Dreaming Tracks & Digital Futures

Reflections on three decades of Indigenous media research, by Michael Meadows

The rain squalls beating down on the tin roof are increasing in intensity, along with my anxiety levels. It seems as if the monsoon has finally arrived on Boigu, a small island in the Torres Strait, a few kilometres from Papua New Guinea. It's December 1992 and I'm on my second visit to the Torres Strait. You can't get much further north than here and still be in Australia — officially, that is — local communities have always seen the border with Papua New Guinea as a suggestion rather than a rigid administrative boundary. They've been plying these waters, exchanging goods, travelling, and otherwise cementing family kinship ties for upwards of 2500 years.

A typical BRACS facility in the Torres Strait, 1992 (this and all subsequent photos: ©Michael Meadows)

But my visit here has ended prematurely. This morning, my research assistant, Ivy Toby, politely explains that an important person on the island has passed away and that a mourning period has begun. It means that everyday life on the island will shift to support this important ritual observance. Ivy is my key contact here — as well as the local radio broadcaster — who has been introducing me to everyone we encounter on our walks around the island over the past three days. It is an effective 'chance meeting' approach to gathering information about community perceptions of mainstream television and its impact — my primary reason for being here. Although initially, I'm disappointed that several days of research time will be lost, it's a salutary reminder of the nature of cross-cultural research: I'm the outsider here, invited into the community as a guest and am obliged to conform to community expectations.

The next day dawns fine but with thick, billowing cumulonimbus clouds, heavy with rain, boiling above Papua New Guinea. The sound of an aircraft. A single-engined Cessna. I watch the pilot circle the airstrip before dextrously negotiating the slippery runway — a perfect landing. I've already farewelled my friends on Boigu and within minutes, I'm aboard — the only passenger — and we are flying low along the Papua New Guinea coastline before turning due south towards Horn Island Airport — the service centre for the Torres Strait and northern Peninsula region of Queensland — 150 kilometres and about 90 minutes' flight time away. I look back through low cloud at Boigu — a tiny island nestled on the edge of the Arafura Sea — and wonder what the future holds for its 250 permanent residents.

Coming of the Light memorial on Murray Island, Torres Strait

The arrival of representatives of the London Missionary Society in 1871 is celebrated on July 1 each year throughout the Torres Strait as the 'Coming of Civilisation' or the 'Coming of The Light'. Christianity has had a profound effect on Torres Strait Island people: every single inhabited island has a monument commemorating the event; no aspect of life in the Torres Strait is unchanged by the coming of religion (Schnukal, 1987).

Some see the coming of television as a possible saviour of Torres Strait Island culture while others view it as the intrusion of western values into Islander society — potentially the last nail in the coffin. Mainstream television arrived in these remote islands in 1987 and my first visit to Thursday Island 12 months after this had been at the invitation of one of the key members of the Torres Strait Islanders Media Association, Aven Noah. My aim was to explore some of the perceived impacts of mainstream television on island life.

My visit coincides with the the Torres Strait Island Cultural festival.

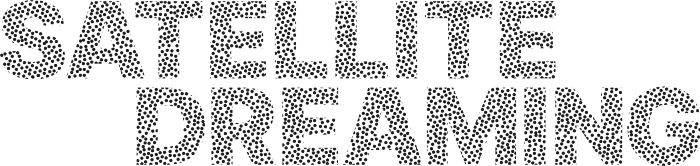

Thursday Island & Torres Strait Cultural Festival 1992

There's a gale warning and gusty SE winds raise dust clouds across the festival grounds amidst the throb of diesel generators. A man walks past with a T-shirt reading Dinki Di TSI as a huge speaker crackles and the ABC News blasts through the public address system set up on the school oval. Technically, the switchover from ABC Radio Cairns to Radio Torres Strait is hardly noticeable but the content, following on from the 3 p.m. edition of the ABC news-in-brief, could not have been more different: a few minutes of Island news — read, not in English, but in Torres Strait Creole or Broken — followed by a selection of locally-recorded, locally-produced songs from some of the 200 or more islands between Cape York and the southern coastline of Papua New Guinea.

For two hours each weekday afternoon, life on the 14 inhabited islands virtually grinds to a halt as Radio Torres Strait goes to air. But this afternoon is special — the broadcast is live for the first time from the Second Torres Strait Island Festival. As Islander voices echoed around the oval, people seem to smile more, the children's activity seems even more frenetic and groups in the stalls at the festival grounds begin to sing along. It is undoubtedly their radio, their voice (Meadows, 1988).

Mainstream television reached the Torres Strait two years after the launch in 1985 of the Australian telecommunications satellite AUSSAT and 13 years after its Canadian equivalent, ANIK. Both caused a similar degree of concern amongst remote First Nations communities.

Torres Strait Cultural Festival 1992

Virtually overnight, English-language television broadcasts were perceived to threaten existing Aboriginal languages and cultures (Molnar and Meadows, 2001). My first visit to northern Australia confirmed that the arrival of satellite television in the Torres Strait had already impacted negatively on communities, shortening working hours as people became transfixed by TV soaps. Children had begun to emulate their 'TV heroes' by carrying knives and getting drunk, and community meetings had become all but impossible to organise because people preferred to stay home to watch the box (Meadows, 1988). But at the launch of the multilingual Radio Torres Strait during that same visit, Torres Strait elder Getano Lui Snr observed:

'Before, we sent letters to the other islands. Now it's instantaneous. Now we send songs… The younger people who could write letters, that was the only contact they had with the other people but now, they can hear and listen as somebody is talking and not only that, but it also educates our younger people to speak, how to pronounce words — it's very good, it's part of education.'

An audience study 15 years later revealed that, despite the power of mainstream television, Indigenous-controlled community radio continues to provide a first level of service to communities across the Torres Strait and throughout Aboriginal Australia (Forde, Foxwell and Meadows, 2009).

