Clive Scollay

“Isn’t it about time they told their own stories?”

I grew up in Canberra. Which was an extraordinary frontier town at the time when I grew up. My father migrated there from after being a prisoner of war in Germany for five years and … he was an architect and an artist.

My father had said to me when I was growing up - he'd migrated to Australia and I was one and a half when I moved there. He said “Son, we're never going to be comfortable in this country until we understand the people that have been here before us. And adopt into our culture the things that are right for us and can progress that culture and, you know maybe you should be finding out about it and seeing what you can do to assist”. I never took that seriously…

I always spent my… life as a singer or being involved in the arts in my one way or another or student politics.

I did a degree in politics and law and then I did a design graduate design diploma in which I did some film studies - 16 mm - and made a film that won an a AFI award in Australia with Ben Lewin who later went on to make some quite well-known films.

I had always thought of myself as being …in the media as a commentator on this side of the camera, because quite a few of my mates did become that. And instead I ended helping to set up the Australian Film, Radio and Television School which put me in touch with a whole swag of future policies for the development of cinema in Australia.

I was drafted to go off to Vietnam but I had had a car accident when I was 17 so - cutting a long story short - I ended up not having to go to Vietnam and instead joined the public service. I spent three years working as executive officer to set up the Australian Film, Radio and Television School. I learned to do 16 millimetre production, in the great old days of celluloid and.. but at the same time I started to read about the Challenge for Change programme in Canada, run by George Stoney, which was using video as a community development tool, mostly with Inuits and North American Indians, and I was…I thought that I could find a way to apply that - and once Jerzy Toeplitz had been appointed the director of that school I left having got hold of the film rights to D.H. Lawrence's Kangaroo…

…and I went to America, Los Angeles and New York and then to London to sell the D.H. Lawrence story. After I'd been to Hollywood and hadn't had a lot of success, and still on my way to New York, I took a side trip to San Francisco, staying with some friends - a new stream opened which was closer to the …the Challenge for Change stream. I ran into a bunch of guys – the Videofreex - run by led by a guy named Michael Shamberg - they were going to the Democratic and Republican conventions to use video as a, as a confrontational tool in the way but also a new production tool. And friends of mine were friends of theirs so I ended up going with them to, after Miami Beach and worked with them on the floor of the convention centre using video. And we… were part of the whole hippy zippy yippy fraternity down in Flamingo Park later on, who were there to support McGovern who was running against Nixon. And there were a lot of Australians tied up in that business but I learned a lot about… video as a production tool. Then I drove back down to Miami Beach for the Nixon re-election with a bunch of Vietnam Vets Against the War. So, it was a pretty politically charged environment which I was very much a part of. And we once again we were part of the Flamingo Park crowd who were taking on Nixon and the anti-, who were part of the anti-war movement.

I then travelled up to New York and went and met, and stayed in Greenwich Village and met George Stoney, and spent quite a lot of time with him talking about the underpinnings of the Challenge for Change programme and why it worked and what didn't work and why video was the right tool to use. George Stoney was awesome - I really enjoyed talking to him.

And from there I flew to London. By then I was starting to run out of money for getting my production of D.H. Lawrence up but I had learned a whole lot of new skills along the way with video and I felt more at home in that video world that I certainly did in the offices of the production companies of Hollywood… and I was walking down the Mall one day to the, is it the ICA? The Institute of Contemporary Art? There was a placard outside there saying there was a big discussion about the future of video. So, I thought I know a bit about that, I'll call in, and I found myself sitting in the audience you know, it was some kind of an open forum about discussing the future of video. And I kept found myself continually getting up and down and saying ‘Well I don't think it's quite going to be like that. I think it's more like this and you know I've just come from America and this is what they're doing over there and I think it'll probably be, you know, go in this direction”. And at the end of that forum ED Berman walked over to me and said "Would you like a job?" and I said "What do you mean?" He said “well we've just commissioned a Mercedes Van - a Big Red Media Van - and we need a Captain Video to run it. You want to do that? Apply what you've learned in America?” And I said: "Well, I wasn't exactly looking for a job but sure, I'd like to do that" And so I became a member of InterAction.

