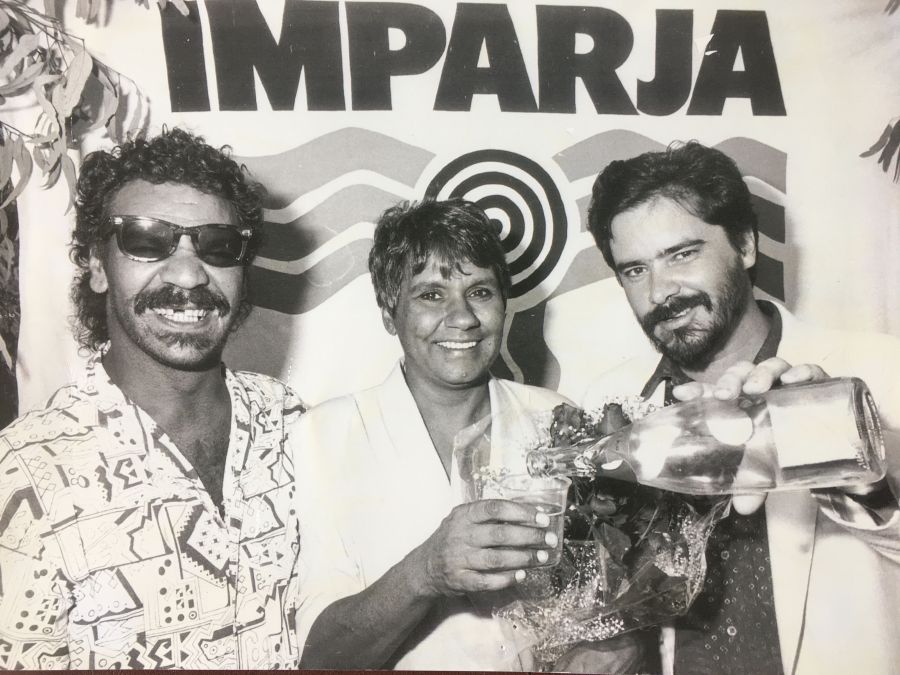

Following the second, tumultuous hearing, the ABT awarded the license to CAAMA in August, 1986, stating that ‘on balance’, CAAMA could provide a more ‘comprehensive’ service, especially in the area of Aboriginal programming. Once we had secured the license, the funding bodies made good on their promise to provide the required $6 million in funds. The decision produced a near hysterical response from the conservative Northern Territory Government. The Chief Minister, Ian Tuxworth, thundered, ‘this is a joke … giving a television signal that covers one-third of the Australian continent to a group … that is incapable, incompetent and unfinancial, is madness.' [16]

Work began on the establishment of Imparja TV soon after the ABT's announcement, and after a frantic twelve months, it went to air on the 15th January, 1988.

John Macumba, Freda Glynnn and Philip Batty at the launch of Imparja Television, Alice Springs, 1988. (© News Limited, Photographer: Caramel Sears)

During the first eighteen months, we lived up to our promise to broadcast a mix of Aboriginal programming and commercial fare. Using Imparja TV’s production studios, the CAAMA Video Unit produced two weekly programs: Urrpeye ('Messenger'), a current affairs show and Nganampa Anwernekenhe ('Ours'), presented in three Aboriginal languages, Arrernte, Pitjantjatjarra and Warlpiri, focusing on news and events in local Aboriginal communities. The Unit also produced a number of short segments on Aboriginal health, welfare services, legal aid, nutrition and child care that were broadcast throughout all Imparja programming. Further, the 8KIN network could now be heard right across the Northern and South Australia via Imparja’s satellite signal.

Unfortunately, by the end of 1990, serious internal arguments between senior managers had arisen within CAAMA and Imparja concerning the operations of Imparja. Briefly, as the service developed, it came under pressure to maximize its commercial income. This had an increasingly detrimental effect on the production of Aboriginal programming. For example, a greater priority was given to the production of local advertisements on equipment originally purchased through funds intended for the creation of Aboriginal programming. Freda and I insisted that Imparja should remain true to its original intentions of providing a mix of quality Aboriginal programming along with the commercial fare. In fact, this was the reason we had won the license. Our opponents within the organization claimed that as Imparja was licenced as a commercial television station, commercial considerations should take priority.