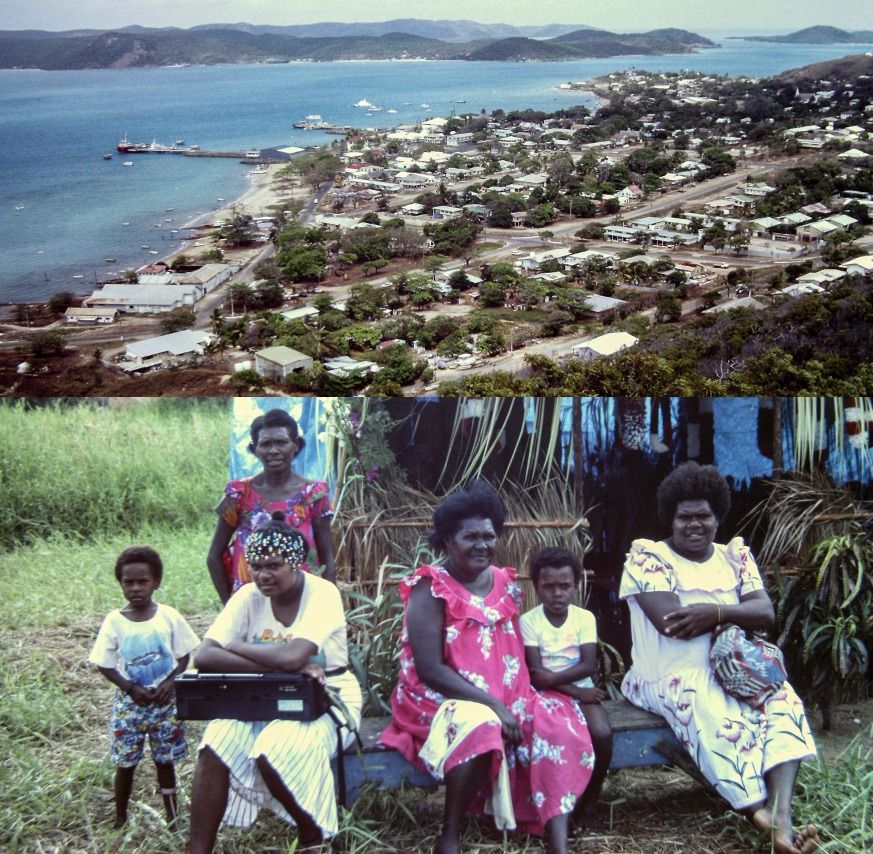

Torres Strait Islander Media Association BRACS coordinator Aven Noah

Aven Noah's patient guidance helps to shape my understanding of First Nations media research and to identify methodologies that I subsequently apply over the next three decades — aligning visits with community time frames. He knows that the Torres Strait Cultural festival is an ideal opportunity for me to observe and explore various dimensions of Islander culture, as well as having the chance to speak to a wide range of people from the outer islands who traditionally gathered on TI — Thursday Island — each year for the event. An interview on Torres Strait Radio plays a critical role, informing everyone listening that I was there at the behest of TSIMA (Torres Strait Islander Media Association) and thus 'authorising' my presence. Later research with Christine Morris reinforces the same elements of actively engaging with communities but with an added dimension — reciprocity. It entails seeing research activity as an exchange rather than an information-gathering exercise and it challenges us all to consider our place in the research process. What can we give back to the communities who are giving us the information we seek?

Radio Torres Strait studio on Thursday Island, 1992

I return from the Torres Strait in 1988 with many unanswered questions about the role of media but later that year, my pathway into academia takes a decisive turn when I enrol in a research Masters at Griffith University.

It was then I meet visual anthropologist, Eric Michaels. He is already ill from the debilitating effects of HIV but at our first meeting, he hands me his only copy of a monograph he has recently published — Aboriginal Invention of Television: Central Australia 1982-1985. He suggests that I read it and then come back to discuss my project. We meet just once after that when sadly, his illness becomes more acute. Although too ill to supervise my emerging study, his shared insights inspire me to pursue a similar trajectory. His ideas seem to engage with my growing list of unanswered research questions more than any other academic work I have read to that point and it becomes an important framework for my subsequent studies.

It's my first visit to Canada's North — the region north of 60 degrees. I'm travelling with my Canadian host, Shannon Avison. A Journalism professor at the Saskatchewan Federated Indian College in Regina, we connected through email and letters before my visit and now we are heading north in her ageing VW Khombi with a broken heater — in the middle of winter! Outside, a white winter landscape stretches to the horizon, covering the open plains of the prairies. Big sky country. We drive through bare fields shorn of wheat with occasional tall dark angular buildings — grain elevators — interrupting the skyline.

Northern Saskatchewan in Winter, 1991

A cold Saskatchewan wind outside is cruel and cutting. I can feel it creeping through cracks in the Khombi and my breath is frosting. I've never felt so cold. The sun is about 20 degrees above the SW horizon and I can't get used to it being in the south. The van is buffeted as we drive into a sunset of delicate pink and orange. The temperature is falling further and the Khombi's windows are starting to frost up. Despite sitting inside a sleeping bag, my legs are numb and have been for about an hour. This is the North in winter.

Next morning, we mercifully manage to hitch a ride on a Sask-Power Super King Air flight to the remote northern township of La Ronge, set beside a huge frozen lake. The snow squeaks underfoot as we walk from the aircraft. It's minus 28 degrees and it's there I meet Nap Gardiner, a La Ronge Cree who is deeply involved in the Native Communications Society — a First Nations organisation that supports Native broadcasting across the country. I made contact with Nap by letter from Australia, months ago, and he's invited me to visit his Cree radio station. The first thing he wants to tell me is about his experience he had a few weeks ago, driving back alone to La Ronge late at night in a blizzard. He turned on CBC Radio and heard a didgeridoo playing. 'I heard everything in that sound,' he explains. 'It nearly knocked me through the roof of my car.' He wants to connect with Aboriginal broadcasters in Australia and talks about possible program exchanges. He already knows that Aboriginal people in both countries share many cultural dimensions. Here in La Ronge, he and his team maintain a regular radio program in Cree, keeping local communities informed of important news and information. To them, it provides a first level of service — it was a term I was to hear again and again across the North. But equally, it is how the station management is configured that is crucial — representatives from across the region ensure that the communities’ voices are being heard.

It's mid-March before I'm able to organise an expensive trip to Canada's largest island. The township's previous name was Frobisher Bay, changed to Iqaluit — place of many fish — just four years ago. The three hour flight from the Canadian capital, Ottawa, to Iqaluit again highlights the vastness of the Canadian landscape and provides an insight into how it has shaped the kinds of communities and communication that define Aboriginal people here. Almost as soon as we leave Ottawa, we're flying across the Canadian Shield — a vast expanse of some of the oldest exposed rock on earth, scraped clean by tens of thousands of years of glaciation leaving behind tens of thousands of lakes. Now, all of them are iced-up for the winter. And then we cross the treeline into the tundra and the white, almost featureless expanse of the North. The jet begins to descend and we cross Hudson Strait, a mass of crazy zig-zagging ice patterns with a few open channels. It's almost impossible to estimate how high we are until we finally touch down in the northern city of Iqaluit, population 7500, at the head of Frobisher Bay. The first thing I notice as I squeak through the snow at minus 18 degrees is Ravens — Crows — even up here. They look the same as the birds that can withstand the blistering heat of Central Australia! The water surface on the Bay is frozen into waves. Iqualit has several significant high-rise buildings above a sprawling mass of functional smaller dwellings. They look a bit like shipping containers from the outside but are designed for survival in the extreme climate.

