An Introduction

to the essays, by Tony Dowmunt

…is to provide a place for people to debate in more depth the histories and themes that emerge from the content of the rest of the site.

Of course, Satellite Dreaming Revisited can give only a partial and limited picture of the issues raised by and since the original programme, and so, as I say elsewhere, it probably excludes many relevant and important points of view, debates and examples of work. In particular I'm aware, and sorry, that only one of these essays is authored by an Indigenous person; also, that there isn't an essay looking in depth at the wide transformations brought about by digital media, or more specifically on the developments in television drama. For all these reasons, I'm keen to add contributions to the Essays, as well as to other pages. If you are interested in contributing (in whatever way), please go to the Feedback section at the bottom of the Credits page.

Originally I was interested in collecting contributions to form a printed book to accompany the website. In the end I decided that it would be better to publish online, on this site. There are many advantages (or 'affordances', in the current jargon) to online publication, including the capacity to add links to other material, both within and outside the publication site. This capacity obviously also includes audio-visual material, stills and moving images, both as links and embedded in the text itself. This excites me because I'm often frustrated by published texts about film, video or television which, through the limitations of print, deny the reader an experiential insight into the audio-visual world that is being described and analysed.

In addition, the online format gives us the flexibility and opportunity to be able to add contributions to the site if and when the need arises.

Lastly, I wanted to give the contributors (including myself) more stylistic freedom than is ordinarily available in academic publishing. As will become clear as you read, the essays range from the personal and anecdotal, to the more polemical and analytical - often in the same piece. I think that this diversity - of different voices and modes of address - gives a more nuanced and 'truthful' picture, than is possible if they all had to be delivered in the same tone and style.

For similar reasons, I didn't give a very specific brief to the contributors who agreed to write essays, but in the main offered them an opportunity to write what and how they wanted, responding to their experience of the last few decades in the field.

In the first essay Michael Meadows gives a richly illustrated and very personal account of his long career as a writer and researcher into Indigenous media. He provides an engaging personal and autobiographical gloss on the key texts he has co-authored, particularly Developing Dialogues [1] and Songlines to Satellites [2].

His essay also has a much wider geographical spread than most of the rest of the material on this site, offering insights from his research which has ranged from the Torres Strait Islands to Inuit media in Northern Canada. One of the conclusions he reaches on his journey (at the end of an account of a visit to Yuendumu in 1993) is that

it is the process that defines cultural production, rather than the content or the media themselves. When I think about it, I can see how this notion defines every successful First Nations production centre I have visited [3].

The centrality of 'process' over 'product' - an emphasis on the way media are made rather than on their outputs - is a principle that is shared and discussed across the field of alternative and community media throughout the world.

However, the essay finishes on a note of caution, acknowledging that

in both Australia and Canada there is still much to be done in recognising indigenous broadcasting access rights in terms of prior ownership and the subsequent effects of dispossession. But despite the infinitesimal policy movement in such areas, First Nations people from both countries have demonstrated the empowering possibilities offered by new communication technologies [4].

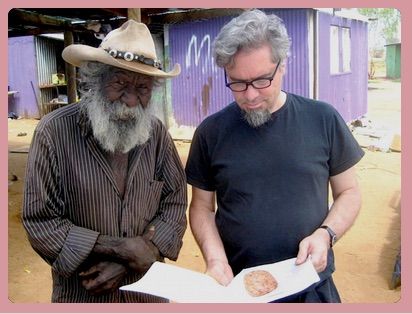

Michael's caution is echoed and amplified by Philip Batty in his essay, in particular in relation to the dire 'effects of dispossession'. Philip explains how even today 'many indexes measuring Indigenous well-being continue to show a persistent lack of advancement and in some areas, a steady deterioration' [5].

This is despite the fact that he and others

did successfully manage to build the foundations for the extensive Indigenous media sector we see today […] it is composed of a wide range of services at remote, regional and national levels, and on the face of it, seems to be flourishing. Yet, the uncomfortable question […] still remains: why, despite this and many other efforts to improve the lot of Aboriginal people, does poverty and dysfunction remain a daily reality in large sections of Aboriginal Australia? [6]

In his essay Philip first offers a clear and critical account of his own ground-breaking work in the development of the Indigenous media sector, then returns to his question above, acknowledging that answering it 'is a complex business and not easily dealt with in a relatively short essay' [7].

One answer he suggests is growing economic inequality (a problem shared across the neo-liberal world, of course), which, in Aboriginal Australia, has meant that 'while incomes for the urban Aboriginal middle class rose significantly between 2011 and 2016, incomes for those in remote areas actually fell' [8].

Nevertheless, he argues that

The problem of inequality is only one of the possible answers to the question posed at the beginning of this essay: why does dire poverty continue to exit in Aboriginal Australia despite years of government investment? In my estimation, one of the other major issues that contribute to ongoing Aboriginal disadvantage is the problem of what can be broadly described as Aboriginal community governance [9].

However, he is not promoting a return to the policies of 'self-determination' in community governance that were so dominant when Satellite Dreaming was made:

I am not arguing that Aboriginal organisations, should be run exclusively by Aboriginal people as the original policies envisioned. […] the problem with these bodies is that they were developed and continue to exist in accordance with unworkable policy frameworks [10].