When the dispute was finally presented for resolution to members of the CAAMA Committee and the Imparja Board - all of whom were Aboriginal people - they failed to support us, leading to our eventual resignations. After we left, locally-made Aboriginal programming on Imparja virtually disappeared and what had been hailed as a ‘flagship of Aboriginal culture’ by the Premier of South Australia, became a B-grade commercial TV station, recycling second-hand network fare. Today, in 2001, with free-to-air television services becoming increasingly irrelevant in the digital age, it seems certain that Imparja will be sold off or more likely, closed down. The great things that so many people had expected to come out of Imparja never eventuated.

One can perhaps imagine my deep disappoint and indeed, despair at what had happened. I had spent some six years - along with many others - working assiduously to give Aboriginal people access and a measure of control over AUSSAT, and we had succeeded, way beyond what I had ever thought possible. However, most of the Aboriginal people into whose hands this licence was delivered - members of the Imparja Board - declined to use it for what we, and a host of our supporters - including members of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal - had envisioned. Essentially, they simply wanted to run Imparja as a commercial enterprise and the management of the station supported the decision whole-heartedly, indeed, they had advised the board as such. As a result, the station began beaming commercial television into remote Aboriginal communities with little if any Aboriginal content - something we had long railed against in all our public utterances.

The many arguments we had employed to gain the licence, including the need to head-off the effects of the satellite, now seemed like hollow rhetoric. We had indeed supped with the devil, and in the process, we had become the devil. I still find it difficult to understand why the all-Aboriginal board of Imparja allowed this to happen, particularly given the fact that the main players on the board were sophisticated representatives from the Northern Territory's Aboriginal land councils.

Setting aside the Imparja fiasco, the other areas in which I and others worked over the proceeding ten years, did successfully manage to build the foundations for the extensive Indigenous media sector we see today, and I remain proud of my participation in this exceptional development. As already noted, it is composed of a wide range of services at remote, regional and national levels, and on the face of it, seems to be flourishing. Yet, the uncomfortable question posed at the beginning still remains: why, despite this and many other efforts to improve the lot of Aboriginal people, does poverty and dysfunction remain a daily reality in large sections of Aboriginal Australia?

Trying to understand this conundrum is a complex business and not easily dealt with in a relatively short essay. However, I will offer some basic suggestions that might shed some light on this cloudy issue.

Children at a remote Aboriginal community in Central Australia, 2016.

First, if we lift the lid on 'Aboriginal Australia' we find multiple economic, social, political, linguistic and cultural differences at every level. In this world, dire poverty, disadvantage and failure exist alongside relative affluence, social advantage and success. This explains, to some extent, why we see both achievement and destitution in the one social body. At one end of this demographic mountain is an Aboriginal middle-class with wealth and political power more or less commensurate with other middle class Australians. According to researcher, Julie Lahn, in 2013 there are more than 14,000 individuals who could be described - and many of whom describe themselves - as belonging to an Aboriginal middle-class; making up around 13% of the total Indigenous population [17]. At the other end are people who live with generational impoverishment, chronic unemployment, ill health, excessive incarceration and ingrained welfare dependency who possess little if any political power. This Indigenous under-class resembles what Paulo Freire described as a 'culture of silence', where even an awareness of one's highly disadvantaged position remains, at best, opaque [18]. Tadhgh Purtill's book The Dystopia in the Desert [19] provides a confronting analysis of this problem. Between the two extremes of affluence and poverty are numerous variations in economic and social status.

In crude terms, the Aboriginal middle class generally inhabit urban environments and speak English only, while what we might call the Aboriginal lumpenproletariat are usually found in rural and remote communities and speak numerous Aboriginal languages and in some cases, very little English. Researchers, Markham and Biddle, have shown that while incomes for the urban Aboriginal middle class rose significantly between 2011 and 2016, incomes for those in remote areas actually fell. In highlighting this inequality, they argued that 'urgent policy action is required to ameliorate the growing … poverty among Indigenous people in very remote Australia.' [20].

While this wealth gap is enormous, and increasing, there are important exceptions. Few remote Aboriginal communities are without small, dominant Aboriginal families, with economic and political power akin to their middle class urban brethren. This was made abundantly clear in Russell Skelton's, award winning book, King Brown Country [21] on local power hierarchies operating at Papunya; something I personally witnessed during my time in that community. Conversely, poverty in city and regional Aboriginal communities is not entirely uncommon. In short, the gulf between the upper and lower echelons of 'Aboriginal Australia', regardless of their geographical location, is immense, and in my view, far greater than in any other single social group in the country.