Iqaluit, Baffin Island, 1991

Most of the inhabitants here are Inuit — a diverse people with eight ethnic groups, speaking five dialects across the North. Although Inuit have lived in parts of the Arctic for around 4000 years, some were forcibly moved to more northern and remote areas during the 1940s to strengthen Canada's claim on land in the Arctic. It forced previously nomadic people who moved according to the availability of food resources like caribou to become sedentary and many of the early remote settlements bordered on starvation for years until they became accustomed to their enforced new environments. Like First Nations people further south, Inuit children, too, were removed from families and sent to residential schools as part of Canada's assimilation program. This resonates strongly with the treatment of Aboriginal people in Australia and echoes the impacts of the Stolen Generation. Indeed, one of my research contacts, Ray Fox from the James Bay Cree, told me a story of how he and several of his friends were lured aboard a government light plane that had landed on a lake one day at his village in northern Alberta. He was finally reunited with his mother almost two decades later. The horrors of the residential school system have recently re-emerged with the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of children who died while in State 'care'.

I meet Inuit Broadcasting Corporation producer Blandina Makkik who talks excitedly about a new pan-Arctic television service for Aboriginal communities — Television Northern Canada (TVNC). The Native Communication Societies have already set up five production centres across the North, each designed to uplink video to the new channel during prime time because of Canada's five time zones. She describes Inuit television as 'different' to what you might see on the only other broadcaster here, the CBC. Smaller communities like Igloolik and Rankin Inlet — in the high Arctic — produce 'Inuit-style' TV: time pauses, programs that are slower in pace and which feature more traditional subjects like Shamanism. She tells me about her recent trip to meet the Siberian Inuit. Initially compelled to use a Russian government translator, she gradually realised that she could understand then dialect spoken by her Siberian brothers and sisters — and they were able to speak to each other directly, much to the chagrin of the government official. She gestures towards a map of the world on the wall of her office. But this circumpolar perspective is one I’ve never seen before. Taken from above the North Pole, looking down, it reveals the tips of continents that stretch into the high arctic — a geographical and cultural bond that transcends political boundaries.

18 months after my return from Canada, I'm back in the Torres Strait with an expanded research agenda. This time I visit 14 islands, including extended stays on Murray and Boigu.

Murray Island showing the BRACS facility [radio mast just visible] on a mountain ridge, high above the main community centre, 1992

Five years after its implementation on the mainland, a scheme called BRACS (Broadcasting for Remote Aboriginal Communities Scheme) has been rolled out across the Strait. It's essentially a basic media switching centre, allowing communities to interrupt incoming satellite mainstream television signals and, if desired, insert their own locally-produced video and/or radio programming — in theory!

But when I visit, most of the units installed on the islands are either inoperative or damaged or both. A lack of funds for maintenance and training has meant that only a handful of communities support a local broadcaster to operate what is potentially their local community radio or TV station. There's frustration expressed at the waste of a potentially valuable cultural resource and stories of poor communication and inappropriate siting of BRACS units are common. On Murray Island, for example, the BRACS unit is located on top of the highest point on the island, about as far away from the village as possible, meaning that few people have ever made the steep climb up to be interviewed or to participate.

Aven Noah (left) and Jim Kabere and the Murray Island BRACS station, 1992

On most of the island BRACS units, a lack of a basic air-conditioning filter has meant that almost all suffer from salt air corrosion. The list goes on. But despite these setbacks, several of the islands are producing quality programming for their communities. On one island, a videotape of a tombstone opening ceremony was broadcast locally, replacing the mainstream television signal. Such important events are usually held two years after the death of an island resident and typically involve everyone on the island. In this case, the same video was broadcast non-stop for two weeks until an island elder politely suggested that perhaps it was time to resume mainstream programming.

My Torres Strait visits confirmed that like Canada's North, community life here had changed with the arrival of mainstream television. Attempts to provide communities with an alternative had largely failed although there were signs that creative efforts by some and the formation of a representative Indigenous media organising body were about to impact on the future. Torres Strait Radio is already well-established and Aven explains the importance of including representatives from the three main island language groups — to ‘authorise’ the content being produced.

Australia's first capital city Indigenous community radio station, 4 AAA (now 98.9 FM) goes to air. The Brisbane Indigenous Media Association is awarded the licence following a long lobbying process and today it remains one of the country's most successful community stations with its country music format. Officially launching the station, former federal Liberal Senator, Yuggera elder Neville Bonner tells listeners: 'This is a very important day in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Queensland. The Murri Hour began in 1984 on 4ZZZ [Brisbane's first community radio station]. We've had a great relationship with 4ZZZ. Aboriginal people have always had someone else to make our decisions. Those things are changing. It's time Australia recognises that Indigenous people have come of age. If there are going to be policies for us we should have some, if not all the input. Aboriginal people will be broadcasting to all but more specifically, to our people. We'll be telling our people. This is our radio station. You are hearing our voice.' (Forde, Foxwell and Meadows, 2009).

I took part in numerous preliminary meetings in the lead-up to this momentous day and it’s clear that the organisation of the governing structure for the radio station is central to its operation. Members of the Board — senior members of then local Indigenous community — are never or rarely heard on air: their role is to ensure that the station meets its cultural obligations and on-air presenters are reminded of this when they stray away from that objective.

I'm due to submit my PhD in three weeks and I'm feeling a little nervous. Although my research thus far has involved several field trips to the islands of the Torres Strait in North Queensland and a five-month sojourn in Canada's North, this is my first extended visit to a remote Aboriginal community in mainland Australia. I'm on my way to Alice Springs, the centre of the continent for settler Australia but the centre of the world for millennia for the 250 Indigenous nations who have inscribed every element of this ancient landscape into their cosmologies. From above, it looks to be an empty land, a wilderness – terra nullius. But, of course, that is an illusion. The haze reminds me of flying north into the Canadian Arctic but everything here is tinged red and orange, the colours of heat. There, I was flying north into whiteness but here it's a rich palette of coastal greens and now, baked browns and greys. In Canada's North, the planes are half-filled with freight but here, it's tourists. The clouds are thinning as we cross the channel country — like a dot painting with its changing colours and patterns. Drying waterholes and dams below are tinged with blue-green algae. The channels morph into salt pans — the edge of the Simpson Desert. Alluvial fans stretch to the horizon. This is the centre, a transition zone, smoother than the treeline in Canada's North. Below are the red sand dunes of the Simpson Desert. They stretch like frozen waves of ochre dotted black with the shadows of trees — giant ripples in a waterless ocean.