So, there were some fairly politically astute people in InterAction, and I recruited a few others who had come from various political backgrounds, and we were a team of five or six, travelling. We …began our work commissioning the van I suppose in the East End, in Docklands. We ran the Docklands… we were working with the Docklands campaign and we were … their back-up if you like. We introduced video into situations that gave them an opportunity to interview councillors and people living in housing, you know, a lot of walk-up, two storey walk-ups and very, very old established families, working class, you know: a friend of mine described it as the last victims of the British Empire all lived in the East End. And I felt quite at home you know because they speak a language close to mine.

One of the things that I was conscious of while I was working all over the place in the East End - I used to run into lots of people in the East End who used to say "Mate, what you should be doing with all the people here is encouraging them to migrate to Australia cos there's no future for them” - these people in the East End that were being shifted willy-nilly against their will. “Tell them to move to Australia, they might have a future". And I thought about what that really meant, and I also thought about…along the way started to get people asking me questions about Aboriginal culture. And I didn't feel that I could answer those questions about the country I live in - I had had actually probably more experience than a lot of people with Aboriginal people because my father who had been an arch…, was an architect and artist had worked with the Aboriginal community at, on the south coast. But that is very much a New South Wales culture, it's been damaged by the whitefellas for some time. Whereas I wanted to try and understand the essence of the culture.

While I was here, I was thinking you know, here I am working with the last victims of the British Empire in the East End, as my mate said. And working on you know the role of change… in British society at that particular time and getting a big snapshot of it right round the country. Maybe I should be thinking about how what I'm doing here can apply in Australia. So, I went back and I, you know, tinkering around the edges of the video movement and…

…there was a video movement that had started in Australia with the video centres in quite a few places in Sydney and places where there were fixed video centres where video was being used as a community tool. In a location like Marrickville or… which is an inner Sydney City suburb. To do a bit like what we had been doing. So, I threw my lot in with a few people that were doing that stuff and helped out a bit in some production work…I ran into an old friend from my days at uni who had a radio program… who was doing what I always wanted to do - was to be in the media. He had his own radio show and he was blowing the whistle on asbestosis, on asbestos… And I ran into him in William Street in Sydney and [he] said I've got a studio over here come over and I'll do an interview with you because whatever you been doing in England it sounds really interesting. So, I went over and we had a chat, half-hour talk, and I talked about what we'd been doing in England.

And at the end of the interview all these telephones lit up on the desk, you know these incoming calls, and I got about five offers of work right there. You know, I hadn't, I'd only come back and I'd only been there for a matter of weeks…

…one of those calls came from Darwin and it just - this is in March, early March when Cyclone Tracy had happened in December just before that. So, they were looking, there was no communications system in the city of Darwin. Television, radio and everything had been blown away and it and many of the occupants of Darwin, all the women and children had been evacuated.

And so, this guy who was running the Darwin disaster welfare council for NT Council of Social Services, was really interested in setting up an internal communications system where people could talk to each other. The Department of Social Services had devised this system where all the men that were left behind in the city of Darwin after the disaster could go into a department of social services office and record, or get hold of a video camera and a crew, go out to the house that they were rebuilding, record it what their work was and take it back to the DSS and it would be distributed down to wherever their wife and children had been sent. Who could in turn go into a DSS office in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Adelaide and watch the videos…So I helped with that system but I also helped in a more informal system of communication internally in Darwin with families that were still there who really needed a bit of spirit lifting and a bit of … you know, entertainment. And so we used to bootleg, or I'd go to Sydney and places like that and bootleg concerts on video… not Cat Stevens, Donovan in Darwin and nearly got bashed up by his manager because I was sitting there with the camera hidden in the audience and recording it… I did J.J. Cale and I did, illegally, all of them just, you know, with a video camera in my lap…I’d get a seat near the front and have kept the portapak under the bench, had to change the reels. A whole gang of us were doing that. And then I'd take ‘em back up to Darwin and show them. We set up … a playback system in the park in central Darwin so people could come and have an evening's entertainment and watch the latest stuff from J.J. Cale or whatever…So that was about a little bit about a town rebuilding itself or a city rebuilding itself and in the process of that I had … an editing suite right next door to the Aboriginal Cultural Foundation, whose job it was to keep … We had a board of elders across northern Australia from the Kimberleys to Arnhem Land and into north Queensland to keep traditional Aboriginal culture strong….