It seems clear that the better-off sectors of Aboriginal Australia have, in general, been able to take advantage of and indeed, thrive in the many government-supported organisations and institutions where opportunities have been made available to them. This includes some 3000 registered Aboriginal organisations across Australia, numerous government agencies, health services, university departments, arts organisations and of course, Aboriginal media organisations including NITV, all of which are often held-up as successes. Conversely, the poverty stricken sections of the same community possess neither the education, nor the basic life-skills to effectively partake of such opportunities.

This is not a criticism of middle class Aboriginal people. They have the right, like all other Australians to acquire a level of affluence and well-being for themselves and their families. Nor should it be surprising that internal disparities exist within Aboriginal Australia; this is a common feature of all human societies. According to Oxfam Australia, 1% of the global population currently owns more than double that of 6.9 billion people [22]. Nonetheless, while the increasing problem of global economic inequality is subject to voluminous reports and policy initiatives, as it should be, the tremendous disparities in wealth and more problematically, in political power, inside Aboriginal Australia, are rarely addressed, nor are its effects.

The problem of inequality is only one of the possible answers to the question posed at the beginning of this essay: why does dire poverty continue to exit in Aboriginal Australia despite years of government investment? In my estimation, one of the other major issues that contribute to ongoing Aboriginal disadvantage is the problem of what can be broadly described as Aboriginal community governance. Here I am referring to the large network of Aboriginal organisations, as noted above, that currently administer and provide services to Aboriginal communities in Australia, encompassing most of the Aboriginal media bodies. These are the same organisations I first saw mushrooming in Central Australia in the 1970s.

Such bodies were certainly implemented with good intentions, but have become, in many cases, liabilities that tend to hinder, in my view, rather than help Aboriginal people. A number of these organisations, including some of the larger ones, have been in operation for over forty years yet have failed to improve the well-being of the poorest sections of the communities they were established to assist, thus perpetuating their poor living conditions.

One of the major problems with these organisations is the unfortunate fact that they are prone to chronic maladministration and corruption, which of course, has a devastating effect on the people they are obliged to serve. The government watchdog, Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations, receives, on average, some 800 complaints per year about the operation these bodies; a remarkable yet depressing figure given the relatively small number of functioning Aboriginal organisations [23]. Further, investigative television programs such as the ABCs Four Corners, have revealed alarming levels of fraud and mismanagement in a number of Aboriginal corporations across the country [24]. This is not, of course, to imply that Aboriginal people are inherently corrupt, but rather, it indicates how the system of governance created by government to provide services to Aboriginal people is not only flawed but, as a result of its poor design and lack of oversight, helps to facilitate the perpetuation of a poor Aboriginal underclass. At this point, it might be helpful to provide a brief history lesson about these bodies.

When the Whitlam Labor Government took power in 1972, it abolished the governmental system that had administered Aboriginal communities in the Territory for decades. To replace this system, it came up with the idea of creating Aboriginal 'community-controlled' organisations to provide the services it had abolished. These new bodies were incorporated under special legislation, funded by government and overseen by all-Aboriginal boards or committees. At the time, it was expected that non-Aboriginal people, or 'community advisors', would assist in the management of these organisations on an interim basis until Aboriginal people could run them themselves without non-Aboriginal or government involvement, and thus, 'manage their own affairs,' under the policy of 'self-determination'. As already noted, I and many other white activists took these policies to heart and worked with Aboriginal people to establish numerous Aboriginal organisations during the early period of this government project. However, the original aims of this project were never realized and on reflection, never could. Indeed, what actually evolved was far from what Labor could have ever envisioned.

Having worked, on and off, in association with Aboriginal communities for some forty years, I have never once encountered an Aboriginal organisation run entirely by Aboriginal people, as the polices of self-determination had proposed, and its few remaining adherents still insist they should. On the contrary, while these bodies generally have boards composed of Aboriginal people, their key managerial staff are often non-Aboriginal people who work in varying arrangements with Aboriginal 'co-managers', who in many instances, originate in the Aboriginal middle-class described above. In fact, it is not uncommon to find Aboriginal organisations managed entirely by non-Aboriginal people, including Aboriginal broadcasting services.