In Alice Springs, I collect a four-wheel-drive hire vehicle and, as agreed with my Yuendumu contact, Peter Toyne, meet up with Warlpiri residents, Robin Granites and his wife, Alma. Robin was one of the founders of the Warlpiri Media Association and I've read about him in Eric Michaels' writings. Although I'm ostensibly giving them a lift to Yuendumu — 300 kilometres northwest of here — I suspect that the meeting was arranged by Peter to make sure I get there safely. Although I had wanted to visit Yuendumu ever since reading Eric's publications, I didn't think it was really necessary for my own research project. But I seem to have inadvertently come full circle. The long drive through the deep-red sand-drifts of the Tanami Desert confirms all that I have heard and read about the remoteness and the miracle of Indigenous survival. My attempts at making conversation are largely unsuccessful so I relax and settle into the journey. Robin and Alma are already fast asleep.

Media production centre at Yuendumu, 1993

I'm visiting this community of 1100 at the invitation of Peter Toyne who is manager of the Tanami Network — a compressed videoconferencing system that links 12 linguistically similar groups in remote Central Australia. Designed initially for business use in the mainstream, the Warlpiri have appropriated it to enable face-to-face communication in real time across the vastness of Central Australia. The communities quickly embraced the technology and have used videoconferencing to sell their iconic dot paintings to international dealers and galleries. But the Tanami Network is much more than that, with around 30 different applications identified by its designers, including monitoring crime in the community, health management, education, providing local information, organising social ceremonial work, dealing with 'sorry business' (deaths), and strengthening family ties. The network is managed according to an existing community social structure that includes all of the skin groups that represent its diverse audience base (Meadows, 1994). I watch school children receiving a lesson via videoconferencing from Alice Springs and health administrators in Darwin delivering a training program to local health workers.

Warlpiri Media Association’s archive of videotapes — approximately 1,000 hours — in 1993

It's also connected with the pioneering Warlpiri Media Association, set up in 1984, having already produced around 1000 hours of original, local programs. I spend a day in front of a TV monitor watching some of the videos that the Warlpiri have 'invented'. Virtually all of those I see are shot in 'real time' with little or no editing — similar to the style adopted by the remote Inuit communities above the Arctic Circle in Canada's North and by communities in the Torres Strait. It seems to suggest a common First Nations' philosophy which is able to incorporate every aspect of landscape and life, including communications technology.

A week later I'm sitting in the late afternoon sunlight with a group of about 20 Warlpiri women, the camp dogs and a handful of non-Indigenous workers to observe some important 'finishing business' . It's for a senior Warlpiri woman who passed away two years before. It's the final of four nights of farewell rituals that pass on the spirit and responsibilities to her kinship group.

Through the rays of the setting sun they dance: children, teenagers, young women, old women — the Kudungurlu (workers, police) and the Kirda (bosses, owners of the stories).

Dawn as the ‘finishing business’ ceremony draws to a close at Yuendumu, 1993

They dance in skin/country groupings between two decorated digging sticks stuck upright in the sandy ground. It had been meticulously swept beforehand by two women using rakes and branches. The two sticks are joined by a hand woven ochre coloured string with feathers attached to it. The wind increases in strength and the temperature falls. Dust is everywhere and there's thunder in the air. Several of the many dances that ensue involve only one or two women. Between performances, they sit together, painting each other's bodies, accompanied by low-level chanting and murmuring — laughter and jokes intermingle with serious discussion. A Warlpiri woman sitting next to me explains in a whisper what each of the dances is about and she illustrates it by drawing with a stick in the red sand. The ceremony continues throughout the night and in the bitter cold of a desert sunrise, the women throw branches onto the fires that surround our circle and join for the last three dances of the cycle. Then they are crying and laughing and as they do, a local female community worker captures it on video — another recording for the Warlpiri Media Association's vast media archive. Then one of the Kirdu comes over to us and says simply: 'Finish.' Everyone smiles, knowing that obligations and responsibilities have been met. The cycle is complete.

On my way back to Brisbane, the Yuendumu experiences haunt me. I cannot pretend to fully understand the iconography used by the Warlpiri filmmakers but I can recognise that the videos they produce represent a powerful cultural resource reflecting a process that operates in many First Nations' communities. It is more obvious here at Yuendumu but it serves to reinforce what I’ve observed and experienced in Australia and Canada in my years of field visits: the programs being produced are not necessarily the main objective — it is the social organisation of how they are produced that defines them and it is evident in the absence of a barrier or boundary between producer and audience. As one Warlpiri video worker remarked; 'The audience are the producers here.' It is a crucial dimension — regardless of whether the program is in Broken, Meriam Mir or Kalaw Lagaw Ya in the Torres Strait; or in the languages of Canada's remote North — Chippewa, Cree, Ojibway, Dene, Inuktitut; or features programs broadcast across Central and Northern Australia in Arrernte, Pitjantjatjara, Warlpiri, Yolgnu; or in the English language programs produced by urban and regional First Nations communities across Australia.

And so this visit that I initially thought might not be necessary, confirms the inescapable conclusion that has emerged from countless conversations and observations since I started this journey — it is the process that defines cultural production, rather than the content or the media themselves. When I think about it, I can see how this notion defines every successful First Nations production centre I have visited.

I first meet Helen Molnar at a conference dinner around 1994. It is a select event hosted by the founding editor of Media Information Australia (MIA), Henry Mayer. A professor of political theory, Henry is across a broad range of academic disciplines and his pithy refereeing commentary on my article submissions is always precise and constructive. He enlisted his considerable intellectual powers and energy in 1976 to launch MIA which is soon acknowledged as the pinnacle of media journals in Australia. Henry is very good at networking — and at getting other people to network but it takes a year or so before Helen and I are able to work together. We are aware that our PhD studies overlap significantly with both of us exploring Indigenous media in Australia — my comparative case study, Canada and Helen's, the South Pacific.

Towards the end of the 1980s, Helen has set up a media consultancy business and wins an ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission) tender to conduct a review of the Indigenous media sector in Australia. I play a minor contributing role but maintain contact with her throughout what becomes a challenging process. She essentially puts her life on hold and manages to survive on her extraordinary drive and insistence on accuracy. Existing tensions within the Indigenous media sector surface at times which offer up further challenges but she produces an extraordinary report — Digital Dreaming. We both knew that without a high standard of proof, the findings will easily be swept aside by ATSIC, particularly if it does not meet expectations. The detailed report runs to more than 170 pages with around 130 recommendations but ATSIC is reluctant to publish it in full. Perhaps it provides too much information that could be directly related to the government agency's failings across the sector but for whatever reason, the report languishes for months. ATSIC eventually enlists former Australian Broadcasting Tribunal chair, Peter Westerway, to produce an edited version — essentially, the recommendations without any of the contextual evidence. It is a disappointing conclusion to what has been a massive task, drawing together information and resources from around the country.

