Warwick Thornton

“We have a very specific way of looking at the world…”

Memories of Satellite Dreaming. Yeah. Lots of incredible memories. It was interesting you know working at CAAMA, you know you spent a lot of time in the bush. You … spend a lot of time in sort of very specific situations and to look …and you are so busy working at CAAMA and doing your own thing, or you know Nganampas, or you know whatever you were shooting, that you never really sort of stood back and looked at the forest in a sense. So it kind of became an… incredible eye opening. I was very young when I shot Satellite Dreaming and you know probably one of the biggest, you know it was the biggest thing I'd done at that time. And thankfully you know you guys gave me an opportunity to shoot. But …you were in the forest, and you're always looking at specifically what you were doing and what you were shooting and the jobs that you were working on - specifically Nganampa or CSAs - community service announcements - and that sort of stuff; and then suddenly going and doing Satellite Dreaming, and then standing right back and seeing the whole forest of what was happening in Australia at that time - whether it was ABC or SBS or it was PY media, or you know what Francis’ mob were doing at Yuendumu - that was just was an incredible eye opener - about, you know, language maintenance and you know, cultural storytelling in a sense…it became - you kind of felt like that you were you're a part of a much bigger machine after we shot that film - and an incredibly integral, important part of it – it made me feel really proud about what I was doing because you know there was, there was some acknowledgement of what CAAMA was doing, obviously, but as you know as that tiny little cog in CAAMA, which was part of a much bigger machine which was indigenous television and film making through Australia - it kind of it became a real eye opener.

It did become very apparent what was happening in the, in the sort of remoter communities and that sort of stuff, about what they were doing with their language and their stories in a sense. And, and you know it wasn't, you know - because I'd come from a very, very sort of empowering thing where you know, you shot stuff and it went on ABC or SBS, and that was kind of you know very important in a sense. But then you realized that what was more important was what was happening in those communities with those, with these much smaller productions. They were just basically sitting down with old men and old women and they were telling stories - these stories were never meant to go to cinemas or to be broadcast on TV. They were meant there, as to become a vault of …knowledge in a sense, and they were there to be kept so that people you know, later down the track when those old people had finished up, had access to…you know, the knowledge - and that, you realized, is much more important and more empowering than - I don't know - getting a presale to ABC.

We have a very specific way of looking at the world, and we are incredibly diverse bunch of people as well, you know - we have so many languages and so many different kinds of cultures inbuilt into that kind of one thing that is Australia. And so, we all have different perspectives. We all have different perspectives because of our upbringing as well, whether we're an urban blackfella or a desert blackfella or you know, or saltwater or fresh water - we have very different ideas. But it does simmer down to that sort of idea of cultural maintenance, and it does simmer down to that idea that we have a respect for our… people and our culture, and when we make films we have to have to look at that, and question ourselves about what are we saying about ourselves and who are we. And I think that can that can all boil down to you know, the blood that runs through us which is blackfella blood, and how we control it and how we nurture it, in a sense. The storyteller - being a blackfella I think we have a very unique perspective on storytelling. You know, we might use the same format and the same kind of composition and the same editing styles, but it's sort of, it boils down to something deeper than that, which I think comes from maintenance of who we are and where we come from…

That same thing about whether you…grew up in a very remote community, or you grew up in a…city, and you've had, you've got very different sort of connections to cinema or television in a sense - and that does dictate to you how you make a film, or how you compose or how you…But, there's the more distilled thought of it, is that sort of connection to country and community and how you show it, and how you show your culture, that this is more what I think it's about…