The Aboriginal radio station, Waringarri, in the Kimberly region of Western Australia, does not, according to its website, currently employ any Aboriginal people in its senior ranks. In fact, a non-Aboriginal presenter fills the station's prime-time breakfast spot. Further, it runs what it terms a 'Tourist Radio' service aimed at non-Aboriginal visitors to the area [25]. The case of Waringarri is, I think, particularly egregious. It clearly demonstrates the extent to which 'Aboriginal controlled' organisations can become increasingly detached from the people they are supposed to serve and the policies in which they originated. The Kimberley region in which Waringarri operates, is the same region in which Aboriginal youth suicide rates have reached epidemic proportions and are currently the highest in the country. While it would be foolish to attribute a direct causal relationship between these appalling statistics and Waringarri, it would not be unreasonable to think that an Aboriginal broadcasting services, operating across the Kimberly region for thirty years would have had at least some positive influence on its Aboriginal youth. What seems to have happened instead is an almost complete detachment between the people running Waringarri and its ostensible audience, including the region's Aboriginal youth.

In the case of commercial enterprises 'owned' by Aboriginal community interests, managerial arrangements can be so far distant from the people they were established to benefit, that they seem bizarre. Imparja is a case in point. Except for a brief period, it's management and the vast the majority of its staff have always been non-Aboriginal and as we have seen, its programming output has for the most part remained commercial, and all of its customers have been, of course, non-Aboriginal advertisers. Like many other 'Aboriginal enterprises' established to benefit Aboriginal people, the main beneficiaries of Imparja have been non-Aboriginal, despite the $6.0 million given to it to by government to create an 'icon of Aboriginal culture.' Another, perhaps even more bizarre example is the case of the Aboriginal 'owned' investment company, Centrecorp, based in Alice Springs.

Centrecorp was established by one of the largest Aboriginal organisations in the country, the Central Land Council, with the sole purpose of investing mining royalties (paid by mining corporations operating on Aboriginal lands) in private, non-Aboriginal companies. It is managed and operated exclusively by non-Aboriginal staff and overseen by a board composed of members drawn from the upper echelons of the local Aboriginal community, some of whom, incidentally, also served on the Imparja Board. Apart from investing in one of Alice Springs's largest liquor outlets, Centrecorp took a 50% stake in the local Toyota dealership. An incident recently took place at this dealership that for me sums up the disconnection between the upper and lower sectors of Aboriginal Australia and how the deep structural flaws in the Aboriginal organizational system not only works to consolidate this separation but helps perpetuate the poverty of those at the bottom.

"Youths damaged more than 50 new vehicles in Alice Springs in July 2017. (Supplied: NT Police)" - © ABC News.

In 2017 a small group of Aboriginal youths entered the Toyota dealership in the early hours of the morning and set about wrecking some fifty new vehicles [26]. Using an assortment of metal instruments and rocks, they systematically smashed the windows, headlights and panels of the parked cars. It seems certain that the youths - some as young as fourteen - had no idea that they were destroying vehicles owned 50% by an Aboriginal organisation set up to ostensibly benefit people like themselves. In fact, even if they knew, I doubt they would have acted any differently. The youths were from what are known as the 'town camps' of Alice Springs where crime, domestic violence, alcohol abuse and chronic dysfunction are endemic to daily life. It's more than likely that they would have never met the Aboriginal board members of Centrecorp, let alone considered them part of their world. Of course, they were eventually arrested and incarcerated in detention centers already overflowing with offenders like themselves.

Despite all of the above, I am not arguing that Aboriginal organisations, should be run exclusively by Aboriginal people as the original policies envisioned. Such an absurd demand was always driven by an ideological agenda, impossible to implement in any practical sense. Indeed, trying to create anything that is 'racially pure', be it an organisation or a nation, is not only impractical, but always leads, as history shows, to disaster. In short, the problem with these bodies is that they were developed and continue to exist in accordance with unworkable policy frameworks. The distortions and corrosive structural dynamics these frameworks produce within these organisations are too complex to go into here. Suffice it to say however that it has facilitated the kind of problems noted above: corrupt practices, mismanagement and most unfortunately - as we have seen with Imparja, Waringarri and Centrecorp - a sometimes complete disjunction between these bodies and the people they were meant to serve.

In this essay, I have pointed to some, but by no means all, of the possible reasons why there exist an almost unfathomable conundrum at the heart of Aboriginal Australia: why, with so much support and apparent success, is there so much dysfunction and despair. In exploring this puzzle, I have at times contradicted myself and presented highly critical arguments about organisations I once helped to establish and operate. Although I worked determinedly, like many others, to advance the 'Aboriginal policy revolution' of the 1970s, I now feel that it not only produced many unforeseen outcomes, it also helped facilitate the extreme inequalities we see within Aboriginal Australia today and created the kind of corrosive and largely ineffectual administrative system that still operates in so many Aboriginal communities. Nonetheless, while I was once a part of this system, that should not preclude me from offering a critical account of its failures. In fact, it seems to me that people who worked to establish this system are duty bound to reveal its shortcomings in order for something better to replace it. This unfortunately is rarely the case, despite increasing levels of Indigenous incarceration, suicide, poverty, domestic violence and all the other maladies, there are many defenders of the system and the policies that allows this appalling situation to continue. Indeed, they usually have a self-interested financial, reputational or ideological stake in its perpetuation.