Book cover

It is during this time that the idea for a joint book — Songlines to Satellites — begins to crystallise. I'm not sure if ATSIC's reluctance to publish the Digital Dreaming report is a catalyst, but we soon put together a book proposal and submit it to Pluto Press in Sydney. It is eventually published in 2001 but sadly, Pluto Press disappeared from the publishing scene in Australia around 2010 and Songlines goes out of print. But now it has a new life — on this very website!

For the next five years, I direct my research efforts into community broadcasting. Joining with colleagues Susan Forde and Kerrie Foxwell-Norton — and later, Jacqui Ewart. Susan, Kerrie and I, in particular, create a vast database of information around the Australian community broadcasting sector — its history, policymaking challenges, program formats and most recently, its audiences. Working with these two wonderful women is the highlight of my academic career. The idea for an audience study has been haunting us for a decade or more, particularly in relation to exploring the nature of the producer-audience barrier. Was this any different in community radio and television? How did this concept apply in Indigenous and ethnic communities? And how could Indigenous media production be defined? It sounds like a huge project — and it was. Kerrie is project manager and somehow manages to pull it all together. From the start, we establish clear lines of communication with our research collaborators and set up an advisory committee that meets each month with between 11-15 representatives from our research partners. And it works brilliantly (Meadows et al, 2007)! We are running over-budget but I insist on continuing with our plan as I know a project like this will probably never be repeated.

My primary responsibility is the Indigenous component of the study. I know from past experience that I will have to fit in with Indigenous community timelines and demands and although interviews and focus group discussions in the broader community broadcasting sector begin almost immediately, it is 12 months before we settle on a timetable for visiting First Nations communities. I’m starting to feel a little concerned that time is ticking away but have to trust in our sector representatives. Negotiations are crucial — unless Indigenous communities involved agree to the terms of the research processes, it is destined to fail. I recall vividly the icy day at a Melbourne conference in mid-2005 when the Chair of the Australian Indigenous Communication Association, Ken Reys, calls me up to a meeting with his key sector representatives in his hotel room. They look relaxed when I walk in. He turns over an envelope and on the back, draws a very accurate map of Australia. Two minutes later he’s sketched out the plan — which communities will be most suitable to visit and suggests timing around events, festivals etc. It is an agreement — and on the back of an envelope! The field visits can begin.

Indigenous radio played a critical role in North Queensland in the summer of 2004, when angry Indigenous residents of Palm Island — near Townsville — set fire to their local police station following yet another Aboriginal death in custody. To understand why this triggered such a reaction some context is important. A 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody investigated the deaths of 99 Indigenous people being held in detention around Australia. The inquiry produced a raft of reports and more than 300 recommendations, mostly centred around keeping Indigenous people out of prison. To date barely two-thirds of these have been implemented around Australia. Since the 1991 Royal Commission delivered its findings, 475 Indigenous people have died in police custody or in prison. It is that background that fuelled the anger on Palm Island in November 2004 (Meadows et al, 2007).

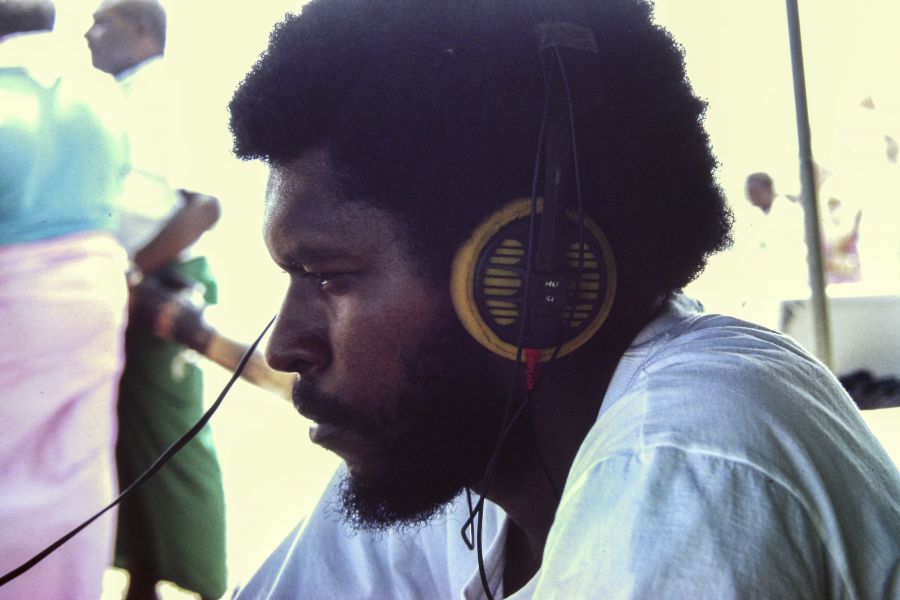

The Palm Island community from the air, 2006

From the air, it looks like a tropical paradise. 'Palm' is part of a group of continental islands off the far North Queensland coast that have spawned a collection of exclusive — and very expensive — tourist resorts. Within sight of Palm Island is the high-end resort complex of Orpheus Island, ironically separated from Palm by the notorious Fantome Island — a detention facility used for Indigenous people diagnosed with Hansen's Disease (leprosy) between 1940 and 1973. The Djagubay name for this island is Eumilli. Palm Island was declared an Aboriginal Settlement by the Queensland Government in 1914 and four years later, Indigenous people from across the State were forcibly sent here as it was considered to be a penal settlement for the first two decades of its life. People from around 60 different Indigenous language groups were forced together, creating inevitable tensions. Residents use the name 'Bwgcolman' for the island, which means 'one people from many groups'. This time I'm with Kombumerri research assistant Christine Morris. Because of the mostly negative media coverage Palm Island has received for decades, any non-Indigenous strangers are quite understandably treated with suspicion and Christine suggests that we ease our way into the community by simple 'being seen'. So we sit outside the main island store and our interviewees come to us as she has predicted. Once people satisfy themselves as to our bonafides they open up and willingly share their views on the importance of Indigenous-controlled media.