He suggests that these frameworks continue to foster a form of community governance in which there is 'a sometimes complete disjunction between these bodies and the people they were meant to serve' [11].

In her recent Preface to her 2002 article, Melinda Hinkson also points out how community governance (in Yuendumu specifically) has been transformed for the worse over the last few decades. She comments that 'The semblance of control [Eric] Michaels passionately argued for has been filleted away, layer by layer' and that, echoing Philip again, 'Warlpiri daily life is punctuated by a ceaseless cycle of premature deaths, chronic illness, hunger, stress, and increasing rates of incarceration and punitive surveillance' [12].

I asked Melinda if we could reproduce and update her 2002 article here because it describes her experience in Yuendumu in the decade immediately following the production of Satellite Dreaming, and her consequent and insightful critique of Eric Michaels. His work, she points out, was

important in establishing a whole way of speaking about indigenous media practice, a discursive frame that extended out from Yuendumu to encompass activity occurring across the breadth of remote indigenous Australia. At the centre of this discursive frame sit the concepts of political resistance and cultural maintenance [13].

Both of these concepts, I think, underpinned our thinking as we made Satellite Dreaming, so her critique offers insights into some of the assumptions and inadequacies in the original programme. At the risk of simplifying her complex argument, she details processes in Warlpiri life that she thinks Michaels didn't see or account for, because of his focus on community control of media resources. Countering this, she outlines the importance of an 'inter-cultural' or 'bi-cultural' domain between Warlpiri and whitefella society, and advocates a more nuanced relationship than Michaels' concepts of resistance and cultural maintenance allow:

Warlpiri people are by no means passive observers of the transformations sweeping their world. Their ongoing engagement with new technologies suggests that at least some Warlpiri people see benefits in the new forms of articulation with the wider society that accelerated globalisation carries with it. For some there is a clearly understood political imperative to engage, for others, such engagement is comprehended as the product of a history that cannot be wound back. There is little question of ‘control’ in the way that Michaels articulated it [14].

Frances Peters-Little is another writer who has deeply influenced my own thinking about Australian Indigenous Media since making Satellite Dreaming. Her essay Nobles & Savages on the Television updates an article (also from 2002) that explored the polarity of the 'noble' and 'savage' stereotypes as they have been applied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, historically and up to the present in cultural representations of all kinds, including on television. Her references are mainly to 'mainstream Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander film and television films and programs' [15], to counter what she sees as writing with an undue focus on media produced in central Australia, to the detriment of that produced for mainstream television.

As she says:

In terms of reading material, the vast majority of the 158 articles catalogued by AIATSIS under the heading of Aboriginal television, focus mainly on Aboriginal television in central Australia even though the majority of programs are produced by urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers working for mainstream television. Of the total number of articles listed in the Murdoch Reading Room bibliography of Aboriginal television, the overwhelming majority of articles also emphasise a focus on community television in remote northern and central Australia [16].

This imbalance - between remote media and mainstream television documentary - was also reflected to some extent in Satellite Dreaming, an issue which I explore a little in my own essay. Frances' contention is that there is a 'noble focus on the ‘real’ Aborigines in northern and central Australia' [17], reinforced by Eric Michaels' view that 'Aborigines in northern and central Australia have culture but urbanised Aborigines do not' [18]. Her argument is that 'in recent years the noble pole has intensified to counteract past representations of Aborigines as savages and that the noble pole is just as damaging as the savage pole, simply because Aboriginal people are neither noble nor savage' [19].

Her work as an Aboriginal filmmaker has been to grapple 'between the noble and savage poles, with all the muddy parts that exist between the two, in search of a better way to tell stories about our people' [20].

Daniel Featherstone’s essay is a personal story in two main parts, the first an account of his role as the Media Coordinator at Ngaanyatjarra Media from 2001-10, then, in the next decade, his involvement in national Indigenous Media organisations, culminating with FNMA (First Nations Media Australia) - although his active engagement with the various 'peak bodies' in the sector spanned both decades.

He writes about arriving in the remote community of Irrunytju 'as Ngaanyatjarra Media’s only full-time non-Indigenous staff member' [21], then goes on to describe his nine years of remote community-based remote media work. His experience is a prime example of the kind inter-cultural engagement Melinda describes in her essay about Warlpiri media, and involved close collaborations with, among others, Belle Davidson, Noeli Roberts, and Simon and Pantjiti Tjiyangu. Noeli, Simon and Pantjiti are key characters in Satellite Dreaming and are featured on this site.

His time with Ngaanyatjarra Media delivered a massive expansion in their activities, 'spanning radio, video production, IT, training, music development, cultural projects, events and technical services' [22], leading, in 2008, to the construction of a new Media and Communications Centre with 'dedicated spaces for a community access telecentre, two radio studios, TV/music studio, archive facility, video edit rooms, meeting room, offices, server room and enclosed vehicle and equipment storage' [23].