I would like to conclude on a somewhat brighter note. When I began setting up CAAMA with John Macumba in the early months of 1980, neither of us knew, or could know, that it would spark the development of what is now, an extensive Indigenous media sector across Australia. This sector now contains a large group of talented Aboriginal filmmakers, broadcasters, script writers, directors, producers and other media workers who were entirely absent before CAAMA was established. While the current policy directions in Aboriginal Australia certainly need a radical overhaul, the very existence of this talent gives us some hope for the future.

All images © Philip Batty unless credited.

Footnotes

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2020, Productivity Commission, Canberra. See Figure 8.8 in main report.

Australian Law Reform Commission, Pathways to Justice—Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Final Report No 133 (2017) See Figure 3.1

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. Cat. no. FDV 2. Canberra: AIHW. See Figure 7.4

National Indigenous Australians Agency, Australian Government: https://www.niaa.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/land-and-housing

Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, 2017 Indigenous Expenditure Report. See Table 3.1

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021. Youth detention population in Australia 2020. Cat. no. JUV 135. Canberra: AIHW

Siewert, R. (2017). Ten years of intervention. Arena Magazine (Fitzroy, Vic), (148), 5–7.

Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle, 'Little Children are Sacred" - Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, Northern Territory Government, 2007.

Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle, 'Little Children are Sacred" - Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, Northern Territory Government, 2007. p. 5

Mary-Anne L Measey, Shu Quin Li, Robert Parker, Zhiquiay Wang (2006). Suicide in the Northern Territory, 1981-2002, Medical Journal of Australia, 185: 315-319

Northern Territory Land and Sea Action Plan, Northern Territory Government, 2017, p. 4

Report. Committee of Review of the ABC, May 1981, AGPS, 1981

Personal communication with John Newsome, Controller of ABC Radio Services.

Northern Territory Legislative Assembly, Hansard 1986: 609 - 611.

Lahn J. (2013) Aboriginal Professionals: Work, Class and Culture. Working Paper No. 89/2013, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Continuum

Purtill T. (2017) The Dystopia in the Desert, Australian Scholarly Publishing

Markham F. & Biddle N. (2016) Income, Poverty and Inequality, Census Paper No.2, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra.

Skelton R. (2010) King Brown Country: The Betrayal of Papunya, Allan & Unwin.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2020, Productivity Commission, Canberra. See Figure 8.8 in main report.

Australian Law Reform Commission, Pathways to Justice—Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Final Report No 133 (2017) See Figure 3.1

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. Cat. no. FDV 2. Canberra: AIHW. See Figure 7.4

National Indigenous Australians Agency, Australian Government: https://www.niaa.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/land-and-housing

Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, 2017 Indigenous Expenditure Report. See Table 3.1

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021. Youth detention population in Australia 2020. Cat. no. JUV 135. Canberra: AIHW

Siewert, R. (2017). Ten years of intervention. Arena Magazine (Fitzroy, Vic), (148), 5–7.

Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle, 'Little Children are Sacred" - Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, Northern Territory Government, 2007.

Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle, 'Little Children are Sacred" - Report of the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, Northern Territory Government, 2007. p. 5

Mary-Anne L Measey, Shu Quin Li, Robert Parker, Zhiquiay Wang (2006). Suicide in the Northern Territory, 1981-2002, Medical Journal of Australia, 185: 315-319

Northern Territory Land and Sea Action Plan, Northern Territory Government, 2017, p. 4

Report. Committee of Review of the ABC, May 1981, AGPS, 1981

Personal communication with John Newsome, Controller of ABC Radio Services.

Northern Territory Legislative Assembly, Hansard 1986: 609 - 611.

Lahn J. (2013) Aboriginal Professionals: Work, Class and Culture. Working Paper No. 89/2013, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Continuum

Purtill T. (2017) The Dystopia in the Desert, Australian Scholarly Publishing

Markham F. & Biddle N. (2016) Income, Poverty and Inequality, Census Paper No.2, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra.

Skelton R. (2010) King Brown Country: The Betrayal of Papunya, Allan & Unwin.