The events of November 2004 remain fresh in everyone's mind. It was the death in police custody of a young island man that sparked fury on the island. As mainstream media sensationally branded the incident 'a riot', Indigenous voices on local radio 4K1G in Townsville spoke about 'the resistance' with a Cairns-produced (Bumma Bippera Media) and nationally-broadcast talkback program, TalkBlack, providing listeners with views other than those from sources such as State politicians and the police — in short: 'black voices and black issues'. The program subsequently was judged best coverage of Indigenous Affairs at the 2006 Queensland Media Awards. One listener observed (Meadows et al, 2007):

'I think the only tool the community has to use is using places like 4K1G [Townsville] to make sure that what was being brought out of the Palm [Island] community as a whole was projected in the right manner, not in a negative manner. That's only one part of the importance of Murri media or Indigenous media. It provides places like Palm, Woorabinda, the Cape [York] and other Indigenous communities, particularly the Indigenous population in the mainstream, with a voice, a balance, projecting our stories, our culture, our language the way we want to hear it but giving it to the wider audience too, people who live in the mainstream, people who don't often come in contact with Indigenous people.'

It's been 13 years since I last drove out along the Tanami Highway. Indigenous research assistant Derek Flucker and I are on our way to the Yuendumu Sports Festival.

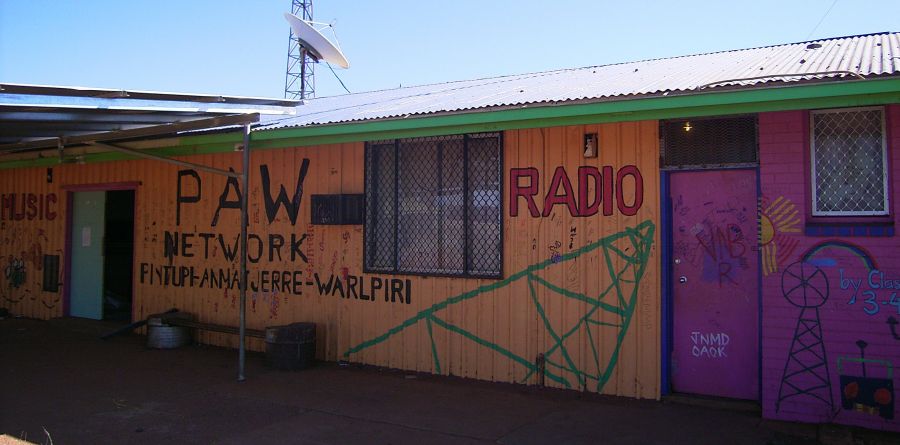

Research assistant Derek Flucker (centre) is interviewed on PAW (Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri) Radio at Yuendumu, 2006

Our methodology has been working well — following a timeline and structure set by the communities themselves has enabled us to be accepted and 'authorised'. The red sand drifts seem much the same but at one point we pass a camel that has wandered out onto the highway. It doesn't seem quite so far this time and in our well-equipped 'Troopie' [Toyota Land Cruiser Troop Carrier], we are self-contained — an important consideration when visiting remote communities where resources are scarce and expensive. When we arrive, Derek talks about our project on PAW (Pintubi Anmatjere Warlpiri) radio so that everyone will know who we are and how we fit into the community social structure. My research contact in Yuendumu and I have prepared a list of possible interviewees and when we meet one of them the moment we step out of our vehicle, I'm curious as to why our local host does not suggest we do the interview here and now. As we move around the community, it gradually becomes apparent that the order in which I must speak to people is determined by a cultural hierarchy — the Warlpiri way. It's another reminder of the existence of a parallel First Nations universe that becomes invisible when we return to our own (Valaskakis 1993) — and of the social structure that defines the Warlpiri world, including their media. For some reason, this realisation affects me deeply. Is it because of the extraordinary privilege extended to me by this community, allowing me access to their world? Or is it the level of trust shown in sharing knowledge that I seek? Regardless, it strengthens my resolve to complete this project. It's another moment that helps to confirm why this research is important.

Derek is dozing in the passenger's seat. Our 'Troopie' rumbles across lines of rolling sand dunes as we head towards the South Australian border.

Logo for the APY Lands

The changes in the country are noticeable the moment we turn off the Lasseter Highway about 100 km east of Yulara (near Uluru) — brown corrugations change quickly to red sand and then to hard-packed clay with accompanying vegetation changes. Across a flat sandy plain into a salt pan and into a drift of fine orange ochre dust. Bouldered hills and escarpments emerge from the low scrub. The hills are higher as we approach Pukutja-Eagle Bore but the only guidance are signs scrawled on abandoned car bonnets — Ford Falcons. Maybe they were written decades ago, preserved in this dry environment. One sign proclaims 'Ernabella Sports Weekend' with an arrow still pointing, long after the event has come and gone. Maybe it's always been there. Tracks to outstations peal away from the main road on either side and disappear into the scrub. The road winds through a valley ringed with steep-sided red ochre coloured hills pockmarked with clumps of spinifex and granite tors. The Mitchell grass flourishes were rain has recently fallen but it's mostly a tinder dry dull grey colour — a reminder of the harshness of this environment. Then we reach bitumen — a sinuous black strip which seems entirely out of place. Pukutja? But there are no signs. And not a single vehicle in four hours. We cross a treeless plain, the flatness stretching into my imagination. A line of hills hovers in a mirage above the horizon. Mesmerising. A huge flock of galahs rises from the open plain beside the road, settling in some dead trees as we thunder south. The road goes on and still there are no signs. I'm using a dated road map and navigating on instinct each time we reach an intersection — following the path most travelled seems to be the best choice. Abandoned car bodies by the roadside increase in frequency as we pass Indigenous communities I know are there — from the map — but they remain invisible. Abandoned and rusting Ford Falcons still seem to be the car of choice, stripped of anything remotely re-usable/recyclable. There's the occasional abandoned 'Troopie'. We miss the turnoff to Umuwa and make a 20 km detour before our instincts kick in — we've travelled about 300 km so we must be close. We turn around in the slippery red mud, the road waterlogged following a recent thunderstorm — and then we see 'Umuwa' scrawled in white paint across an old tractor tyre, half-buried in the sand by the side of the road, facing away from the direction we had just travelled.

We are here because the APY communities and their media have arguably played as important a role in shaping remote Indigenous communication as Yuendumu. Nearby Pukutja (formerly known as Ernabella) experimented with pirate community television in the late 1970s-early 1980s at the same time as Yuendumu, but received far less attention (Rennie and Featherstone, 2009). Community media production and technologies have advanced significantly since those pioneering early days but many people still call their local community television channel 'EVTV'. We are visiting at a sensitive moment — the announcement of a National Indigenous Television service is imminent but how it will impact on local communities remains unknown. It is our last planned remote community visit in an audience study that has seen us cross-cross the continent several times and drive upwards of 5000 km.