… over a period of time I build a relationship with them and did some quite ground-breaking work with them using video to support their cultural endeavours… did some very big festivals as a form of cultural expression and I helped to film those. I had met up as I said in Milton Keynes with Penny Tweedie who was, became my partner and the mother of my son Ben, and she and I had gone to Australia together. And she and I lived in Darwin and we went, she was photographing and I was doing videos and we ended up as creative arts fellows at the Australian National University… I was commissioned by the Aboriginal arts board to make a film about Aboriginal video about Aboriginal, well a film ‘cos they used Super 8, and video about Aboriginal bark painters and we did a story for National Geographic magazine, the American one, and we did, Penny did a book, several books so our output was quite strong. And we did spent quite a lot of time working with Aboriginal, giving Aboriginal people the opportunity to produce their own stuff - either in Darwin or out in Arnhem Land - and we lived, we had a studio in Canberra from 1978 and '79 and, but worked in Arnhem Land and lived extensively in Arnhem Land working on productions and got to know quite a few people lived in, living on outstations, total traditional culture.

In 1979 we organised the first exhibition of bark painting ever in an Australian gallery at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Ironically Nick Waterlow, who had been the arts officer in Milton Keynes had become the director of the Biennale in Sydney and so …we had talked a bit over a period of time and Nick had had a lot of demand to get Aboriginal art into the Biennale that year. It was called European dialogue. And there were a lot of European artists coming to Australia who all wanted to engage with Aboriginal art. So Nick organised for us to bring down these artists and some huge bark paintings, and we also produced a film which was shown, so the artists felt comfortable when they came down from Arnhem Land they would sit in this theatre as this film was shown taking them back to their country. They feel comfortable enough to enter into a dialogue with people. So that was all part of a package.

But in that year too there was a huge conference at the… AIATSIS (the Australian Indigenous Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies) in Canberra. They had an ethnographic filmmakers conference - a group of you know, all the best filmmakers from all over the world. It was an international conference, and Penny and I and some of our Aboriginal friends from Arnhem Land and a couple of other filmmakers went deliberately to be provocative… Here were all these …big, big shot fantastic filmmakers and we were taking our position from having been in Arnhem Land saying "Isn't it time that you were putting your cameras in the hands of the people you're filming? You know you are wonderful filmmakers and you're, you're opening the world to stories from Africa and India and you know, Aboriginal Australia and the Arctic and Antarctic and whatever, but you're telling the stories about people, rather than putting the cameras in their hands. Isn't it time that they told their own stories and in their own way?"

…nearly a year later I was, had just finished, Penny had gone back to England and we'd sort of split up - she moved back here with Ben - and I was thinking I really wanted to go find out about the desert, immerse myself in the desert, and I just finished the text for the last final edit for the National Geographic story and I got a phone call. And this woman rings me up and says "Hello I'm Petronella Wayfair and I'm at the Institute of Aboriginal Development in Alice Springs and I'm wondering if you'd like to put the words that you were speaking at the ethnographic filmmakers conference into action? There are some Aboriginal people here who want to start a radio station. Would you like to come and be their consultant? They've got enough money to employ you for a couple of months…” And so I was on the next plane…

…CAAMA was established - the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. I was their first trainer, their first consultant, their first… We bought the first lot of equipment and one of the things that I did first of all was to take the CAAMA committee, the future committee, on a road trip to see television stations and radio stations around Australia. And we had lined up in Sydney, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide for people to see commercial stations and ABC and community stations, and there was no other Aboriginal media in Australia, this was the first…