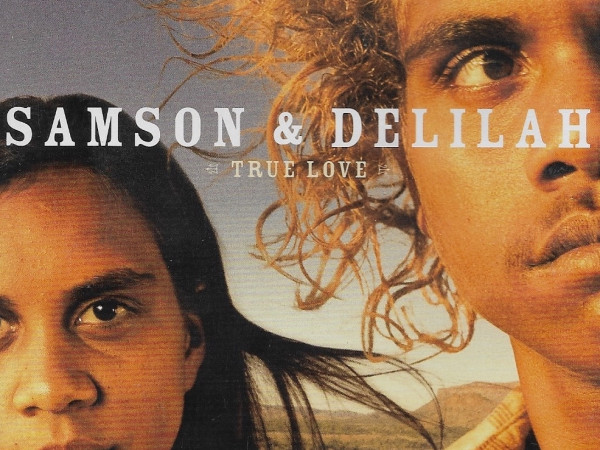

Like the ending of Samson and Delilah - you know what I mean, having that … It was so important for me as an Aboriginal person, that I was showing these stories about my people and our kids. But I needed a positive outlook at the end. I needed to give a tiny amount of light at the end of the tunnel for those children and for my people, in a sense. You know, I didn't want a dead-end street. I didn't want the whole plane to come down, you know, burn and crash. You know what I mean, all that kind of stuff. I wanted there to be light at the end of the tunnel and almost like a small glimmer of hope. And that came from inside me as an Aboriginal person…

I wanted to give my people who watch the film a happy ending, so that they can they can step, step away from the film and say ‘There is something for all of us’, in a sense…

We do have a connection to land - all Indigenous people do - that's far beyond a lease or a monetary idea or some kind of, [car horn: hello!] some kind of legal thing – it’s beyond that. We have this connection to land …as it being a spirit. It's sort of controlling us in a sense as well. And you know for them, and with that comes strength in a sense: if you think that way, when you walk through country it makes you stronger and it heals you. So, for them to be in the community that's really dysfunctional, you know what I mean, it's dilapidated, it's a bit of a warzone, it's incredibly neglected; and then they hit the tap, you know, hit town - where it's actually worse because you know, people just turn a complete blind eye to the tragedy around them - and fall into a, you know, sort of almost out of the frying pan into the fire; and then being able to go back to country. And then to be able to sort of heal yourself in a sense you know - just that little laugh that Samson does at the end, that's the laugh he uses right at the beginning of the film. So you see, hear him laugh again, and you feel, hopefully you feel that there's sort of a strength that's coming from the country, and a safety that's coming from the country, and a glimmer of hope and a light at the end of the tunnel, purely because of where they are in a sense, yeah.

You know, it is very expensive to live in the desert. And you know, that the state government and the federal government it's all, you know they've decided that these things are too expensive so they're shutting them all down, and they're just not financing… you know, they're not actually investing in these places, that are actually incredibly empowering to Aboriginal people and they make Aboriginal people stronger. You know, when you're on your homelands and you've got country and you've got, you've got a house or a shed, or … even you know that kind of access to it …it makes you better. You know, it heals … sicknesses, it heals sicknesses in people's heads - by being on country and being where their ancestors have been since the sun rose for the first, very first time, you know: being there makes you feel stronger. And suddenly it's like ‘Oh they're too expensive to run!’ - and so you know, how expensive it is to run these health systems in Alice Springs where actually you know, that country is going to heal people a lot stronger, you know: it's sort of …it's an interesting dynamic. Anyway, they kind of, you know with Samson and Delilah that was kind of part of the thing, because that all started about the same time I was writing Samson and Delilah, and I wanted to show that …these places for Aboriginal people, they are hospitals and they do heal, heal you know, your outstation is…. When you have country like that there, and you have access to it…just completely makes you a stronger human being.

You know, I wanted to make a teenage love story, but an Aboriginal teenage love story not a, you know an L.A. Hollywood love story which is, you know, it's written by 45 year old males and females who you know, have this sort of ‘wax lyrical’ knowledge of, you know: you have a paragraph that's all about love and then you give it to a 13, 12 year old girl. And so, like this is just so wrong. When I was 12 and 13 I couldn't explain what the hell was going on in my body about the girl I've fallen in love with or whatever…So, it was much more truthful to me. And you know … and it connected as well as the you know…these kids don't have a say, they don't have a voice. So I decided not to give them one in a sense, you know. And being so petrifiedly shy about love …well you know, they don't have that monologue that you see in Hollywood, that it seems children today have. So, it all connected to the way I grew up, and how I couldn't speak to girls …and the truth of the matter that the kids are actually you know, voiceless.