The APY Lands Cultural Festival, Umuwa, 2006

And like all of the other festivals we have attended, the APY Annual event is an ideal opportunity to speak to listeners and viewers — the audience. Some have gathered here from remote communities as far as 500 km away. It crosses my mind that my very first field trip to the Torres Strait, 18 years ago almost to the day, was to a festival. And for the very same reason. We spend three days talking to whoever is willing to speak to us, mediated through our local research assistant — someone who everyone knows and trusts. Most of the remote community people are too shy to give us more than a sentence or two but we are getting a very strong message about the importance of local television here. We are standing by the roadside as a long line of four-wheel drive vehicles files into a makeshift carpark when a lively middle-aged Anangu woman winds down the window and hails us from the passenger's seat: ‘Are you those fellas who doing this research about our media? I've got something to say to you!’

As we walk apprehensively towards her, all of the criticism of insensitive researchers visiting Indigenous communities come flooding back to me and I wonder if I am in for a dressing-down. She asks her driver to switch off the engine and introduces herself as a Pitjantjatjara woman, Mandatjara Isobel Wilson:

'I heard that national people from national capitals, they want to take away that culture from the land. EVTV, that's for the Pitjantjatjara people in the lands and we don't want to lose this one. This is our culture and we are teaching our children and we know that they've got a different culture. Northern Territory got a different culture. In New South Wales they've got a different culture. Here, in the Pitjantjatjara lands, we got a lot of children here. We are teaching our children. That's why we fight for land rights and we've been given that land rights back because we've been teaching the children to dance, to sing and keep our culture going. We don't want to give our culture to someone else to run this one. This is the Pitjantjatjara lands and Pitjantjatjara people are holding their own culture here. We want this one to keep going. We don't want to lose it. I'm talking strongly because this is the land and this is the culture of the Pitjantjatjara people. We started EVTV long time ago, really long time ago… This is our TV, this is our children's and we don't want people to run this one. Pitjantjatjara school and Yankunytjatjara schoolchildren they go to the college in Adelaide and they're learning about a different, different, different TV. And they're looking at what's happening to whitefellas on the other side of the world in that TV. That's no good for them children, that's really no good, you know. We want to have our children to learn from our culture and I'm supporting this one for children not for old people, that's for young people. And when we die, the young people know that; they can feel it; they can say, 'Oh my grandmother, Oh my father, he bin run this one. I can do that too!' We are showing the children that. Thank you very much, that's all I'm going to say to you.'

Her impassioned statement seems to sum up the policy failures being devised in Canberra at that very moment — a policy decision that will see ICTV displaced by the new National Indigenous Television, NITV, in 12 months' time (Gosford, 2007).

The brief meeting with Mandjatjara on the edge of the Great Victoria Desert was another defining moment in my research experience because her words echoed similar pleas from First Nations people around the world. The frustration in trying to facilitate change is expressed by all who work out in the communities. Just when one set of bureaucrats is educated and trained-up so they understand the issues involved and the context, they move on to other jobs — and a new person steps in, meaning that the process starts up all over again. The speed of personnel change in Canberra is described by some as like a spinning door, it happens so quickly (Featherstone, 2021). It is one reason why community voices are muted and policy change is infinitesimally slow. A senior government bureaucrat — who has spent many years at the highest levels in the Department of the Prime Minister — admitted that policymaking was more like Russian Roulette than a predictable process. She said that for significant policy change to occur, the 'stars would have to align'. Practically, it means that Indigenous media organisations must always be ready to present submissions or to make application for specialist project funds at the drop of a hat — when bureaucrats decide that the time is right: they set the agenda. It is a savage indictment on the processes of government but particularly cruel and insulting when it is extended to a sector of Australian society that struggles for its very existence.

The audience study of the Indigenous media sector was completed in 2007 and confirmed the central role being played by Indigenous radio and television across Australia, where they have been successfully incorporated into community social organisation. Where media are strongly linked to the local, audiences report that their media offer an essential service and play a central organising role in community life; they help to maintain social networks; play a strong educative role, particularly for young people; offer an alternative source of news and information; help to break down stereotypes and create opportunities for cross-cultural dialogue; and offer a crucial media for specialist music and dance (Meadows et al 2007). The evidence for these findings is compelling.

Indigenous media research cannot be separated from the context in which it exists — one of both covert and overt racism. Although some things have changed for First Nations people, with more opportunities for social advancement in many fields, it takes very little for the facade of equality to crack — racism is seldom far below the surface in Australia, at least. I have been aware of Indigenous inequities in Australia since I was a teenager, growing up in Brisbane. Manhattan Walk was a pedestrian mall on the south bank of the river and a common gathering place for the city's Indigenous population. Some of my earliest memories are of groups of Murris sitting together, socialising — and often drinking — as I walked into the city from South Brisbane Railway Station each day. It was long before a railway bridge was built across the river. It was a largely benign experience although occasionally someone would approach me and ask for 'two bob' [20 cents] for a pie. But I still recall vividly the moment that switched something on inside me. I was walking to the railway station in the early evening and noticed a Queensland Police department's 'Black Maria' prison van parked by the side of the road, outside one of the hotels along the riverbank. At that moment, an Aboriginal man stepped out of the hotel doorway and began walking along the footpath ahead of me. As he drew level with the police van, the doors were suddenly flung open and two burly officers grabbed him without a word, opened the doors of the paddy wagon and threw him into the cage, slamming the doors. I recall hearing the dull thud of his body hitting the inside of the van. I was stunned and felt a mixture of anger and fear. I had never witnessed such violence and it appeared to be entirely unprovoked. Not one was spoken during the altercation. The two officers glared at me before turning away and driving off with their prisoner. I stood there shaking in disbelief that human beings could treat each other this way. That incident of racist violence has framed my life as a journalist and researcher and it remains to this day a reminder of the injustices that shamefully continue to define Australia.

Do Indigenous media offer a counter to such attitudes? I believe they not only offer First Nations people a voice, but also offer the potential for building critical local self-esteem on a platform of cultural maintenance. The critical element here is that media production, in whatever form, is managed through existing community social structures — in the bush, this might entail a complex array of skin groups or clans while in urban settings, a similar level of ‘appropriate’ First Nations’ representation. In these ways, local media is ‘authorised’ and owned by the community. Indigenous control is the key. The absence of this structural base is arguably why the vast majority of government-sponsored projects designed to lift First Nations’ communities out of poverty over past decades have failed. Billions of dollars have been wasted because governments seem unable to listen — or to relinquish control.