The man who had the vision for this radio station was Johnny Macumba, supported by Philip Batty. Macumba was an extremely intelligent guy, an Aboriginal man, but he had a disability, he had M.S. very badly, so when he walked he looked like a drunk man. But once he was in …place he could, he was a very clever negotiator and a very clever articulate speaker, but you know getting him there was a bit of a problem, and I thought a lot about how what we how we could get him into situations without everyone being a bit embarrassed because in an instant response from most people would be “Oh look, there's a drunken Aboriginal” - I didn't want that to be happening. So, I contacted each of the places we were going to asked them if they had a boardroom: could we meet, go to the board room - our little group of six or five or six people, seven people or something - go and sit in a boardroom and then maybe the production staff could come and talk to them? So this was the future board of CAAMA, who had experience all the way round Australia of sitting in the boardroom and the production staff coming to them, asking them questions about what their job was and what their role was and so on, and then being taken by those production staff, to show them the facilities - so they were right from the very beginning in control, if you like. It even worked that way in Parliament House in Canberra. We went to meet the Minister for Communications - Tony Staley - and we… got a committee room in Parliament House and all the politicians that wanted to come and see us, came and saw us. So we were there sitting in control, and they came and saw us, and Tony Staley actually offered the delegation the premises, the old Telstra premises in Alice Springs in Gap Road which became the studios and headquarters for CAAMA for some time.

…we had a small grant from the Films Commission which, to buy some equipment. So, we, we bought a couple of roving recording microphones and recording tapes and a mixing desk. And it was just amazing - the name of the mixing desk that we bought in Melbourne was The Alice. Fancy there being a mixing desk called The Alice to go to Alice…

… a friend of mine from DAA, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Ronnie Little, contacted me and said "Oh look, Eartha Kitt is going to be in Alice Springs. Would, and it would be fantastic if you could document her visit. Would you mind filming it" And I said “Sure, but don't pay me, pay CAAMA…” And so, we went out to a few communities and things and …I discovered towards the end of the trip that Eartha Kitt was this huge role model for a lot of the black women, Aboriginal women, because there were no other role models of highly successful black face, a black woman. And here she was in their presence, so one of the members of the board was Barbie Shure who was a really articulate, very smart woman who had been in the health service, but to her Eartha Kitt was a goddess. And so, I said “Well, this is your opportunity, Barbie, to test your skills as an interviewer. You do the interview with Eartha Kitt”. And Barbie was then absolutely petrified but she did it really brilliantly. So, one of the first ever interviews done on the new equipment …Eartha Kitt was one of the first people and they still talk about how she was the first person to give them some money, some commercial money.

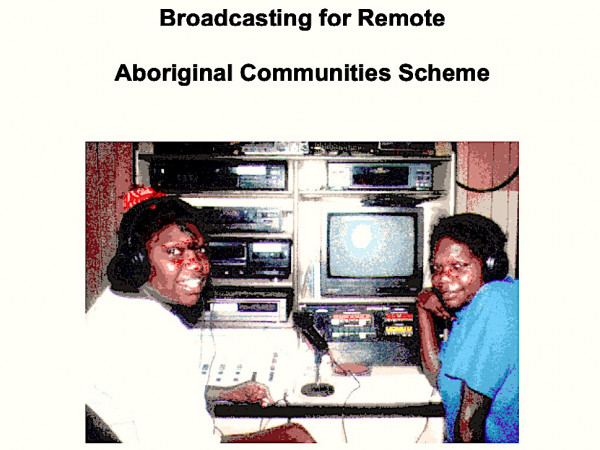

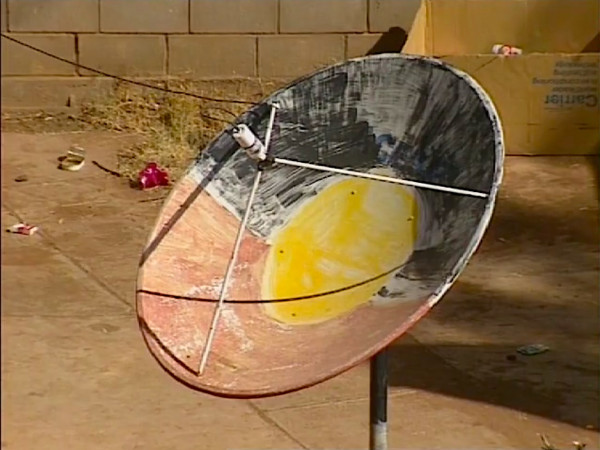

in 1984 I went back to CAAMA to help the bid for the satellite which led to Imparja Television, and also to set up the BRACS system which was an attempt on the Government's behalf to try and kill off Ernabella Video and TV. There were two um production units that were quite an annoyance to the government because they were self-funding and they were, you know, seemed to be a threat of revolution. There was a production unit in a community, a Pitjantjatjara community called Ernabella - that was EVTV - and another place called Yuendumu and they had Warlpiri Media in - both of those organisations were independent broadcasters. So they thought they could bury those two by creating a BRACS system, so they funded what later became quite a potent production tool, because the BRACS I think went into 22 communities around Australia and I put together the training manual and did the training of the initial people that worked in those communities - community members who are running their own satellite television…