I think the film went down incredibly well in Alice. You know, we had a free screening for the whole town. And we brought community, you know we brought buses in from all the communities, to bring us many people from, you know outlying communities, not really remote communities but maybe what….And everybody seemed to love it. And you know, people you know, people were empowered by the film. I …you know, I'm…there is…there will be people who don't like Samson and Delilah - the film - because of the tragedy or the airing of the dirty laundry, in a sense. And it's understandable, it's a heart wrenching film to watch. You know, I don't watch it anymore, it's you know, it's just it's too painful. But …you know, I think I think most people really liked it. You know … there was questions asked about the … community that is Alice Springs, and what are we doing for these kids, you know, because the reality of the fact, those kids are here… they’re here today: Samson and Delilah are still wandering the streets of Alice Springs. And you know, people, people ask the question ‘Was there anything we can do?’ Which was good, it became more, it became more about the people asking the question, rather than pointing the finger at the government saying ‘What are you going to do?’ you know…which was kind of nice in a way. And I think everybody, everybody at the screening loved it. You know everybody laughed, everybody cried. So, I think it worked.

You know there's… there's the classic exotic…exoticism or whatever it is. You know … people still, that's …why cinema and television was invented because you had access to places you could never go to.

…I think indigenous cinema - not only in Australia but around the world - Aboriginal cinema is this fresh, exciting, invigorating thing of new storytelling, new places, new doors being unlocked and gates being opened for …people around the world to see something that they, they've never seen before, you know. It's interesting places, you know, it looks like the National Geographic's sort of given up on fucking tigers and elephants because, you know, they've just done 200 years of that crap. Now they're looking for all the blackfella stories and it's … a really interesting concept. But the world's like that in a sense as well, you know. They want, they want to see a world that they they've never been to, or a way of looking at the world that they've never seen before. And actually the timing is to do, I think a little bit with how there's this you know, we we're killing the earth through resources and you know, and … sort of corporations becoming gods and all that kind of stuff – and… the world is sort of lost. You know, it's sort of, it's a little bit off the path at the moment. And people are looking for … how to get back on the path, and they sort of, I think they're looking for indigenous storytelling to find how to get back on that path and how to how to reconnect with your soul and your spirit in a sense, and how to reconnect with the earth. And there's a lot of that in indigenous storytelling: we have that everywhere, whether it's Samson and Delilah or you know, you know, what we were talking about you know, about outstations and getting you know getting back to country because it heals. I think the world's trying to get back to an outstation in a sense - and they're finding that at least a door to that outstation through, through cinema, and through television - through indigenous cinema and television and they're enjoying it, you know. So that's …why I think it's working, and I think that's why there's a connection being made with people around the world who are stuck in high rises in New York, and they're seeing this old man sit under a tree in, you know, … in the Western Desert and he's telling this story about astral travelling, you know, and how he enjoys it, and this person in this New York sky…you know, skyscraper, high-rise is just going ‘Oh my God where's my astral travel?’ You know what I mean: ‘Why can't I do that? How can I connect with it?’ - you know, I think there is that, you know we've got these incredible stories that people are….searching for, to heal them, in a sense. And I think Aboriginal filmmakers around the world - their storytelling can heal like that.

It's been interesting because of the success of Samson and Delilah and you know, I've had a pretty bloody good life as a filmmaker and as a cinematographer - whether it was right at the beginning you know shooting Satellite Dreaming to where we are today - and it's kind of like, because of the success of Samson and Delilah, there is a lot of pressure on the new film, the new ideas, and all that kind of stuff. So, I've kind of slowed down. You know, there was that kind of ‘You got to make two films a year now because of you’re hot…’ ‘Oh, fuck that!’ - you know what I mean, ‘Let's, let's make one film every five years, and just enjoy it in a sense…’