One of the defining ideas that shaped both Songlines to Satellites and this account is the concept of the Dreaming and, in particular, Dreaming Tracks or Songlines. In Australian Indigenous cosmology, Dreaming Tracks describe journeys across the landscape by ancestral beings but they are also communication corridors — actual pathways travelled by people for tens of thousands of years (Michaels, 1985; 1986). And it's still happening: many of Australia's modern highways are built on traditional Aboriginal pathways — Dreaming Tracks — and it's only recently that researchers have become aware that some Indigenous people used star maps as an aid to remember navigational waypoints. They did not necessarily use the stars for navigation but used star patterns to remind them of navigational points on earth (Kerwin 2010, Fuller et al 2014) — more evidence of the intimate communication processes that are a defining characteristic of First Nations people.

So what then of the future? When I began my own research journey more than 30 years ago, I was confident that Indigenous ingenuity would always win. The pace may be glacial, but many advances have been made. Technological changes have enabled the most remote communities on the planet to speak out although with so much 'background noise', whether anyone is listening remains questionable. The opportunity to communicate remains strong and I am optimistic about a future for Indigenous communities but it remains a struggle. Little has ever been given to First Nations people with communities having to fight for every step forward. Recognition of Indigenous people in the Australian Constitution is an ongoing battle, as are attempts to formalise an Indigenous voice in Parliament. The so-called co-management model (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020) under discussion at the time of writing seems modest and achievable and yet, the federal government continues to obfuscate.

Since I began my research in this area in the late 1970s, the initial fears of cultural damage caused by uncontrolled television broadcasts, particularly to remote indigenous communities, has given way to a more measured perception of the empowering possibilities of new communication technologies — for example, the positive impact of television in supporting languages and cultures (evident in our 2007 national audience study) or of informing indigenous people of the survival of their counterparts across the world (as my Canadian sojourn revealed) (Meadows, 2001). This lived experience is evident in Australia’s remote multilingual Indigenous communities. One of the founders of the Central Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), Freda Glynn, describes seeing Arrernte people weeping when then first heard their own languages spoken on local radio in Central Australia in the early 1980s. And in a striking similarity, Mary Simon of the Nunavut Implementation Commission in 1994 described how her grandmother first heard other Inuit voices — from Greenland — on shortwave radio in Canada’s Arctic. It was then that she knew she was related to Inuit in other countries. Television for the Greenland Inuit meant they could identify with the rest of the world. They saw the role of the media — and control of it — as so important as to be the first area of jurisdiction they took control of following the granting of home rule to the island in 1979. Programmers and audiences for the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) in Canada have discovered that subtitles are no longer needed because the ears of communities across the North have quickly become attuned to each other's dialects (Stenbaek 1992, p. 59-61). Culture — a whole process of living — is constantly evolving and appropriation of technologies like the Internet and mobile telephony have offered powerful tools for First Nations people to challenge the dominant ideology through the formation and operation of an Indigenous public sphere (Avison and Meadows, 2000).

In both Australia and Canada there is still much to be done in recognising indigenous broadcasting access rights in terms of prior ownership and the subsequent effects of dispossession. But despite the infinitesimal policy movement in such areas, First Nations people from both countries have demonstrated the empowering possibilities offered by new communication technologies. A diversity of culturally appropriate media forms has emerged and will continue to emerge as unique forms of cultural resource management (Mercer, 1989) — a response to imposed political and technological environments. If control of cultural production is in the hands of Indigenous people, then this represents a potentially powerful challenge to the dominant cultural hegemony of mass media and thus, mainstream society.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1999) Digital Dreaming: a national review of Indigenous media and communications, Executive Summary, Woden, ACT, March.

Avison, Shannon and Meadows, Michael (2000.) ‘Speaking and hearing: Aboriginal newspapers and the public sphere in Canada and Australia’, Canadian Journal of Communication 25: 347-366.

Commonwealth of Australia (2020), National Indigenous Australians Agency, Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Interim Report to the Australian Government, October. Available at https://voice.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-01/indigenous-voice-codesign-process-interim-report-2020.pdf

Featherstone, Daniel (2021) Personal communication, August.

Forde Susan, Foxwell Kerrie and Meadows Michael (2009) Developing Dialogues: Indigenous and Ethnic Community Broadcasting in Australia. London: Intellect; and Chicago: University of Chicago Press; see also Apple Books https://books.apple.com/au/book/developing-dialogues/id429569958.

Fuller, Robert S; Trudgett, Michelle; Norris, Ray P; and Anderson, Michael G (2014) Star maps and travelling to ceremonies — the Euahlayi people and their use of the night sky, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 17 (2), 1-16.

Gosford, Bob (2007) 'The lost opportunities of NITV', Crikey, 30 July, available at https://www.crikey.com.au/2007/07/30/the-lost-opportunities-of-nitv/

Kerwin, Dale (2010) Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways', Queensland Historical Atlas, 26 August, available at https://www.qhatlas.com.au/content/aboriginal-dreaming-paths-and-trading-ways

Meadows Michael (1988) The jewel in the crown: The coming of television to the Torres Strait could be as significant as the impact of religion there, 117 years ago, Australian Journalism Review 10(1&2): 162–169.

Meadows, Michael (1994) 'The way people want to talk: Indigenous media production in Australia and Canada', Media Information Australia 73, pp. 64-73.

Meadows, Michael (2001) Voices in the Wilderness: Indigenous Australians and the News Media. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Meadows, Michael, Susan Forde, Jacqui Ewart and Kerrie Foxwell (2007) Community Media Matters: an audience study of the Australian community broadcasting sector. Brisbane: Griffith University. Available at https://www.cbaa.org.au/article/community-media-matters

Mercer, Colin (1989) Antonio Gramsci: E-Laborare, or the Work and Government of Culture, Paper delivered at TASA conference, La Trobe University, Melbourne, December

Michaels Eric (1985) Constraints on knowledge in an economy of oral information, Current Anthropology, 26(4): 505–510.

Michaels, Eric (1986) Aboriginal Invention of Television Central Australia 1982–1985, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Molnar, Helen and Meadows, Michael (2001) Songlines to Satellites: Indigenous Communication in Australia, the South Pacific and Canada, Sydney, Pluto Press.

Rennie, Ellie and Featherstone, Daniel (2009) ' “The potential diversity of things we call TV”: Indigenous community television, self-determination and NITV', Media International Australia 129, November, 52-66.

Schnukal, Anna, 1987, Torres Strait Creole: historical perspectives and new directions, Conference notes, University of Queensland.

Stenbaek, Marianne A. (1992) ‘Mass Media in Greenland: The Politics of Survival’, in S. Riggins (ed) Ethnic Minority Media: An International Perspective, Newbury Park, Sage, 44-62.

Valaskakis, Gail Guthrie (1993) 'Parallel voices:L Indians and others — narratives of cultural struggle', Canadian Journal of Communication 18:3, 283-296.