…There have been a few vestige BRACS stations have continued to exist in a few remote communities. They were, they lasted a surprisingly long time on pretty cheap equipment. They were never given adequate equipment or adequate facilities, so it was bound, they were bound to fail after a certain period of time and they've never been replaced or renewed but they have a limited radius FM broadcasting capacity. And I think you know there was a time maybe for 10 years where that BRACS system had real potency in those communities - it did, a lot of people were telling their own stories and dancing their own dances and showing them on local media and not watching mainstream television. But I think those days are fairly well gone. But it was a good, it was a good attempt.

…Jim Downing was the head of the Institute of Aboriginal Development and a pastor in the Uniting Church who had fought hard for Aboriginal land rights, and he was leaving Central Australia to move to Darwin. He asked me to go with him to film his last journey through all the Pitjantjatjara communities. And I thought if media is ever going to be useful in a remote context it would be a good idea to understand that remote contexts - not just in Alice Springs. So I went with Jim and made a film called [?] which was about his, him saying goodbye to all these traditional elders, and while I was on that trip I got to town, a place called Amata, where there was a position as a community advisor available and I said to Jim “I wouldn't mind trying that”. And he said you know, “It'll make you or break you, it's a pretty tough town”. So I decided that I would take on that job and I did. And ultimately that leads to where I am now because Amata was a place with 10,000 head of cattle and four or five hundred Aboriginal people and an arts centre. And I got a mate of mine - Peter Yates - to come and run the arts centre. And we went in 1981 with a tent over to the foot of the climb at Uluru, with a group of 20 artists or so and sat there for a week where they made their art. So, we'd heard that there was going to be this thing called tourism and we wanted to find out whether we would be, could be part of it. And so we sat there, and the artists made their artifacts and wood carving and then did traditional dance at night. And then Peter Yates and his wife Pat Tarango worked for the next few years from Amata, regularly visiting Uluru and created another more formal tent and eventually in 1984 they were given the old hotel which had been a visitor's centre in in the old Ayers Rock campground when Yulara village opened and that's where we are now, as Maruku. So I'm now the general manager of Maruku living in that, working out of that warehouse in Mutitjulu community at the foot of Uluru.

Aboriginal affairs in the meantime has been… I've been living in communities and working either in the media for much of the last 30 years and I think one of the things that's happened is that there is a fast pace of change being delivered by television and now by the mobile phone and mobile media, that's having quite serious impact on the next generation, the younger generation to pay more attention to which way round their basketball caps should be than listening to their grandfathers with traditional culture. That's not to say that the traditional culture is not still strong in places, and in the Pitjantjatjara lands it's particularly strong, but it's under attack from, ironically from media that is delivering the alternative, you know the mainstream American lifestyle that the whole world is taking on. In the mean-time also there's been of course the Intervention - it was launched in the place where we live, in Mutitjulu. It was launched there with a lot of lies and some media manipulation… ironically it was pretty much launched by a media programme called Lateline…

…you know, in Mutitjulu you know, it's essentially created in that community, it's created a group of men who feel embittered and put upon and blamed for something that was not happening and therefore it's dis-empowered people…. The whole intervention has created a lot of opportunities for bureaucrats and white Toyotas driven by bureaucrats and you know more government control than was intended. It's never been a bottom up process…

But the intervention has certainly not, I think, really contributed to Aboriginal authority or decision making.

…when I first started, we thought video was completely unique and a great production tool. This is everything. This is the telephone. This is the entire world. This is a production tool. This is everything in one. And I think understanding how to use that and social media nowadays is probably where things are headed. The effective use of social media and there are you know, I think there are people around that are working hard in that area.