His job in Irrunytju also involved working nationally with IRCA (the Indigenous Remote Communications Association) and ICTV (indigenous Community Television). In 2010 Daniel moved to Alice Springs and began a closer association with IRCA, and a more active role in national organising, leading to the transformation of IRCA into a new national peak body (FNMA) to 're-build cohesion and shared direction within the deeply divided national First Nations media sector' [24]. As well as outlining his role in FNMA, Daniel also describes related national initiatives such as the Converge Summits [25], and the National Remote Indigenous Media Festivals [26].

In explaining why 'why First Nations Media matters', Daniel takes his cue from the Aboriginal people he has worked with. Belle Davidson explained: 'This culture will not die out, it will always be here. We keep on making new videos of those Tjukurrpa stories with the people who are alive today' [27], and Jenni Enosa (Chairperson, Torres Strait Islander Media Association, and IRCA Director) commented that

Indigenous media is about empowerment of Indigenous people at grass root level, improved health and lifestyle, employment opportunities for our people. Also empowering young people so they’re not turning towards negative stuff and Americanism, they can take a different approach towards cultural maintenance, keeping Indigenous languages and culture alive in this country. It’s about preserving our culture and identity, […] supporting people to live where they belong [28].

In Faye Ginsburg's essay (forthcoming) we move from questions about remote media, to the internationally celebrated filmmaking career of Warwick Thornton.

Warwick is a Kaytete man born and raised in Alice Springs, who as a young man worked at the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), and was the cinematographer on Satellite Dreaming. Faye will argue that in all his different films his 'narratives revolve around a karmic sense of the consequences of actions that decide the future fate of his central characters’ lives, including (most recently) his own.'

Finally, I make three contributions to these pages, the first was written in 2021-22 towards the end of the process of making this website, and the two Appendices further back in 1997 and 2015. These last two (Heat from a small fire and Will it harm the sheep?) are on this site to make the history of my own involvement in the area (hopefully) clearer and more transparent. I refer to how I've learned and moved on from them in the first essay (Revisiting Satellite Dreaming), so I won't add to that here.

My aims in the first essay, Revisiting Satellite Dreaming, are twofold: to give an account of how and why I developed this website, and then to introduce a few of the major themes and issues that emerged for me in the process of making it, over the last decade. The account is deliberately personal, not least because, as a non-Indigenous person from the other side of the globe, I wanted to be clear about my role in the work. Like Linda Tuhiwai Smith, I don't believe that

colonialism is over, finished business. This is best articulated by Aborigine activist Bobbi Sykes, who asked at an academic conference on post-colonialism 'What? Post-colonialism? Have they left?' [29]

We haven't left. As a whitefella from Australia's colonising nation, I'm acutely aware that however much I want to ally myself to the struggle for Indigenous media, I remain a privileged outsider. As such I think it's important for me to write personally so my own 'subject position' (with whatever unconscious prejudices accompany it) is opened up for scrutiny. This is why my essay ends with an account of a dream I had when I started working on this project.

The first part of my essay is the story of the making of Satellite Dreaming and the development of the Satellite Dreaming Revisited website, from my point of view. Then, in my discussion of the themes and issues that emerged for me in the process of making the site, I rely heavily on comments made by my interviewees during my conversations with them, or in what they have written. I'm hoping that this 'polyvocal' quality, embracing many and diverse voices, is both inclusive of, and encourages dialogue between, the sometimes polarised communities in the Indigenous media sector. I summarise my conclusions [30] from these conversations in my essay, so won't repeat them here.

The essays on these pages give reasons for both optimism and pessimism. Taken together, I do think that they stand as both a celebration of the massive achievements of Indigenous media, as well as an insightful analysis of the substantial challenges facing these kinds of media face in the future, both in Australia and, by implication, worldwide.

The essays pose fundamental, globally relevant questions like: what are media for? And how can we organise them so they promote genuine social dialogue between all communities - including, most importantly, those communities (like First Nations) that have historically been excluded from, and misrepresented in, the mainstream conversations?

This is a history that has only just begun to be written.

Footnotes

Forde, S., Foxwell, K. & Meadows, M. (2009) Developing Dialogues - Indigenous & Ethnic Community Broadcasting in Australia, Bristol, UK / Chicago, USA: Intellect

Molnar, H. & Meadows, M. (2001) Songlines to Satellites - Indigenous Communication in Australia, the South Pacific and Canada, Annandale NSW: Pluto Press.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, first paragraph.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, first paragraph.

From here, paragraph 3.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 5.

From here, paragraph 3.

From here, paragraph 2.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012), Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, London: Zed Books, p25.

Forde, S., Foxwell, K. & Meadows, M. (2009) Developing Dialogues - Indigenous & Ethnic Community Broadcasting in Australia, Bristol, UK / Chicago, USA: Intellect

Molnar, H. & Meadows, M. (2001) Songlines to Satellites - Indigenous Communication in Australia, the South Pacific and Canada, Annandale NSW: Pluto Press.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, first paragraph.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, first paragraph.

From here, paragraph 3.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, final paragraph.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 6.

From here, paragraph 1.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 4.

From here, paragraph 2.

From here, paragraph 5.

From here, paragraph 3.

From here, paragraph 2.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012), Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, London: Zed Books, p25.